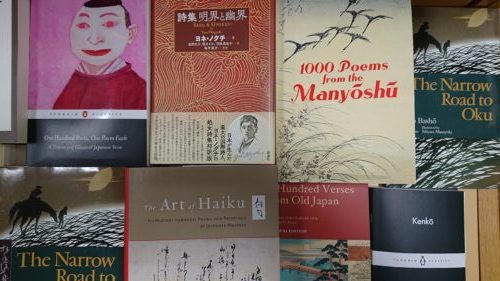

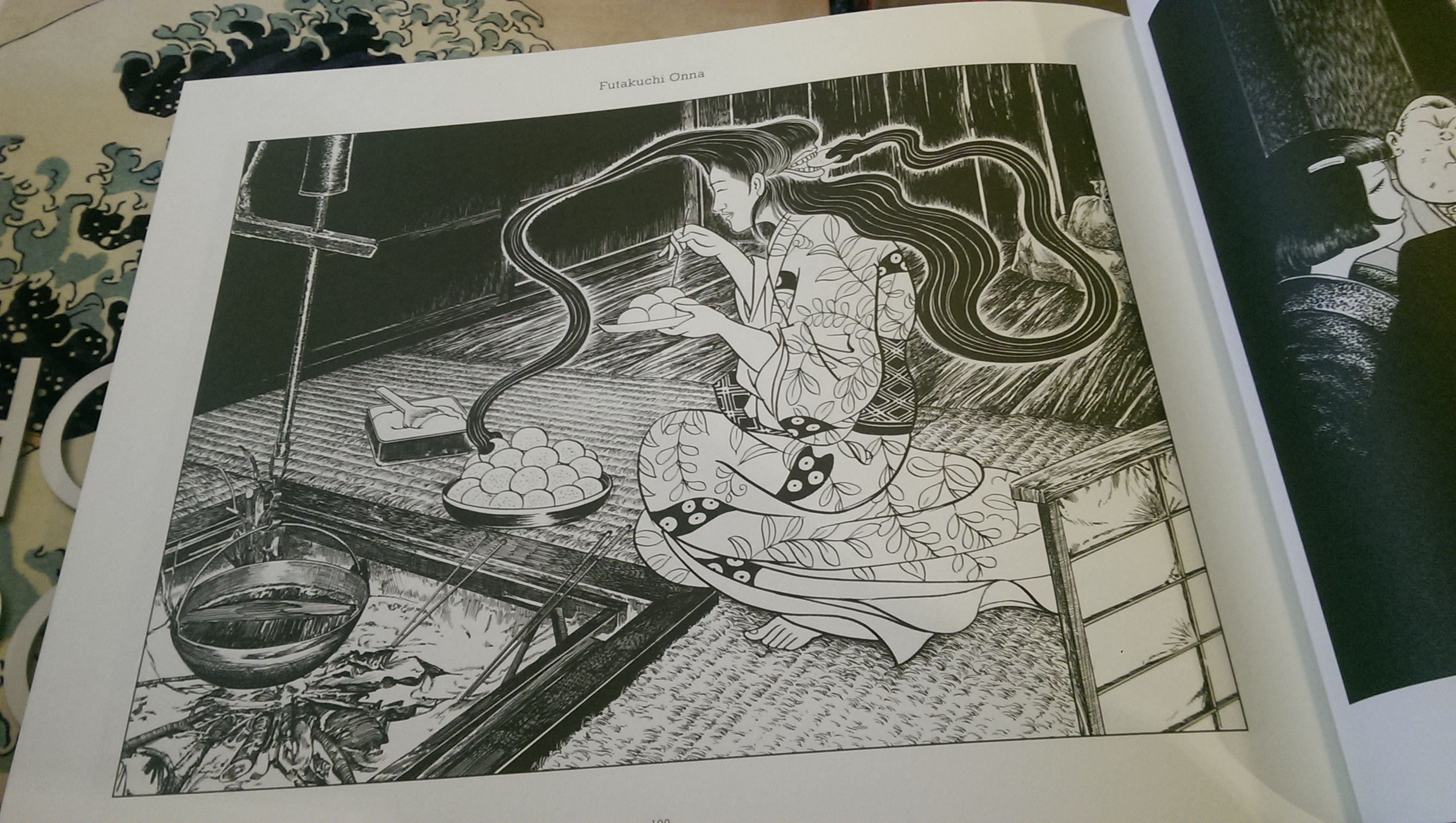

Futaguchi Onna, two-mouthed woman, a Japanese monster from folklore, from Shigeru Mizuki’s illustrated directory of Yokai. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.

Futaguchi Onna, two-mouthed woman, a Japanese monster from folklore, from Shigeru Mizuki’s illustrated directory of Yokai. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.N

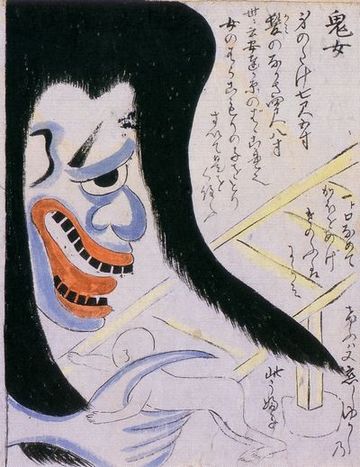

obody can escape childhood without some exposure to monsters, demons, witches, or trolls. Be they tales about the lovable ogre Shrek, the Devil, Harry Potter, Japanese Oni or games like Pokémon. A Kijo, an Oni (demon) woman or Japanese troll from the Edo Period (1603-1868) collection of ghost stories, Tosa Obake Zoshi. Image: Wikipedia

A Kijo, an Oni (demon) woman or Japanese troll from the Edo Period (1603-1868) collection of ghost stories, Tosa Obake Zoshi. Image: WikipediaStories about isolated mountain dwelling Yama-Uba and Yamanba that can devour oxen, children, men and dozens of rice balls in one mouthful, and transform themselves back into their primal form (usually snakes, spiders, or badgers) have captivated and terrified people for generations.

These stories can be found throughout Japan as well as in the country’s art, theatre, literature and folk tales.

Extreme hunger is a familiar narrative that also runs through folk tales from other cultures including the Grimm’s Fairy Tales like Hansel and Gretel and the rather disturbing tale The Juniper Tree.

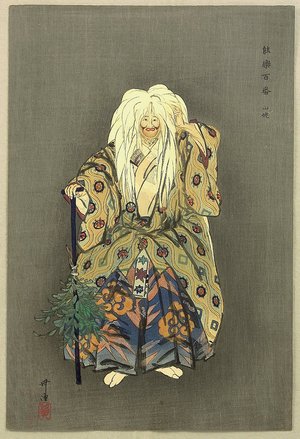

Yama-Uba by Kogyo Tsukioka (1869-1927) from series One Hundred Noh Plays. Image: Public Domain.

Yama-Uba by Kogyo Tsukioka (1869-1927) from series One Hundred Noh Plays. Image: Public Domain.In public she is young, beautiful, hardworking and gracious, but he later discovers that in private (when she is hidden and alone) she binges on food, and has a huge hidden second mouth on the top of her head. Once discovered, her true terrifyingly unattractive identity as either an animal, old hag or demon, is dramatically revealed.

A translation of this tale by Roger Pulvers is included in the award-winning illustrated collection of classic Japanese fairy tales Once Upon a Time in Japan.

Other versions of the Yama-Uba story are simpler and involve travellers being attacked and livestock being devoured whole. Others depict evil mountain crones with unkempt white hair and scarecrow-like kimonos sneaking into homes and gobbling up children.

However, not all of them feature cannibalism. On occasion, they portray benign and even nurturing characters, as in the story of the Yama-Uba who raises Kintaro, the Golden Boy with super-human strength.

Understandably, there has been much analysis over the origin and meaning of these stories, which often mirror the perspective and fears of those deconstructing them.

T

he current longevity of the Japanese people and its rapidly ageing population are very well documented. But when resources were scarce long before urbanisation, the old, unwell and mentally ill were sometimes banished into the mountains.There is a famous legend known as Ubasute in which the old were carried into the mountains at a certain age and abandoned in an ancient form of euthanasia.

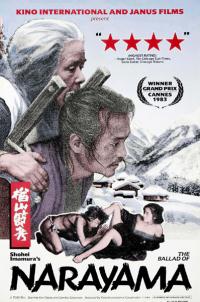

The drama and trauma of this is strikingly captured in the prize-wining novel, The Ballad of Narayama by Shichiro Fukazawa (1914-1987), which has been turned into at least two film adaptations; one of which won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival in 1983.

Poster for The Ballad of Narayama (1983 film) 1983. ©1983 Toei Company

Poster for The Ballad of Narayama (1983 film) 1983. ©1983 Toei CompanyHe says his novel Dendera, published in English translation in 2015, is “the amalgamation of my own personality with the legend of Ubasute — leaving the elderly to die of exposure — with the snowy mountain as the backdrop”.

A more recent manifestation of something akin to these tales is Aokigahara, otherwise known as Japan’s Suicide Forest. Located near Mount Fuji, this is a sad location where more than 200 hundred people are said to have gone to kill themselves.

Ancient Japanese tales about women and food are generally not happy ones and are not limited to Yama-Uba storiesAncient Japanese tales about women and food are generally not happy ones and are not limited to the Yama-Uba and Ubasute stories. Uke-Mochi, the Japanese goddess of food, is a perfect example.

According to legend, she spewed out game from her mouth when facing the land; and fish when facing the ocean. But when welcoming her brother, the storm-god, with a specially prepared feast, he wasn’t too pleased with his banquet of sisterly vomit and abruptly killed her.

According to the myth, her dead body subsequently produced rice, beans and millet, while her head produced an ox.

M

any consider eating disorders such as bulimia and anorexia as modern culture-bound Western illnesses that wouldn’t have afflicted individuals in ancient times in Japan or anywhere else. Interestingly, the word bulimia derives from the Greek word for ravenous hunger (bous –ox and limos – hunger) and is defined as “a serious eating disorder that occurs chiefly in females, and is characterized by compulsive overeating usually followed by self-induced vomiting”.

Anorexia, on the other hand, is from the Greek words: negation and appetite.

It was first officially defined as a medical term in 1873 by the personal physician of Queen Victoria, who had nine children including five daughters, and wasn’t renowned for her parenting skills. These illnesses with their modern and established definitions are now on the rise both in Japan and the rest of the world. While the world has fallen in love with Japanese food, and newspapers report on Japan having the healthiest diets, anthropologists, sociologists, feminists and psychologists are starting to research eating habits in Japan.

Food nourishes and sustains. It is essential for our physical and mental development. It transforms us but without it development can be delayed. Human psyche and emotions run very deep and influence all of our eating habits. Some argue that a desire to remain young is often the force behind these illnesses.

There are also experts that believe some young girls have a deep-rooted fear that reaching maturity will lead to them becoming like their mothers and that this can be avoided or postponed by not eating. Others that it is a symptom of being marginalized, narcissistic, or disenfranchised – combined with the constant media portrayal of beautiful people and the inference that the perfect body and marriage will bring happiness.

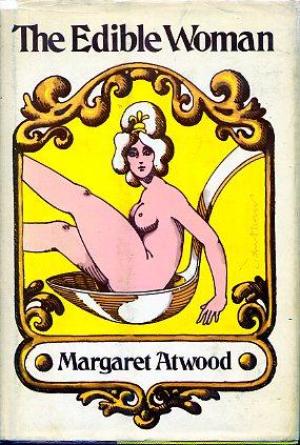

Cover of the First American Edition (1969) of The Edible Woman by Margaret Atwood.

Cover of the First American Edition (1969) of The Edible Woman by Margaret Atwood.Food is and has always been a potent symbol and motif deployed in storytelling in many languages, sometimes to make a radical point or challenge the status quo – and not exclusively in Japan. Margaret Atwood’s novel The Edible Woman is a particularly good example of this.

The Japanese expression Yamanba has recently been used to describe a certain alternative look that some young Japanese girls (known as Gyaru or Kogal) first adopted in the 1990s. The look initially involved dyed blond hair, dark facial tans and extensive white above eye makeup.

Gyaru Sone, whose real name is Natsuko Sone, has sprung to fame and become a reasonably well-known and popular media celebrity by capturing the nation’s imagination with her look, attitude and appetite. Besides having a similar type of look, she has also won numerous competitive eating competitions in Japan and abroad; and has the dubious honour of having been crowned Gluttonous Queen of Hawaii.

M

odern forms of Oni pop up everywhere. Nowadays they can be sexy and cute, and even wear short skirts. But thanks to urbanisation, you’re unlikely to find any Oni if you venture into the woods or mountains at night. But they are thriving in different forms in manga, anime or digital games.  Pokémon series character Jynx. The character’s facial colour was modified from black following criticism. Image: Wikipedia.

Pokémon series character Jynx. The character’s facial colour was modified from black following criticism. Image: Wikipedia.This said, the real demonic trolls of our time are Internet Trolls. From their private hidden spaces, in their real form (probably while snacking or constantly grazing to use the latest terminology), they spit their spiteful venom and vent their spleen with the rage of ogres by writing anonymously, and verbally assaulting all around them.

A much more intelligent and considered commentary on the ills of Japanese society, however, can be found within novella and contemporary fiction. Self-destructive narratives with similar motifs of the past, of being dislocated and disenfranchised, appear in some of Japan’s best contemporary literature written by its many award-winning writers. Nowadays novels can be written from the perspective of the Oni, be it a Yama-Uba or another type, who still represent society’s darkest fears, but are often portrayed as lonesome disenfranchised individuals seeking meaning and companionship in frenetic urbanised Japan.

While mountain woods may no longer be de rigueur for today’s Oni, modern image-conscious ‘creatures’ can certainly be found in the urban sprawl, living on the margins of society, overeating, dressed in unconventional attire, and perhaps occasionally self-harming.

Unsurprisingly, such characters can be found in bestselling novels written by the current cohort of brilliant Japanese female authors like Mari Akasaka’s Vibrator about a bulimic young alcoholic journalist; as well as Innocent World by Ami Sakurai and Hitomi Kanehara’s award-winning Snakes and Earings.

© Red Circle Authors Limited

Tokyo Tower at Night from Ropponji 東京タワー(六本木ヒルズより)Kakidai (Wikimedia)

Tokyo Tower at Night from Ropponji 東京タワー(六本木ヒルズより)Kakidai (Wikimedia)