Japanese Yakuza ‘peacocking’ at a festival in Tokyo in May 2007. Photograph: Jorge from Tokyo, Japan/Wikipedia.

Japanese Yakuza ‘peacocking’ at a festival in Tokyo in May 2007. Photograph: Jorge from Tokyo, Japan/Wikipedia.E

veryone seems to want a tattoo these days. The numbers are staggering: More than a third of people between the ages of eighteen and thirty in the United States and Britain now have tattoos, and the number is expected to keep on growing. It is not just the young, celebrities, sportsmen and women, but also society’s ‘civilized elite’ that are adorning, decorating and branding their bodies with tattoos. Tattoos are everywhere: on the arms of royalty; on television; on the ankles of politicians’ wives; on the Internet and book covers. No serious crime fiction fan could have missed the international bestselling book: The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo, for instance. However, The King With the Japanese Dragon Tattoo and the impact the craft and Japan’s artisans have had around the world and on Japanese literature, are much less well known.

Image from: A journal of a voyage to the South Seas by Sydney Parkinson, London, 1784. Probably sketched in 1769. Parkinson was the artist on Captain Cook’s 1st voyage to New Zealand in 1769. Source: Wikipedia.

Image from: A journal of a voyage to the South Seas by Sydney Parkinson, London, 1784. Probably sketched in 1769. Parkinson was the artist on Captain Cook’s 1st voyage to New Zealand in 1769. Source: Wikipedia.The term comes from ta-tau (to strike or mark) in Polynesian languages. Its use spread with the publication of Cook’s adventures in 1769, which included detailed observations and records of the ‘tattooed savages’ that the adventurer and his team encountered. However, the practice is, in fact, far older in Europe and elsewhere.

The world’s oldest known tattoos are said to be the sixty that were discovered on the mummified body of Iceman Otzi, found in an Italian glacier in 1991. Otzi apparently died around 3250 BC. Tattoos have been also found on mummies in China, Chile, Egypt, and the Philippines. The practice is also very old in Japan, with a similarly long pedigree and illustrious past.

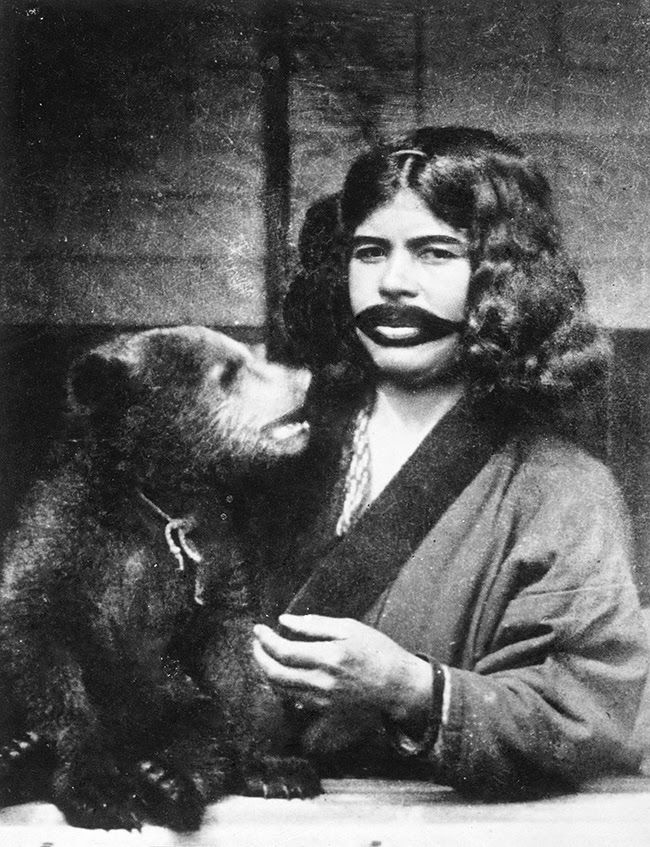

An Ainu woman shows her facial tattoos while holding a live bear on her lap, 1922. Image: Wikipedia.

An Ainu woman shows her facial tattoos while holding a live bear on her lap, 1922. Image: Wikipedia.Tattoo art grew in parallel with the development and popularity of Japanese woodblock printing (ukiyo-e). Similar techniques and motifs were used as well as Nara ink, a black soot-based ink that turns greenish blue after being inserted under the skin.

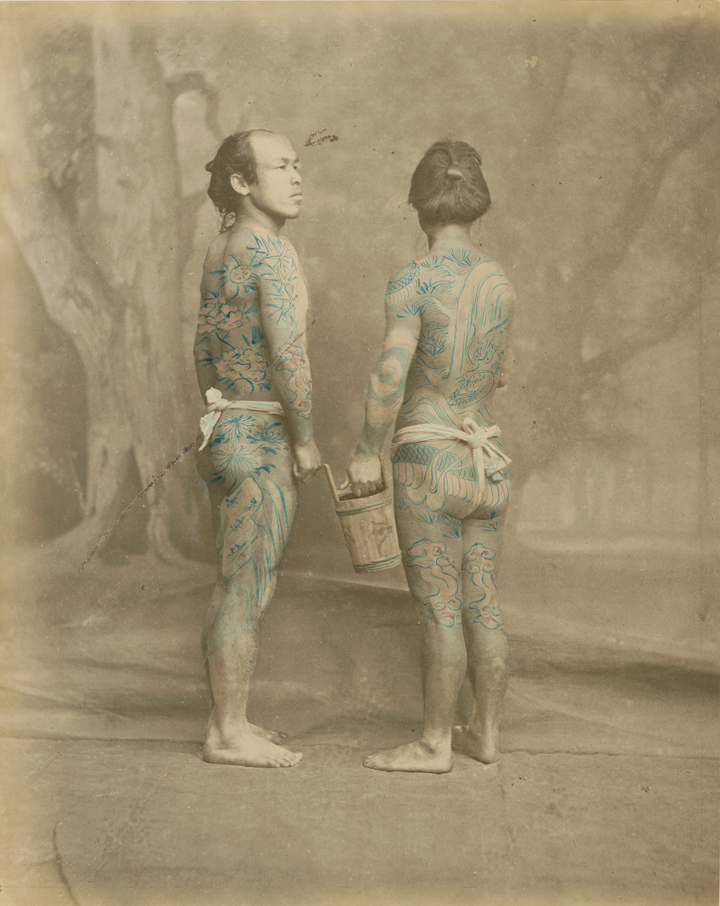

An early example of irezumi (tattoos) from 1870s. From Felice Beato in Japan. Source: Wikipedia.

An early example of irezumi (tattoos) from 1870s. From Felice Beato in Japan. Source: Wikipedia.During this period, rough confident men who worked semi-naked in loincloths, such as firemen and carpenters, proudly wore tattoos in a style of decorative permanent attire.

L

ike many other iconic Japanese cultural exports, including woodblock printing, this craft received more respect and acknowledgement as an art form outside Japan than from inside the country. In 1881, the future British monarch, Prince George (1865-1936), visited Japan while serving in the British Navy; and like many others before him (to his mother’s great disapproval) got a Japanese tattoo.

His blue and red dragon on his forearm was never seen in public, but he did reportedly show it to the Meiji Emperor (1852-1912).

Just like celebrity endorsements or a Royal Warrant of today, this increased awareness and the prestige of Japanese tattoos massively outside Japan.

Just like celebrity endorsements or a Royal Warrant of today, this increased awareness and the prestige of Japanese tattoos massively outside Japan. Despite this, they were still technically illegal in Japan, having been prohibited in 1872, when the sixteen year-old prince got inked.

Woman getting a tattoo probably of her lover’s name. Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892). Source: Wikipedia.

Woman getting a tattoo probably of her lover’s name. Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892). Source: Wikipedia.This isn’t the case with irezumi, horimono (another Japanese word used to describe tattoos), and tatou, a loanword that really needs no explanation but is in fact used to describe Western-style tattoos in Japanese.

Yet the nation still hasn’t come to accept tattoos quite as readily as many other countries have. Government officials have tried to ban workers from having them; gyms, spas, and swimming pools ban people with them or insist on them being concealed; and the Japanese Tourist Agency is struggling with policy and rules related to the growing number of tattooed tourists visiting the country.

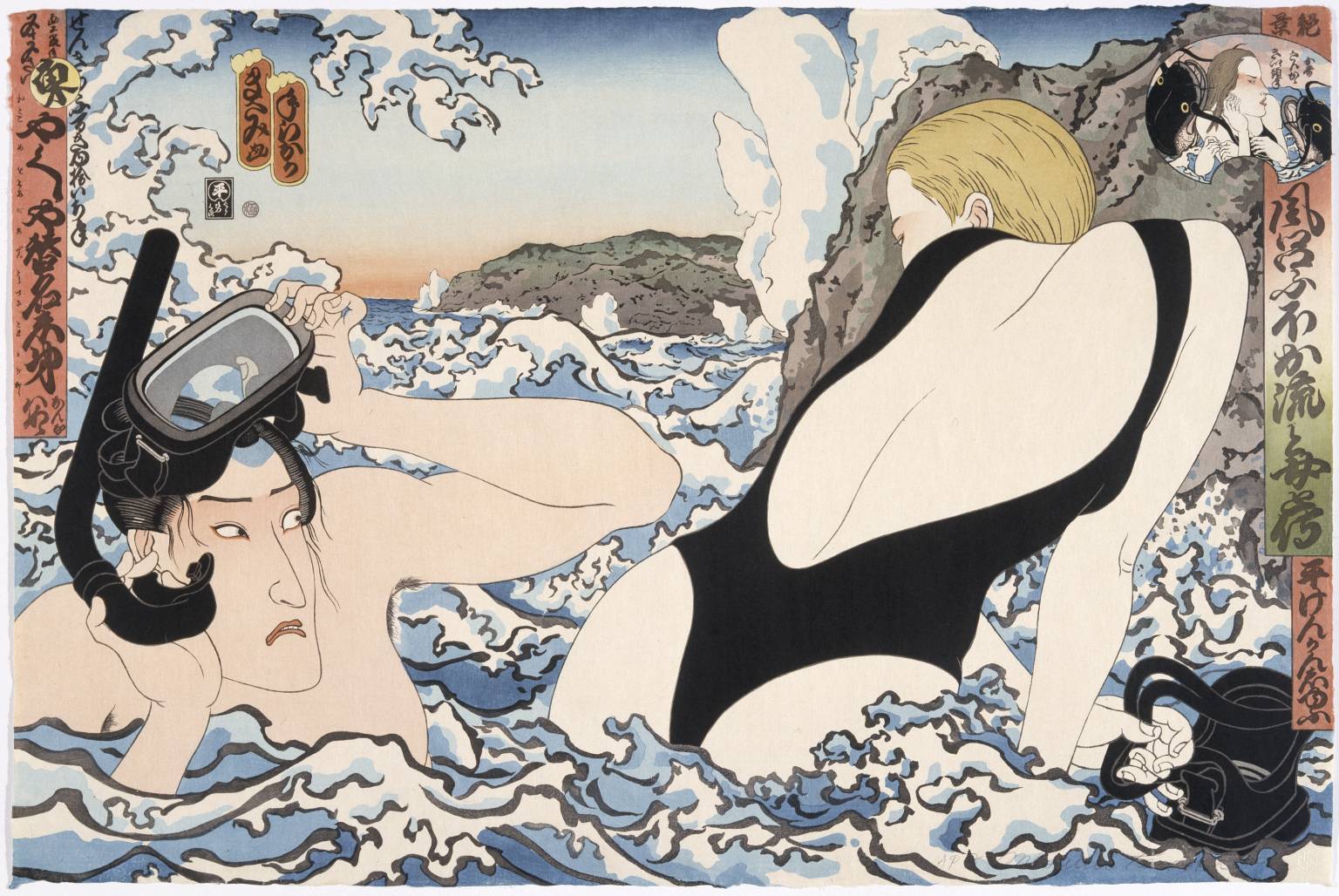

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892) Woodcuts from Japan in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Source: Wikipedia.

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892) Woodcuts from Japan in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Source: Wikipedia.Their association with penal establishments, prohibition, gangsters, antisocial behavior, criminality, the underclass, and certain lower class professions, has meant that ever since the Edo Period, tattoos have been hidden from public view.

They have been treated like invisible kimono underwear and only revealed when it is appropriate, and to create maximum impact.

Impulse-driven casual tattooing is still unusual in Japan, as is marking one’s body to commemorate, often when drunk, shared social events.

Appointments are required and a proper traditional Japanese tattoo will be seen as a major endeavor; as well as a time consuming and significant financial investment. One that is carried out with serious intent and rarely on a whim.

A full-body tattoo can take years and cost tens of thousands. They can be life changing either intentionally or unintentionally.

T

at-Lit doesn’t exist yet as an international publishing genre, but the popularity and fascination with tattoos is not new: Winston Churchill (1874-1965) had one. And tattoos have, of course, featured prominently in many book genres; spanning adventure, crime, science fiction and mystery. Some of the world’s leading international authors and most famous books have used tattoos, or tattooed individuals as important narrative devices.

Some of the world’s leading international authors and most famous books have used tattoos, or tattooed individuals as important narrative devices.These include: Moby-Dick (1851) by Herman Melville (1819-1891); Treasure Island (1883) by Robert Louis Stevenson (1850-1894), The Red-Headed League (1891) by Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930), The Illustrated Man (1951) by Ray Bradbury (1920-2012), Skin (1953) by Ronald Dahl (1916-1990), and Papillon (1969) by Henri Charriere (1906-1973) to name just a few.

Ronald Dahl’s short story is a brilliant example. Set in Paris, a man has a picture of a beautiful woman painted on his back by a famous artist and then tattooed for preservation.

Many years later it is auctioned off in an art gallery for a significant sum with much debate on how the ‘human canvas’ can be managed and exhibited.

Cover of collection of short stories by Ronald Dahl published in 2000. The title story Skin was originally published in The New Yorker in May 1952.

Cover of collection of short stories by Ronald Dahl published in 2000. The title story Skin was originally published in The New Yorker in May 1952.The story’s plot twists and black humor are even more macabre when you consider that there are actually museums in Japan with collections of persevered human tattooed skins.

And museums outside Japan are now recognizing traditional Japanese tattoos for their artistic value and are arranging installations and exhibitions: albeit rather differently. The travelling international exhibition: Perseverance: Japanese Tattoo Tradition in a Modern World is one such show.

Specialist websites where tattoo ideas and templates can be accessed, photo-sharing apps and reality televisions programs such as: Miami Ink, LA Ink, Ink Masters, America’s Worst Tattoos and Britain’s Tattoo Fixers, have exposed the world of tattooing to a mass-market helping to amplify interest and demand.

The morphing of Japanese anime and manga imagery with traditional Japanese tattoo techniques and designs has broadened appeal and created new terms such as Otattoos (otaku-tattoos/geek-tatts).

Anime based and inspired tattoos. Image: Spoon & Tamago.

Anime based and inspired tattoos. Image: Spoon & Tamago.Specialist tattoo travel firms now arrange trips to Japan for individuals that wish to copy Prince George and decorate their bodies with Japanese art – modern or traditional.

J

apanese authors and publishers can’t ignore them either; especially as Junichiro Tanizaki (1886-1965), one of Japan’s best and most highly respected modern authors came to fame with a debut novella titled: The Tattooer (1910) – also known as Shisei -which he wrote at the age twenty four. In the story a tattoo artist, obsessed with finding the perfect women to tattoo, drugs a young woman and tattoos a black spider onto her back.

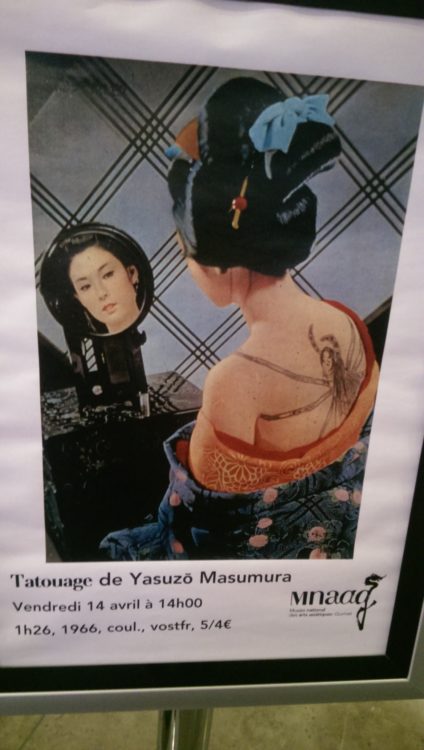

Poster advertising a screening of the 1966 film Irezumi directed by Yasuzo Masumura (1924-1986) in Paris 2017. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.

Poster advertising a screening of the 1966 film Irezumi directed by Yasuzo Masumura (1924-1986) in Paris 2017. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.Anthropologists, socialists and Japanologists have different views on why people get tattoos. Social branding, shared peer-experiences, and fashion are widely thought to be behind most people’s decisions.

The Guinness Book of Records lists the oldest man getting his first tattoo as a 104-year-old British man who had his nickname and date of birth tattooed – Jake 6.4.1912 – on his birthday to raise money for charity with his grandson.

It would no doubt have been a special form of bonding and experience sharing. Nevertheless, tattoos as simple fashion statements or designer accessories to be displayed, is a relatively new concept in Japan.

Traditionally, in Japan, tattoos have generally been done as some form of: initiation and induction; communal membership; for protection; talisman or to affect transformation.Traditionally, in Japan, tattoos have generally been done as some form of; initiation and induction; communal membership; for protection; talisman or to affect transformation.

The bestselling American author Dan Brown understands the narrative and consequences tattoos can have when he writes in The Lost Symbol: ‘the act of tattooing one’s skin was a transformative declaration of power, an announcement to the world: I am in control of my own flesh.’

Nevertheless, everyone has his or her own particular reason. The American actor, Johnny Depp, for instance, is on record as saying: ‘My body is my journal, and my tattoos are my story’.

D

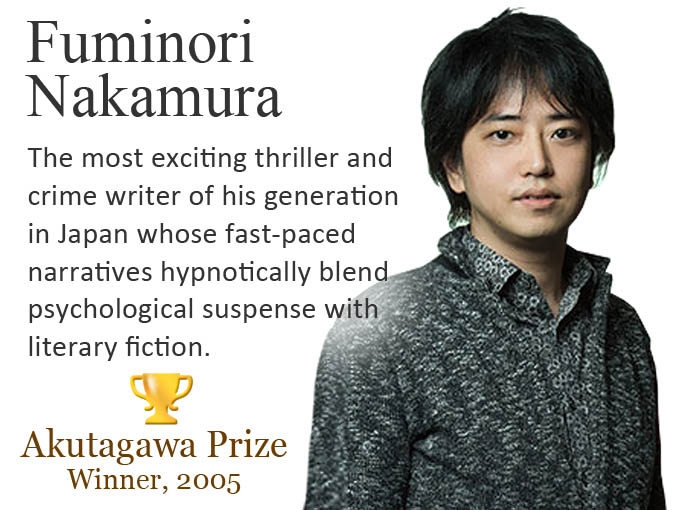

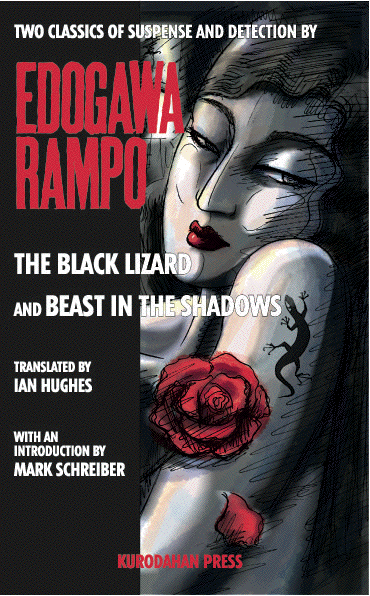

espite Japan’s ambivalent attitude towards tattoos Japanese authors are conscious of how the motif has been used successfully in the past. Some decorate their stories and narratives with them. They are used as plot devices to help solve crimes; to develop and describe marginalised characters; and depict changing power dynamics in relationships.  Cover of 2006 edition, published by Kurodahan Press, containing two translations into English of short stories by Ranpo Edogawa including The Black Lizard.

Cover of 2006 edition, published by Kurodahan Press, containing two translations into English of short stories by Ranpo Edogawa including The Black Lizard.Two Japanese novels that follow the tattoo crime fiction tradition that Arthur Conan Doyle helped establish are: The Black Lizard and the Beast in the Shadows (1934) by Ranpo Edogawa (1894-1965), who pioneered crime fiction in Japan; and The Tattoo Murder Case (1948) by Akimitsu Takagi (1920-1995).

One of Japan’s best known authors, Yukio Mishima (1925-1970), had a cameo role in the 1968 film adaptation of The Black Lizard, which features a master thief with a lizard tattoo on her shoulder.

Cover of English translation edition of The Tattoo Murder Case by Akimitsu Takagi which was originally published in Japanese 1948.

Cover of English translation edition of The Tattoo Murder Case by Akimitsu Takagi which was originally published in Japanese 1948.Seishi Yokomizu (1902-1981) another highly successful author of detective novels and historical fiction, who like Edogawa, has a literary-prize named after him, also uses tattoos as a narrative device in his books.

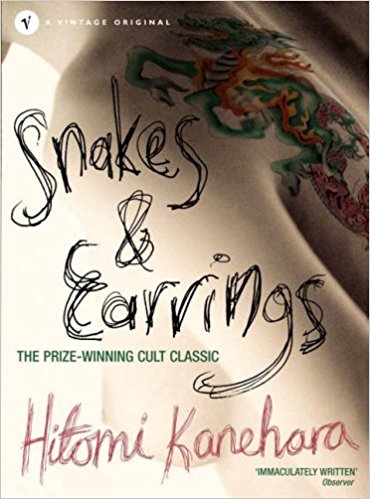

Cover of Hitomi Kanehara’s book published in 2003. It was adapted and released as a film in 2007, directed by Yukio Ninagawa (1935-2016), best known for his Japanese language productions of Shakespeare plays and Greek tragedies. Image: Amazon.

Cover of Hitomi Kanehara’s book published in 2003. It was adapted and released as a film in 2007, directed by Yukio Ninagawa (1935-2016), best known for his Japanese language productions of Shakespeare plays and Greek tragedies. Image: Amazon.The Paradise Bird Tattoo (or, Attempted Double-Suicide) by Choukitsu Kurumatani (1945-2015) is another example. It depicts the polarized extremes of boredom and the grittiness of life on the margins of Japanese society in 1970s Osaka.

A more recent, award-winning, example is Hitomi Kanehara’s bestselling debut novel Snakes and Earings (2003), which describes a possessive murderous relationship with a tattoo artist.

N

on-Japanese authors have also picked up on the possibilities. The Concubine’s Tattoo by Laura Joh Rowland (2000) and the Booker Prize short-listed title: The Garden of Evening Mist by Twan Eng (2012) being just two examples. The latter manages to combine a serene Japanese garden in Malaysia, a traditional Japanese tattoo, failing memory, looted treasure and a Japanese wartime internment camp in one book.

Traditional Japanese tattoos often include images of animals, mystical creatures, demons and Buddhist deities, but unlike Japan’s famous Zen gardens and temples, they do not exude simple tranquil understated beauty.

The influence of Japanese Zen Buddhism is, of course, widely acknowledged. Apple’s Steve Jobs, for example, was a fan and is said to have been impressed with Zen’s simplicity, clarity and impact on Japanese design.

The book, Zen and the Art of Archery (1953), by the German philosopher Eugene Herrigel (1884-1955), is said to have introduced the concept of Zen into the European zeitgeist. It triggered hundreds of books with similar titles including the 1970s classic Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. Japanese tattoos with their own form of sophistication also have global reach and impact, but share little in aesthetic sense with Zen.

Nevertheless, some are determined to make the link and compare horishi, Japanese tattooers, and their craft to that of Zen masters. They argue that getting a tattoo in Japan is a Zen-like transformational experience that encompasses dedication, pain management, repetition, routine, silence, controlled breathing and concentration on nothingness.

In sharp contrast, outside Japan having the Japanese character depicting the word Zen or the Enso symbol associated with it (an incomplete circle) tattooed onto one’s body is considered trendy. It can be done quickly on the spur of the moment, but brings only fleeting enlightenment.

Cover of Writing from the Zen Masters, Penguin Books – Great Ideas, depicting the Enso image on the cover. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.

Cover of Writing from the Zen Masters, Penguin Books – Great Ideas, depicting the Enso image on the cover. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.You may, in the first instance, prefer to pick up one of the many brilliant Japanese novels where tattoos are featured. Not only will you get under the skin of Japan, you may learn about the art form, and the impact it can have.

Admittedly, you won’t be permanently inked, but Japan’s talented and creative authors will leave a lasting impression that could be just as transformational.

© Red Circle Authors Limited

Traditionelle Tätowierung mit Tebori Photo: Diana Kohrs (Wikimedia)

Traditionelle Tätowierung mit Tebori Photo: Diana Kohrs (Wikimedia)