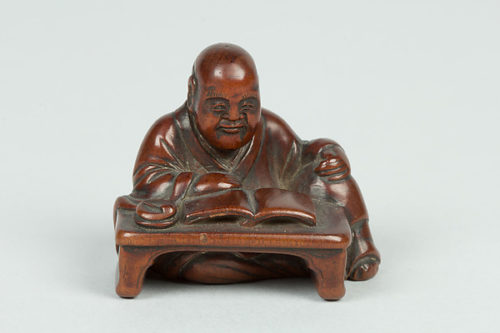

19th century wood Netsuke, a carved button-like traditional Japanese kimono accessory. Gift of Mrs. Russell Sage, 1910 , to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Dimensions: H. 1 3/8 in. (3.5 cm); W. 1 1/4 in. (3.2 cm). Image: Pubic Domain.

19th century wood Netsuke, a carved button-like traditional Japanese kimono accessory. Gift of Mrs. Russell Sage, 1910 , to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Dimensions: H. 1 3/8 in. (3.5 cm); W. 1 1/4 in. (3.2 cm). Image: Pubic Domain.S

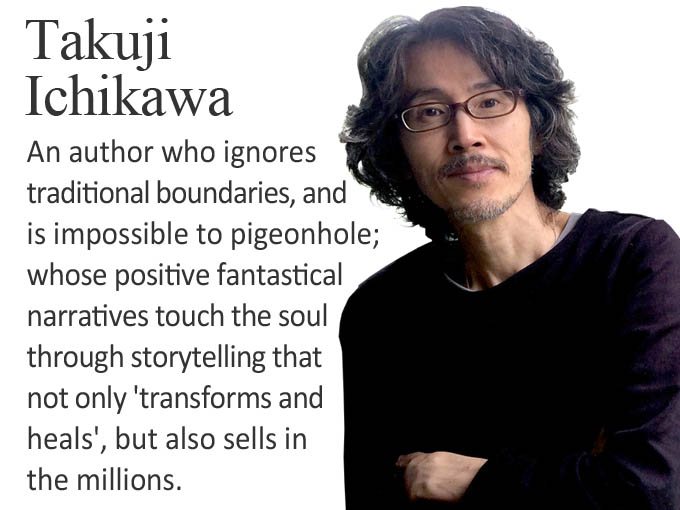

tripped back to the essentials; compact but still complete; intelligently and stylishly packaged with quality shining through: These are traits that have been applied to Japanese product design, art, architecture, and food since time immemorial. Interestingly, they are also the perfect terms to describe the nation’s creative writing, especially works by its very best wordsmiths. For centuries Japanese writers have captivated and surprised their readers, giving them pause for thought along the way. And in very many instances they have done so through elegant short-form formats.

The typical definition of a short story is a piece of narrative prose that can be read in one session; being shorter than a novel, but as complete in terms of storytelling. It’s fitting then that in Japan, a nation known to have mastered the art of the miniature, the format is flourishing, with thousands being penned every year.

New, aspiring and established authors continue to write brilliant short stories and novella that are morphing into new exciting styles and formats that frequently win literary awards.

Japan has an incredible history of short-form fiction that is as rich as it is diverse. There is everything here from verse to the modern short story. Going back to the 10th century, Japanese readers have been captivated by tales of time-travel and shape-shifting.

Then, of course, there are the evocative and deftly crafted poetry collections of old, such as the Manyoshu, Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves. All of which gave rise to haiku and tanka, the hugely popular Japanese-style of poetry that continues to thrive today in a world of digital paperless publishing. Tens of thousands of people in Japan and across the world now happily publish and read tanka and haiku online.

Some academics, including the linguistics historian Susumu Ono (1919-2008), have argued that the Japanese word utsukushiii, beautiful, is an adjective that expresses affection for ‘diminutive objects.’

The word, utsukushiii, was used in the famous Japanese short story the Tale of the Bamboo Cutter, Taketori monogatari, also known as Princess Kaguya, which appeared in its current form between 939 and 956. The tale is better known today because of the 2013 Studio Ghibli animated film. When the childless bamboo cutter and his wife find a small diminutive glowing child within a stick of bamboo they utter the word utsukushiii with delight.

The word is also used in the Manyoshu, Japan’s oldest poetry anthology, as a word for love and admiration of many things including the small and short.

- Japan’s long history of blending brevity and beauty

T

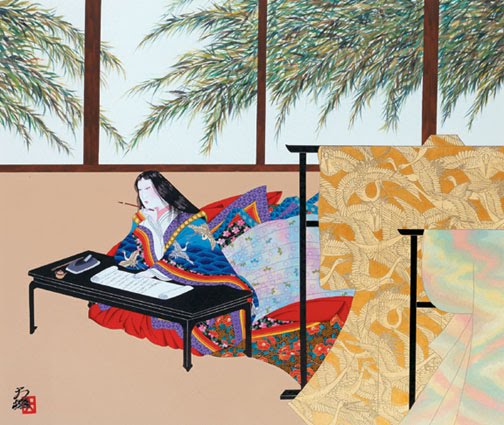

he best-known Japanese literary allusion to the admiration of all that is small was written by one of Japan’s first pioneering female authors, Sei Shonagon (966-1025) who formed part of a group of women who have been dubbed the world’s first Chick-Lit authors. In her The Pillow Book she wrote the following: “All things small, no matter what it is, are beautiful”. And by this she means everything including the Zen-like beauty of brevity and short prose.  Sei Shonagon writing her famous Zuihitsu work, The Pillow Book. Image: Public Domain

Sei Shonagon writing her famous Zuihitsu work, The Pillow Book. Image: Public DomainThis all took place centuries before the term Flash Fiction (fiction of extreme brevity) was coined, or the appearance of Twitter, the dominant short-form writing of our era, which has struggled unsuccessfully to restrict posts to a mere 140 characters (compared to the 17 syllables allowed in traditional haiku). The Japanese haiku format has managed to maintain its structure and rules and is still recognised internationally for its elegance, grace and wit.

Japan’s short-form writing isn’t limited to these popular forms of poetry or to a single genre. The long tradition of short story writing in Japan is broad based and has continued mostly uninterrupted until today.

The multi-nominated and award winning authors Kanji Hanawa, Kazufumi Shiraishi, Mitsuyo Kakuta, Yasumi Tsuhara and the madcap surrealist Yasutaka Tsutsui represent a handful of the many prominent and respected contemporary exponents of the art; who continue to write short stories even after they have become established Japanese literary figures.

The Nobel Prize-winning author Yasunari Kawabata (1899-1972) was a prolific short story and novella writer who also actively encouraged others to follow suit. Ryunosuke Akutagawa (1892-1927), after whom one of Japan’s most sought-after prestigious literary awards is named, was another.

Akutagawa is best known outside Japan for his first published short story ‘In a Grove’, which cleverly employs multiple narrative viewpoints in the form of witness statements of a single crime, a rape – giving the impression that reality is never what it first seems. This story’s unique multi-perspective structure and ambiguous narrative was unlike most typical translated Western stories available at the time in Japan. Readers of ‘In a Grove’ are left totally unsure as to the true outcome of this intriguing but compact tale. An authentic reflection perhaps of the real world in which the true nature of things cannot always be readily determined.

The award-winning film ‘Rashomon‘ based on Akutagawa’s story directed by Akira Kurosawa (1910-1998) introduced similar techniques to the world of cinematic storytelling. Akutagawa also wrote many others brilliant short stories including, for example, ‘The Hell Screen’, ‘Kappa’ and ‘The Life of a Holy Fool’.

Another Japanese master of the short story, from a very different genre, is the science-fiction writer Shinichi Hoshi (1926-1997), who also has a literary award named after him. He wrote thousands of short stories, many of which would now be defined as Flash Fiction. One of his best-known short stories is ‘Bokko-chan’, written in 1963. It is only six-pages long and a favoured text of Japanese language students looking to read their first Japanese short story in Japanese. It is about a glamorous young female bar hostess named Bokko-chan. No one knows or suspects that she is actually a robot designed by the bar’s owner. She helps increase the bar’s takings through two simple functional abilities, namely by making simple conversation offering basic replies or just repeating what she hears; and by being able to drink alcohol when offered to her by visitors that frequent the bar. Inevitably, one of the bar patrons falls in love with her, with dire consequences.

- The long and the short of it: modern Japanese short stories are a Western import

D

espite this rich history, the modern Japanese short story is actually a foreign import. The modern format emerged in the United States, France, Germany, and Russia almost simultaneously in the 19th century, with various writers making major contributions. It is usually American writers like Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804-1864), Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849) and Herman Melville (1819-1891) who are generally credited with writing some of the very first modern short stories. The new format reflected changing media consumption, as well as the growing popularity and increased access to journalism. Realistic narratives that reflected familiar sounding events and the personalities of the time became very popular.

In his 1846 essay, The Philosophy of Composition, Edgar Allan Poe wrote: ‘a short story should be read in one sitting, anywhere from a half hour to two hours.’ According to Poe, who has had a major impact on many Japanese writers and is still respected today, ‘A short story is one that concentrates on a unique or single effect and in which totality of the effect is the main objective’. In contemporary fiction, a short story can range from 1,000 to 20,000 words.

Many of the world’s greatest authors also admired and wrote short stories. Among them, Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910), James Joyce (1882-1941), and J. D. Salinger (1919-2010) to name just a few. But in recent years the short story has been in decline in most countries, with the exception of Japan. Indeed, several journalists and commentators have written about its gradual global demise, and fall from grace – even in America where it all began.

While many amateur writers outside Japan use the short story format to hone their writing skills, masters of the genre in Japan are dedicated to the format and never feel compelled to graduate completely from the short to the long.

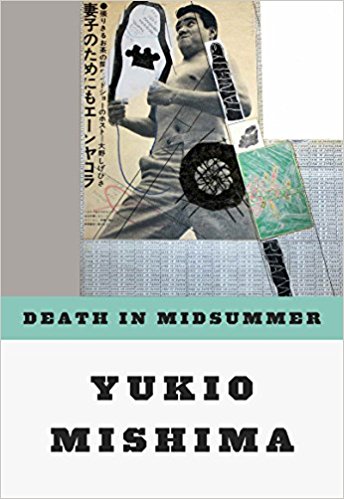

A collection of nine short stories by Yukio Mishima published in English translation in 1996 by New Directions.

A collection of nine short stories by Yukio Mishima published in English translation in 1996 by New Directions.‘It is,’ said Mishima, ‘a sort of, four round match for green boy in boxing. If he can fight four rounds, he can fight five rounds, six rounds, and more and more.’ in other words, if you can take the criticism and the knocks and stay on your feet you have a potential writing career ahead of you.

It is widely known that Kawabata, the great supporter of the format and a future Nobel Prize winner, who became a close and valued friend of Mishima, helped and encouraged Mishima in his early short story writing phase, something that Mishima acknowledged and was incredibly grateful for. ‘He was extremely kind to me, to help me, to show my short story on literary magazine called Human, which was very popular at the period’, explained Mishima publically to a group of Western journalists, ‘Because of him,’ he continued, ‘I became to have very very small fame as short story writer, as a newcomer in literary field. But still I was out of fashion’.

This, however, changed instantly with the publication of Confessions of A Mask in 1949, though its overnight success did not put an end to Mishima’s short story writing. Like most of Japan’s best writers, he kept writing them.

Despite Japan’s long literary history and its association with the art of the short story, this fact simply isn’t acknowledged by authoritative sources like The Encyclopaedia Britannica and Wikipedia in their entries on the evolution of short stories and short form fiction. They both state confidently that the short story can be traced back to the earliest development of the written word, and that the modern short story we are familiar with today really evolved in the 19th century. Russia, America, India, Egypt, Greece and Nicaragua all get a look in. But poor Japan, nor a single Japanese author get a single mention.

This may well be a symptom of a phenomenon known as the Galapagos syndrome, a term first used to describe how parts of Japanese culture and industry have developed in isolation of the rest of the world and globalization. The syndrome can, to a large extent, also be applied to Japan’s community of authors, publishers and readers. For a long period of time, the West and Japan were both blissfully unaware of each other’s literary output.

The modern short story arrived in Japan relatively late, in 1890, some time after most other countries. It is generally agreed that the first written was ‘Maihime‘ (The Dancing Girl) by Ogai Mori (1862-1922). And its impact on both Japanese readers and writers was not insignificant.

The story, which is said to be partly autobiographical, was Mori’s first published work of fiction and was initially published in the relatively new and influential magazine Kokumin no Tomo (The Nation’s Friend). Mori had, in fact, spent four years in Germany between 1884 and 1888, where he is likely to have come across many short stories and short story writers.

Many Japanese forms of artistic expression develop in splendid isolation and can take time to take root. In some instances a creative impasse hinders progress, and it can take a stimulus from abroad to spawn a new initiative or creative approach, one that enhances or radically overhauls the original creative concept. Mori’s short story certainly wasn’t an instant hit, but gradually became recognised as an important milestone in Japanese literature, and is, in fact, still studied today by Japanese students.

Interestingly, Mori’s sister would become the maternal grandmother to Shinichi Hoshi, the prolific Emmy winning writer of flash fiction or shyoto-shyoto, short short stories, as they are known in Japan. She brought him up, and probably read him some rather intriguing tales when he was child.

Japanese literary magazines, including Shincho, on sale in a Tokyo bookshop. Image: Red Circle Authors Limited

Japanese literary magazines, including Shincho, on sale in a Tokyo bookshop. Image: Red Circle Authors LimitedNew printing technologies were beginning to emerge against a backdrop of social change – triggering the launch of a significant number of literary journals and publications. Shincho (New Tide), for instance, was launched by the respected publisher Shinchosha in 1904.

These new magazines and journals created demand from both readers and editors for short stories and serialised novels in the same way as Western publications like The Strand Magazine, launched in 1891, helped popularise the format, and new genres in England. The first Sherlock Holmes short stories by Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930), for example, were published in The Strand Magazine, which also serialised The Hounds of the Baskervilles.

The profitability of these Japanese publications is no longer as attractive as it would have been back in the Meiji Era, but most major Japanese publishers still publish literary journals today. Contemporary writers have built on this rich legacy and still receive support from Japanese publishers and readers when they write short stories. This modern foreign import has, it seems, been digested, refined and taken to a new creative level. Today, new initiatives are underway to make more and more of the best Japanese authors’ works available in translation to the world at large.

- Small is beautiful

F

ollowing the Second World War the prevailing ethos in the West was that ‘Bigger Was Better’ and that everything in the United States was bigger and better than anything anywhere else. This gave rise to industry consolidation and the creation of huge multinational companies. Scale is a world still loved by today’s technology entrepreneurs and evangelists. Naturally, massive consolidation has also taken place in the publishing industry, with many small publishers being absorbed by large American or German groups. That said, the Japanese mentality has always been different. But it took the publication of a book by an economist to highlight what most Japanese people already knew to be true, namely that big is not always better. E. F. Schumacher’s book Small Is Beautiful: A Study of Economics As If People Mattered, was published in 1973, during the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries’ (OPEC) oil embargo in retaliation for the West’s support of Israel in the Yom Kippur War. The period became known in Japan as the Oil-Shock. The book had a major international impact and was cited by The Times Literary Supplement as one of the 100 most influential books published since the war.

In the book, Shumacher argued that small cities, companies, cars, states and organisations were better for mankind and most importantly for the environment. The book is now dated and no longer required reading at business schools, where most students are focused on winner-takes-all strategies, the digital first mover advantage, and the associated network effect and benefits of being big – as well as consolidating market power through data.

However, fashions and business strategies change with the ebb and flow of business cycles. Increasing concern about faceless unmanageable large multinational organisations, data privacy, and environmental impact may mean the book’s time could come again. As it happens, Japan is still one of most fragmented major publishing markets where consolidation has been elusive. And its many publishers have stuck with their strategy of developing new generations of interesting authors by supporting and encouraging short story and novella writing.

The art of the miniature is deep rooted in Japan, and everyone can quickly cite numerous examples of Japanese objects that are small and beautiful, such as bonsai, the Sony Walkman, or netsuke, and there is also the current and somewhat bizarre fad of cooking tiny meals using miniature-cooking utensils.

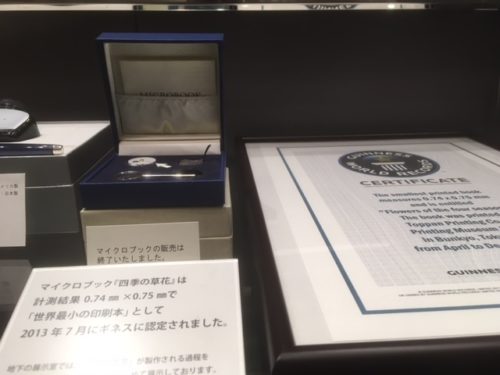

The world’s smallest book with its certificate from the Guinness Book of Records on display at the Print Museum in Tokyo. Image: Red Circle Authors Limited

The world’s smallest book with its certificate from the Guinness Book of Records on display at the Print Museum in Tokyo. Image: Red Circle Authors LimitedDue to the nation’s particular strength in this area of science, when Nature,the prestigious international journal of science, decided to launch a new publication about the science of the very small, Nature Nanotechnology, it placed one of its editors in Tokyo to hunt-down research papers from corporate, government and university research laboratories.

Japanese scientists and engineers have even tried their hand at short stories. A group of software engineers created an algorithm designed to use artificial intelligence (AI) to generate short stories. And, of course, they submitted the fruits of their labour not to a scientific journal like Nature Nanotechnology, but to the Hoshi Prize – the science fiction short story literary award set up in 2013 named in honour of the author of the short tale, ‘Bokko-chan’ about the robot bar waitress.

The award is consciously open to all possible authors, including computers and aliens – not to mention humans. It deliberately sets such wide criteria to help expand the concept of science fiction – making the award itself an embedded part of the genre. The AI authored short story made the initial screening and generated huge international publicity but didn’t make the shortlist. It had some very stiff competition. Amusingly, its title was, ‘The Day a Computer Writes a Novel’ (Konpyuta ga shosetsu wo kaku hi).

The Hoshi Awards’ first winner was a male human named Shinichi Endo, whose prize-winning story was written in the style of a scientific article, the kind that a Tokyo-based Nature Nanotechnology editor might be expected to find and publish. But this fictional academic article is not one from the present, but one written by advanced AI in the year 2064.

- Are we on the cusp of a new golden age of short stories and mini-books?

P

ublishers are also now picking up on the attractiveness of the short story. In India, for example, Penguin Random House, the world’s largest publisher, recently announced the launch of a new digital short story imprint: Petit. The new imprint will publish short reads of approximately 50 pages designed for ease of reading across digital devices. In parallel, many of the world’s leading newspapers have launched online sections dubbed Long Reads on their websites, which are longer than your typical news story, but similar in length to some short stories. Perhaps with our changing media consumption patterns the short story is about to enjoy an international revival.

Newspaper headline writers in Britain have picked up on the trend and have acknowledged it with lighthearted headlines like: Let’s not drag this out: the short story is back and Short story revival cuts novels down to size – accompanied by articles about the recent increase in sales of short story collections. This has been partly triggered by big names like the American actor, Tom Hanks whose book, Uncommon Type has been something of a hit. But there does seem to be an emerging new trend.

According to recent reports, more than 690,000 short stories and anthologies were sold in the United Kingdom in 2017, generating almost £6 million in sales, the highest level for short stories in about seven years.

Connoisseurs of Japanese literature know that to enjoy the best of Japanese fiction and creative writing you really need to read short stories. Perhaps, in our time-scarce world of poor and unreliable content, the short story’s time has come. Like sushi, now considered a special treat and enjoyed by everyone, these aesthetically pleasing, small and easy-to-digest packages have been enjoyed and developed quietly for decades in Japan. The time to read them in translation has now surely arrived.

© Red Circle Authors Limited

Second-hand Japanese books on sale at a Tokyo bookshop. Image: Red Circle Authors Limited

Second-hand Japanese books on sale at a Tokyo bookshop. Image: Red Circle Authors Limited