All Out!!, a Japanese manga, written by Shiori Amase launched in a monthly magazine in 2013 by Kodansha, one of Japan’s leading publishers. It was released as an anime in 2016. Image: Public Domain.

All Out!!, a Japanese manga, written by Shiori Amase launched in a monthly magazine in 2013 by Kodansha, one of Japan’s leading publishers. It was released as an anime in 2016. Image: Public Domain.W

hen Rugby, the all-out macho sport of the elite, officially arrived on Japanese shores in the 1890s, the country was experiencing a revolution-like period of massive cultural and technological change that encompassed everything, literature and sport included. Even so, it is hard to imagine what people must have thought when they saw a rugby ball for the very first time. Baseball, an early American import arriving in 1872, quickly gained popularity, but was not considered by some of Japan’s elite as masculine enough or sufficiently in tune with Japanese values and its samurai spirit of self-sacrifice, extreme discipline and loyalty.

This period was known as the Meiji Era (1868-1912). Adopting Western sports and reading about the West in books that had been translated into Japanese for the first time became an essential part of the modernisation and internationalisation of Japan, its industry and educational system.

Learning and teaching such new Western sports as baseball, basketball, gymnastics, golf, rowing, athletics and rugby formed part of this programme of change. Here were sports that would instil self-discipline, morals and values; and put Japan on par with the world’s other leading civilisations.

Individual sports were also thought to reflect national character and social privilege. And large swathes of the Japanese elite at that time, viewed rugby as a superior ‘Japanese’ sport to baseball, which was generally seen as lacking integrity, and a game based around ‘theft’.

-

- Land of the rising scrum

R

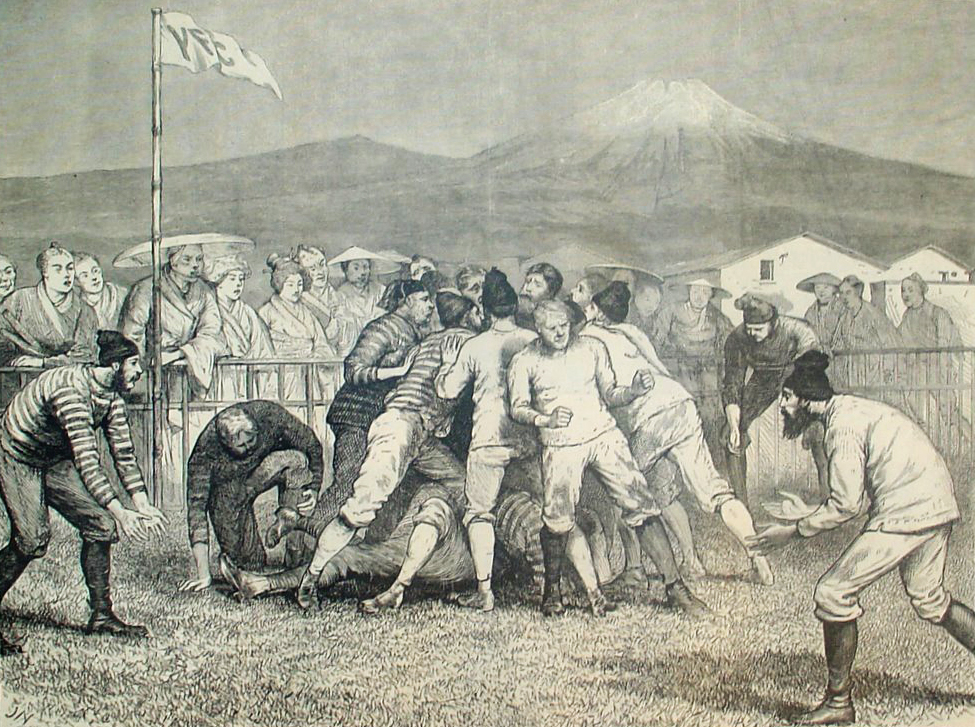

ecords show that the very first rugby team formed in Japan and the first game played in the country was in 1866, by the Yokohama Football Club, before the start of the Meiji Era and the arrival of baseball. Several members of the club, all of whom were non-Japanese living and working around the Yokohama port (which was already open to international trade), were former students of Rugby School in Warwickshire, England, the school from which the game takes its name and acquired its set of rules that were codified in 1845 by three of its pupils.

Ruby Football match in Yokohama. Harper’s 1874. Image: Wikipedia

Ruby Football match in Yokohama. Harper’s 1874. Image: WikipediaIn 1889, the Cambridge graduate Edward Bramwell Clarke (1874-1934) and Ginnosuke Tanaka (1873-1933) who had been to school and university in England, officially “introduced the game” to Japan with the creation of a team at Keio University, a private university in Tokyo, where Clarke was teaching English.

In 1891, with only one year or so to learn the rules and practice, the Japanese students from the university played against British members of the Yokohama Athletic Club.

This match is generally cited as Japan’s first official game of rugby, which, unsurprisingly, the Keio students lost by a reported margin of 35-5. However, the heavy defeat didn’t put them off. Rugby is still popular to this day at Keio University. And this game is the historic mark from which the game spread to other universities in Japan, with a subsequent knock-on effect in schools.

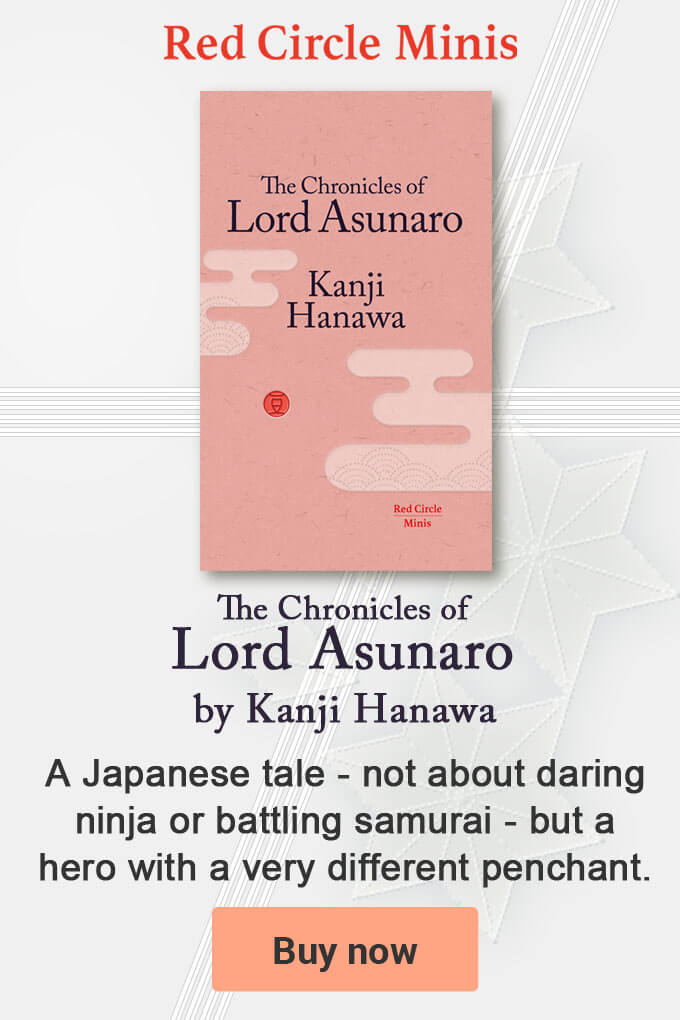

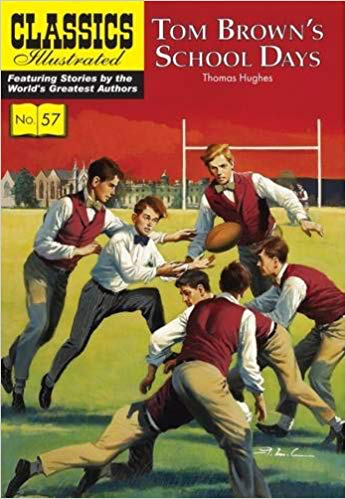

Within a decade, in 1899 an abridged edition of Tom Brown’s School Days, a novel written in 1857 by Thomas Hughes (1822-1896) and set at Rugby School, was published in Japan in Japanese. The book contains an account of the game, rugby, as well as stories of Tom’s school life at the English public school founded in 1567.

Cover of an illustrated edition of Tom Brown’s School Days by Thomas Hughes, which become probably the most popular ‘textbook’ amongst Japanese High School students during Meiji Period.

Cover of an illustrated edition of Tom Brown’s School Days by Thomas Hughes, which become probably the most popular ‘textbook’ amongst Japanese High School students during Meiji Period.The very first actual Japanese book on the game of rugby, Ragubi Shiki Futoboru (Rugby-Style Football), was published a few years later in 1909, a digital copy of which can be accessed online at the Japan’s National Diet Library.

The book critiques baseball, insisting that rugby is superior in terms of its sportsmanship, saying in its foreward: “Let’s play rugby, not baseball!” and quotes a famous Japanese baseball player Shin Hashido (1879-1936) to strengthen this line of argument. “Rugby may become a very important sport to me… In the future, I will play rugby instead of baseball,” says Hashido, who was a star baseball player and captain of the team at Waseda University, like Keiko a prestigious private Japanese university.

He would go on to become a baseball hall of fame star (inducted in 1959). Books of this period in Japan mostly focus on introducing new sports and their rules to Japan, not on tactics and game-winning strategies or inspiring character-building narratives associated with the sport.

The American-derived sport baseball, despite its popularity, was controversial and considered harmful by some sections of the Japanese press and society, which argued that playing the sport would turn students into ‘non-achievers’ and ‘delinquents’, not the super disciplined loyal heroes Japan wanted to develop.

In 1911, the Tokyo edition of the Asahi Shimbun, a leading Japanese newspaper, published a series of ‘anti-baseball articles’, one of which quoted comments by Inazo Nitobe (1862-1933), a prominent figure from an elite samurai background who later became an international diplomat noted for his book written in English, Bushido: The Soul of Japan. In that book Nitobe describes the sources of bushido (the way of the warrior) and those virtues most admired in Japan: self-control, duty, politeness and courage.

He is reported by the Asahi, as saying: “Playing baseball could be likened to picking a pocket”. He is also reported, to have said: “To play baseball, you must be able to deceive the opposing team and lead them into a trap”, and “you must always sharpen your senses so that you will never miss the chance to steal a base”.

Although Americans can play such a sport, he argued: “British and German people cannot play it. The British national sport is football, and to play football, you have to be strong and brave enough to keep the ball without fearing injury. You must keep the ball even if your nose is crooked, or your jawbone is fractured”. Americans, he believed, “cannot play such a tough sport”.

Subsequently, Keio’s great Tokyo rival Waseda, where Hashido captained the baseball team, decided to follow the rugby trend by becoming the fourth university in Japan to establish a team and a rugby club in 1918. This said, it took Waseda, now one of the strongest and most successful university rugby teams in Japan, 28 years to beat Keio for the first time.

The two universities have been playing each other on the 23 November annually ever since, in a match known as the Soukei-sen. The game is a major event with tens of thousands attending.

Katsuyuki Kiyomiya, one of Japan’s most prominent coaches, a Waseda graduate and the team’s coach between 2001 and 2006, wrote a book entitled Ultimate Crush about the challenge of creating winners out of Waseda students and preparing them for this high profile annual match. An English edition, translated by Ian Ruxton, was published in 2010.

Many sports quickly established national federations in Japan, The Japan Alpine Club in 1905, Middle Schools’ National Baseball Federation in 1915 and the Japan Amateur Rowing Association in 1920. And Baseball was the first sport to be professionalised in Japan with the establishment of a professional league in 1936.

Nonetheless, it took time for ruby to find its footing. The Japan Rugby Football Union was founded in 1926, according to The Oval World, a global history of rugby, by Tony Collins; and elite private Japanese universities joined with the leading public universities (Tokyo and Kyoto) to form a National Federation for Rugby. This increased momentum for the sport in Japan and helped cement the position of rugby as an aspirational sport of the elite.

Despite this and the strong preference of some of Japan’s elite, rugby lost the battle of the balls; and baseball is now Japan’s most popular professional sport. According to some surveys, it has even overtaken Sumo, Japan’s National Sport. Despite this, rugby is generally considered Japan’s third-sport behind baseball and football (soccer).

-

- Japan’s writers tackle the oddball sport

T

he Japanese author Yukio Mishima (1925-1970), the most internationally famous Japanese author of his generation – and interestingly one of David Bowie’s (1947-2016) favourite authors – briefly tried his hand at the sport. He joined his school rugby club at Gakushuin, a Tokyo school that was originally setup to educate Japan’s upper-class and nobility. It was an unhappy, but important, experience for him. His teammates apparently found his literary ambitions laughable. The experience is reflected in his early writings in the semi-autobiographical Tabako (Cigarettes), which was first published in the magazine Ningen in 1946 on the recommendation of Yasunari Kawabata (1899-1972), the author who was selected over the younger Mishima for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1968. Incidentally, Cigarettes was Mishima’s debut work into the bundan, or literary establishment.

The short story’s protagonist is a sensitive individual who is the victim of a rough, brutal and bullying rugby club. Mishima switched from rugby, away from team sports, to kendo and bodybuilding; and is better known today in his works for his love of athleticism, masculinity and homoerotic imagery, and, of course, his suicide.

Another high profile Japanese author with a rugby connection is Soji Shimada, who is often referred to by his fans in Japan as the ‘God of Mystery’ as he reinvented and popularised classic whodunit-style novels and helped establish a new modern detective fiction genre, known as shin-honkaku, new orthodox or new classical detective novels, a Japanese genre that features Sherlock Holmes-style deduction, reason and logic.

Shimada, a Beatles-loving anglophile, played right wing in his high school rugby team, which in contrast to Mishima was a positive experience that he managed to convert into his most successful books. His tough no-nonsense detective Takeshi Yoshiki, the main character in one of his two major series, is a former rugby player. The 14-book Yoshiki series has been very successfully adapted for television, making the rugby-loving Yoshiki a household figure in Japan.

-

- After the war: a second try

R

ugby was restricted and at times banned in Japan during the Second World War. After the war the Allied occupying forces banned Japanese martial arts, such as kendo, that had been associated with military training. They encouraged the spread of Western sports and baseball in particular, which, with a bat and a ball and a couple of friends, was relatively easy to try. The reestablishment of the professional league was quickly approved in 1946. This, and having to find fifteen friends to create a team, as well as the austerity of the times, however, did not put everyone completely off rugby. Rugby remained an aspirational sport for some of Japan’s elite and was picked up again quickly after the end of the war.

Perhaps the subtleties of social rank in Japan, today generally obscured within Japan’s mass middle-class, also had an impact, like in some other countries, limiting access and widespread interest in the game.

The master short-story writer and Akutagawa Prize-nominated author Kanji Hanawa recalls that he and his school friends at Seijo Gakuen High School (a well-regarded private school) including Seiji Ozawa (who went on to become one of Japan’s most renowned conductors) made a rugby ball out of old socks and tried to get a makeshift game going without proper equipment, understanding of the rules, or having heard of the expression ‘touch-rugby’.

Despite the death of many of the first generation of rugby players in the war, the popularity of the sport grew; and Japan now has over 120,000 registered players, and more than 3,000 registered teams.

According to some analysis, Japan is the world’s fourth largest rugby-playing nation. But there is a large gap between Japan and the third largest rugby nation, South Africa, who have double the number of senior male players. England and France are ranked number one and two when measured on this basis.

Japan now has a professional league called the Top League with company-owned teams and well-paid players, many from overseas. In addition to this and the continued popularity of university level rugby, high school rugby is also thriving.

In fact, Japanese high school and university sports are often more popular, and better attended, than many professional and international games across all sports, including rugby.

The annual National High School Rugby Tournament is a major event. It is held at Japan’s so-called rugby ‘Holy Ground’, Hanazono in Osaka, where there has been a rugby stadium since 1923.

Teams from all of Japan’s 47 prefectures compete to become national champions, something that has made captaining the winning team there the dream of many Japanese schoolboys.

The stadium has a capacity of 30,000 and games are broadcast on national television. In recent years more than 100,000 people have attended the competition’s matches.

Novels, like Tom Brown’s School Days, can be highly influential with very long-term lasting social effects. But live sports can on occasion create defining moments and magical, unforgettable collective memories that bring nations and people together. September 19, 2015 was one such day for Japanese rugby.

Cover of Japanese rugby magazine All Out Rugby Football Magazine

Cover of Japanese rugby magazine All Out Rugby Football MagazineThe Japanese rugby team, the underdogs, pulled off ‘a miracle’, and possibly one of the greatest rugby upsets ever, by beating two-time world-champions South Africa with the successful completion of their last high risk try-winning move in the last minute of the game.

It was fairy tale stuff. Captivating all neutral fans watching including JK Rowling, of Harry Potter fame, who tweeted at the end of the game: “you could not write this…”

Rugby book by Japan’s national team ‘mental-coach’ featuring Ayumu Goromaru, one of the heroes from Japan’s 2015 World Cup performance in England.

Rugby book by Japan’s national team ‘mental-coach’ featuring Ayumu Goromaru, one of the heroes from Japan’s 2015 World Cup performance in England.The team’s next game, against Scotland, attracted some 20 million viewers, and Japan’s final match versus Samoa was watched by 25 million people; the largest national audience for a single game in rugby’s history.

Interestingly, 2015 was not the first time the Japanese national team made a lasting impact on non-Japanese fans when playing overseas. In 1973, the ‘bravery and adventure’ of the first Japanese national side (known as the Brave Blossoms) to play in Wales, deeply impressed the locals.

Unlike some teams that are famous for their war dances, the Japanese team bow and are noted for their respect for fair play, the rules and their determination. Despite being outplayed the team never gave up.

The team’s attitude inspired ‘the great Bard of Welsh rugby’ Max Boyce, a very popular singer-comedian in the 1970s who sang at the Opening Ceremony of the 1999 Rugby World Cup in Cardiff, to write an ode to Japanese rugby in a tribute song, entitled: Asso Asso Yogoshi.

One of the lines from the song, which would probably now be considered inappropriate, was: ‘In Penygraig we play first game / Papers says we not to blame / Papers say we not lack class / Just not used to 5ft grass.’ Like the team, the song became a hit, attracted attention and was played regularly by one of Britain’s most popular national radio stations, Radio One.

-

- The ultimate rugby crush

L

inks between rugby, literature, creative writing and fiction publishing may be hard to find, but they certainly exist – even though they can at times be distinctly odd. New Zealand rugby romance literature, for instance, is alive and well with authors like Rosalind James of Just Say (Hell) No. Even the Romance publisher Mills & Boon has got in on the act with an eight book tie-up licensing deal with the Rugby Football Association. The publisher’s stated aim is to: ‘do for rugby what Jilly Cooper did for polo – to give it an air of sexiness and glitz and glamour’.

Japan edition of At the Argentinean Billionaires Bidding by India Grey and Tomomi Yamashita, published by Harlequin Comics in 2016.

Japan edition of At the Argentinean Billionaires Bidding by India Grey and Tomomi Yamashita, published by Harlequin Comics in 2016.These books will no doubt help make rugby players the ultimate crush for the next generation of teenage girls, and perhaps also increase the sport’s attractiveness amongst women. We will have to wait and see.

Another example of a rugby novel with a rather different type of readership is Work, Sex and Rugby by Lewis Davis, about one man’s ‘odyssey through a weekend of drinking, rugby and women’ that enjoys the rare distinction of being voted:”the best book published describing Wales”.

Japan’s best-known rugby writer is Nobuhiro Baba, author of the novel Ochikobore Gundan no Kiseki (Miracle of the Drop Out Group) and other titles.

Winston Churchill (1874-1965) reputedly said, “rugby is a hooligan’s game played by gentlemen” and Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) is often attributed with the statement: “rugby is a game for barbarians played by gentlemen. Football is a game for gentlemen played by barbarians”.

Baba’s 1981 book, based on a true story about a former Japanese international rugby player who becomes a teacher and coach at a failing high school in Kyoto, plagued by delinquency and extreme behaviour, is a unique and popular Japanese spin on this.

After a massive initial defeat, the player builds a team, convincing a local hooligan – known as the worst troublemaker in Kyoto – to join. The team then goes on to win the Kyoto Prefecture Rugby Tournament, turning around the fortunes of failing school in the process.

The narrative may not be the best one to describe modern-day Japan, but it struck a chord with its audience who could undoubtedly relate to the familiar theme of sacrifice for a team and how belonging to a group can turn everyone into winners.

Holding Out For A Hero, a song written by Jim Steinman and Dean Pitchford, which most people know as the Bonnie Tyler theme song to the 1984 Hollywood blockbuster Footloose was adapted and sung by Miki Asakura as the theme song for a 26-part Japanese television adaptation of the book, broadcast as School Wars, which was launched in October 1984, eight months after Footloose’s release.

The powerful, uplifting song, like the television drama – which some people argue is Japan’s best ever television series – was a 1980s favourite in Japan and is still popular, despite being hard to sing in karaoke bars.

The series was subsequently released as a full-length feature film titled School Wars Hero in 2004, directed by Ikuo Sekimoto. In the film the team ends up at the sacred Hanazono ground, the location of the annual finals of the All Japan High School Rugby Tournament.

A more recent manifestation of rugby in popular culture is the manga, All Out!!, which started off as a serial in a magazine and then launched as an anime in 2016. Despite being written by a woman Shiori Amase, and its imagery of male bonding, the manga is a classic one for young boys and should not be confused with the so-called Boys Love (BL) genre. BL is a popular Japanese genre of fictional media, mostly manga, focusing on romantic or sexual relationships between male characters, typically marketed to a female audience and usually written by female authors.

Another example of a rugby manga, Meisetsu Technical High School Rugby Football Club. Published in 2010.

Another example of a rugby manga, Meisetsu Technical High School Rugby Football Club. Published in 2010.All Out!! is not yet a worldwide smash hit like its equivalent football manga Captain Tsubasa, which was launched in 1981. Captain Tsubasa has been broadcast in anime format in 60 countries and boasts some of the world’s most famous footballers as fans. It is still, however, early days for All Out!!.

Diversity is one of the buzzwords of our age and this includes diversity in sport as well as business.

Rugby is no longer considered a sport just for white men, some of whom go on to have successful careers in banking. According to the HSBC report, The Future of Rugby, women’s rugby is now the world’s fastest growing sport. And Japan is no exception.

Cover of book published in 2011 by Shogakan titled Rugby For Girls by Manabu Matsuse.

Cover of book published in 2011 by Shogakan titled Rugby For Girls by Manabu Matsuse.The Japanese women’s rugby team founded in 1991 have followed in the footsteps of the men and competed in World Cups, and have also been crowned Asian Champions.

However, they have not yet completely outshone the men’s team like the Japanese Women’s Football team who beat the U.S. team on penalties in 2011, becoming the first Asian team to win a FIFA World Cup final. Nevertheless, Japanese women rugby players are highly capable, determined and qualified, despite being largely unrecognised outside Japan.

After Eddie Jones’ 2015 success in taking a diverse multi-cultural Japanese team to a level on par with the best in the world, Masanori Mochida, the President of Goldman Sachs Japan, who played fullback for Keio University in his rugby playing youth, hired Jones to join the bank’s advisory board, to help it build better teams.

Tokyo subway poster promoting the once in a life time opportunity of attending the Rugby World Cup in Japan. Image: Red Circle Authors Limited.

Tokyo subway poster promoting the once in a life time opportunity of attending the Rugby World Cup in Japan. Image: Red Circle Authors Limited.He and his Keio team, like so many other teams, lost to Waseda, an experience that Mochida cites as an early and important character-building life lesson.

The Rugby World Cup, the ninth, will be held in Japan in 2019, the first time in an Asian country. Fans in Japan and from around the world will enjoy this unique combination.

It is highly unlikely that fans will be treated to a rendition of Asso Asso Yogoshi, but they will no doubt be greeted by the Japanese cover version of Holding Out For A Hero, alongside more traditional rugby chants.

International fans will be exposed to Japanese rugby like never before, not just the country’s stadiums, fans and national team, but also to new types of rugby culture and vocabulary – be they manga, anime or Japanese words like konjo (guts).

After the final match, when the international media scrum and rugby fans from across the world have left Tokyo in December next year, perhaps the spectacle and the inevitable dramas on and off the field will encourage some to try their hand at creative writing; penning a new form of Japanese bonkbuster; a bestselling noire novel; a rugby haiku; a new lyric; or short story that rugby fans can sing about or read with delight for years to come.

© Red Circle Authors Limited

FEBRUARY 8, 2009 - Rugby : Japan Rugby Top League 2008-2009 Play off Tournament Microsoft Cup Final between TOSHIBA Brave Lupus and SANYO Electric Wild Knights at Chichibunomiya Rugby Stadium on February in Tokyo, Japan. (Photo by Tsutomu Takasu) - Wikimedia

FEBRUARY 8, 2009 - Rugby : Japan Rugby Top League 2008-2009 Play off Tournament Microsoft Cup Final between TOSHIBA Brave Lupus and SANYO Electric Wild Knights at Chichibunomiya Rugby Stadium on February in Tokyo, Japan. (Photo by Tsutomu Takasu) - Wikimedia