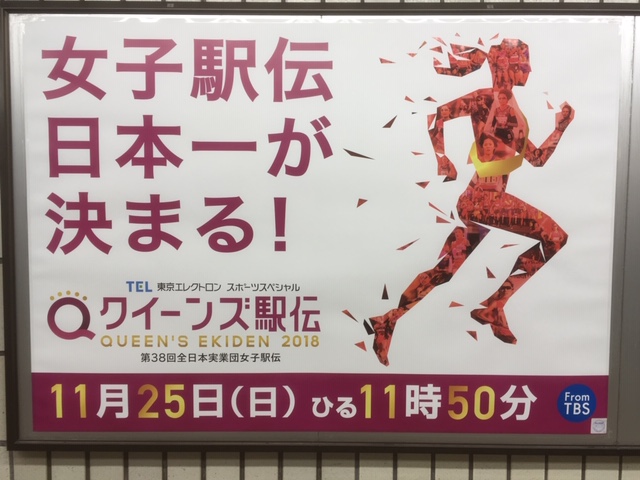

Promotional poster on the Tokyo Metro for the Women’s 2018 Eikiden Race that, according to the slogan, will determine who is the best in Japan. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.

Promotional poster on the Tokyo Metro for the Women’s 2018 Eikiden Race that, according to the slogan, will determine who is the best in Japan. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.S

ome nations have running in their blood. Japan is known for its discipline, long hours and endurance, as well as its respect for hard work. Long-distance running and marathons, and the discipline they engender, are therefore perfectly at home in Japan. Before jogging and marathons became trendy in the West, and long before Phil Knight famously visited Japan in 1962, which led to him founding the firm that went on to become Nike, Japanese runners had been enthusiastically pounding the streets in long-distance races, since at least 1917.

Japan has internationally famous runners and famous people that run marathons, and others who just prefer to write about running, or watch and read from a comfortable distance. And it has its very own rather wacky races.

Over the last decade, the number of people taking part and officially completing marathons in Japan has more than doubled, and more than 50 marathons take place every year. These include famous and important ones like the Tokyo Marathon, but also lesser known ones including those run at night (Kaga Night Marathon); the Nagoya Women’s Marathon, where all finishers get a Tiffany necklace, as well as Sweet Marathons where hundreds of different kinds of bite-size sweets are served at ‘aid-stations’ along the route.

Not all of Japan’s races are the standard marathon length. Initially, the length of a marathon varied, as does the use of the Japanese word marason. It only became fixed and standardized at 26.2 miles at the London Olympics in 1908, when the race started from Windsor Castle.

As most know, the word marathon derives from the name of the location of a famous battle between the Greeks and Persians from where the messenger-runner Pheidippides (530–490 BC) ran to Athens to inform officials of the news that the Greeks had been victorious. Nonetheless, the word is now part of international vocabularies, and has many different meanings and usages.

The Tokyo Marathon is indicative of why some have called Japan the world’s ‘most running-obsessed country’. It is one of the world’s six major marathons and the only one of this group to be held in Asia.

Besides being tough to run, it’s one of the hardest races to participate in – as more than 300,000 people apply for the right to stand on the starting line in its annual ballot for tickets, something that only about 10% or 30,000, win the right to do each year. For marathon enthusiasts who dream of completing ‘the six-majors’ (Boston, London, Berlin, Chicago, New York and Tokyo), just getting a ticket to run Tokyo feels like winning.

Japan’s most famous marathon runner, Yuki Kawauchi, is known as ‘The Citizen Runner’ as he is an amateur with a full-time job as a local bureaucrat for Saitama Prefecture next to Tokyo. In 2018, he made it into the Guinness Book of Records for running 76 marathons with finish times of under 2 hours 20 minutes, becoming the world’s most consistent high-speed marathon man.

Perhaps Japan’s best known person that runs is the author Haruki Murakami, who The New Yorker dubbed: ‘The Running Novelist’, after his book, What I Talk about When I Talk about Running, was published in English in 2008. Long-distance running is not confined to Japanese men of a certain age. It is popular amongst women, including female running stars like Yukiko Akiba. People of all ages run, even 80-year-olds.

-

- Flying-Feet & Relays: Creating Winds that Run through Japanese Fiction

L

ong-distance running is an activity that has long been part of Japanese culture. Hikyaku, flying-feet, runners, who acted as message carriers, played a critical role, akin to the American pony express, in Japan for centuries. Woodblock print by Hiroshige Utagawa (1797-1858) of Hikyaku, Flying-feet runner. Image: Adachi Hanga

Woodblock print by Hiroshige Utagawa (1797-1858) of Hikyaku, Flying-feet runner. Image: Adachi HangaDuring Japan’s Edo Period (1603-1868) runners would run to stations and checkpoints where messages were passed on to the next runner in a type of relay race.

This was before the arrival of new technologies in Japan’s Meiji Era (1868- 1912), when Japan suddenly opened up to the world after more than two hundred years of self-imposed isolation. The arrival of Japan’s first telecommunication line in 1869, and its first railway line in the 1872, both contributed massively to Japan’s modernisation and transformation. In 1917, The Yomiuri, a major Japanese newspaper, sponsored a race along a 508km route over a period of three days, with runners handing over a tasuki (sash-cloth) rather than a baton at each station to the next runner. Ever since, these Ekiden races have been hugely popular in Japan.

The best known of them, which started in 1920, is the Hakone Ekiden, a two-day race with 20 teams of 10 male university students who run from Tokyo to Hakone, close to the foot of Mt. Fuji where a historically important checkpoint on the route to Tokyo was located, and back. The 135-mile race is broadcast nationally on the 2nd and 3rd of January each year and watched by about a third of the population.

Unsurprisingly, with this level of interest in the sport there have also been numerous books and short stories written about runners, running, and the Ekiden. Shion Miura is one of Japan’s contemporary writers who has taken up the Ekiden challenge.

Cover of Shion Miura’s prize-winning novel, Kaze ga tsuyoku fuiteiru, The Wind Blows Hard, published in 2010 by Shinchosha.

Cover of Shion Miura’s prize-winning novel, Kaze ga tsuyoku fuiteiru, The Wind Blows Hard, published in 2010 by Shinchosha.First he needs to find 10 people to join his team. Then they need to train and qualify. It is a classic tale of a group of misfits coming together as a team, growing mentally and physically, and somehow making it to the all-important races where they run alongside some of the most famous university teams in Japan.

The book has two parts: the race to the starting line; and the Hakone Ekiden itself. In the same way as Tokyo Olympiad, the acclaimed documentary film made for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics by Kon Ichikawa (1915-2008), depicts the 1964 Olympic marathon in an almost poetic manner mentioning the runners’ professions and other details, Shion uses each stage of the actual race to describe not just the race and the terrain, but each runner’s background and personal challenges.

The huge media exposure means that teams, coaches and individual runners can capture the nation’s imagination turning them into media celebrities. There are many gripping narratives and stories around this annual event; some turn people into legends, and others create content for novels. Right now, Susumu Hara is one such person. He took over as the coach for the Aoyama Gakuin University team in 2003. Six years later, in 2009, his team qualified for the first time in 33 years for the Ekiden and then they went on to win for an unprecedented record four consecutive years 2015, 2016, 2017 and 2018.

Atsuko Asano is a prolific author of young adult sports related books, often about young men and their relationships, such as the one between the pitcher and catcher in her book series Battery.

As a graduate of Aoyama Gakuin University she published the first of her three books about runners in 2010, The Runner, the year after Aoyama qualified for the Hakone Ekiden. She went on to publish Spikes in 2013 and Lane in 2016.

Asano is also a member of the Japanese Communist Party, and has said she wants to believe in the ‘brilliance of teenagers’ and as a middle-age woman wants to depict adolescent boys that are ‘upright’ and ‘independent’ and ‘strong-willed’ who break society’s perceived barriers and strictures in a way she couldn’t when she was a teenager.

Another important Japanese novel about running, written by one of Japan’s many talented female authors is Isshun no Kaze ni nare, Become the Wind in a Moment, by Takako Sato. This time about sprinters.

Just like long-distance runners, Japan now has many top class sprinters that win international medals in, for example, the 4 X 100 metre relay. The book won the Japan Booksellers award (Honya Taisho) in 2006.

-

- Marathon Monks and Marathon Running Authors

Y

ou only need to see images of Japan’s famous ‘marathon monks’ who have been trying since at least 1885 to reach enlightenment by completing a thousand ‘marathons’ in a thousand days to understand the narrative appeal of long-distance running in Japan. Only some 46 monks have achieved this extraordinary feat of extreme spiritual and physical endurance. The stories of these Running Buddhas who have worshiped at Mount Hiei, northeast of Kyoto, for 1,300 years, have captivated the world. In 2013, when Yasai Sakai, a monk who had completed the Sennichi Kaihogyo twice – only the third monk ever to do so – died, international newspapers such as the London-based Telegraph ran obituaries on him. Sennichi Kaihogyo is a seven-year journey that these ascetic monks believe allows us to reach enlightenment in this life without having to wait to be reborn.

The practice involves circulating the mountains around their temple in a meditative state, making offerings and reciting prayers at temples on route. There is also a 100-day practice as well as the mammoth 1,000-day practice.

The Running Novelist, Haruki Murakami, likes to compare writing the works we all enjoy so much to running a marathon. He has run at least one a year for the last 30 years and has run the New York Marathon on at least three occasions.

For him running and writing seem interdependent. ‘Marathon running is not a sport for everyone, just as being a novelist isn’t a job for everyone’, Murakami says. ‘Nobody ever recommended or even suggested that I be a novelist—in fact, some tried to stop me. I simply had the idea to be one, and that’s what I did. People become runners because they’re meant to,’ he argues.

For many authors, not just Murakami, writing and running require a similar discipline and attitude. Mitsuyo Kakuta is another example of a well-known Japanese author who runs marathons. She started running marathons when she turned 40 and now runs two or three a year. Takuji Ichikawa is another example of a Japanese author who runs and also often writes about running. He ran the 800-metres competitively when he was a university student, and is on record as saying that running is an important part of his creative process.

-

- Olympic Narratives

W

hen Japan hosted the Olympic games for the first time in 1964 in Tokyo, it made sure that it was the first Olympics to broadcast the entire marathon live. The Tokyo Olympics created tremendous excitement and many new narratives about Japan, as well as all sorts of stories and myths in the country. The world came to Japan for the very first time. And the flagship event, the men’s marathon, was certainly a key highlight that many were waiting for.

Kokichi Tsuburaya (1940-1968) was the local marathon favourite. He ran a strong race entering the stadium in second position, in the very last athletics event of the Olympics, with the nation’s eyes fixed on him and a potential silver medal in the offing.

Sadly, he was overtaken on the final lap by Britain’s Basil Heatley, who somehow managed to find enough residual energy for a final sprint, and Tsuburaya finished third, something he never got over. Instead of being a proud winner of a bronze medal he became the man who lost his silver medal on the last lap with all of Japan watching. He killed himself less than four years later. His body was found with his bronze medal in his hand along with two suicide notes.

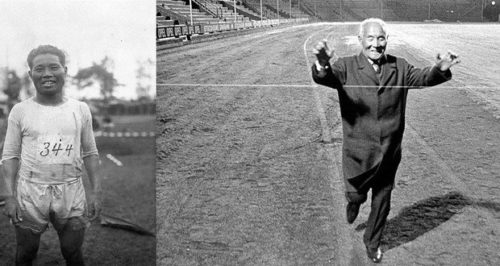

Shizo Kanakuri (1891-1983), who founded the Hakone Ekiden, holds one of the oddest Olympic marathon records. Kanakuri, a founding figure in Japanese marathon history, competed in the 1912 Stockholm Olympics.

Unexpected weather made it a particularly tough marathon, with many runners forced to drop out. Kanakuri, who had arrived in Stockholm after a three-day trip including the Trans-Siberian Railway, lost consciousness during the race.

A local family was kind enough to take care of him and he quietly returned to Japan unnoticed without informing the officials. He was thus technically classified as a ‘lost’ runner.

Shizo Kanakuri (1891-1983) in his youth and in later life. Photograph: Factrepublic.com

Shizo Kanakuri (1891-1983) in his youth and in later life. Photograph: Factrepublic.com‘It was a long trip,’ he remarked. ‘Along the way, I got married, had six children and 10 grandchildren.’

The first women’s marathon at an Olympics took place in 1984, at the Los Angeles Olympics. Since then Japanese women have participated and performed well, often better than the men.

In 2000, at the Sydney Olympics Naoko Takahashi set a new Olympic record for the marathon and become the first Japanese woman to win; not just a gold for the marathon, but for an Olympic track and field event. Four years later at the birthplace of the Olympics, in Greece in 2004, Muzuki Noguchi won the marathon, bringing home gold for Japan yet again.

In 2018, despite coming second, Yuta Shitara broke the Japanese men’s marathon record by completing the Tokyo Marathon in 2 hours 6 minutes and 11 seconds, a record that had been in place since 2002. Inevitably, expectations are growing for Olympic medals from both Japanese men and women in 2020.

No matter what medals Japan wins in the men’s and women’s marathon at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, the excitement and euphoria, as well as the current marathon running craze, may eventually die down. Unexpected future scenarios are possible, and new popular sports may emerge.

It’s something that the surrealist and science fiction author Yasutaka Tsutsui explored in his 1971 short story, Running Man. Tsutsui, who has an uncanny knack for imagining things that actually come to pass, subtly poked fun at the Olympics and much else in this story.

In this short story, set in the future, restaurants are automated and run by robots; marriages are arranged by computer-matching that analyses both physical and personality compatibility; and nobody is interested in long-distance running or the Olympics at all. Most have completely forgotten about them. Some don’t even know what the word means, and nobody or almost nobody runs.

Olympics still take place, but most people are lazy and uninterested in sports or competition, and many die young. Nobody really knows why someone would bother running a marathon. Nevertheless, one man decides to join the Olympic marathon, a race with only two other competitors, which takes him most of his life to complete.

He drops out half way after meeting a woman, and decides to start a family. But after his wife Yoko ends up in a nursing home, he decides to complete the race and once he does, he actually wins; but he isn’t treated to applause or a glorious medal ceremony, as nobody knows or cares. And unlike the case with the real Olympic runner Kanakuri who finally completed his marathon four years before Tsutsui wrote this short story, there were no television crews either; just a couple of officials working for the Olympic Organizing Committee Final Accounts Office.

-

- The Running Shoe becomes the Narrative

P

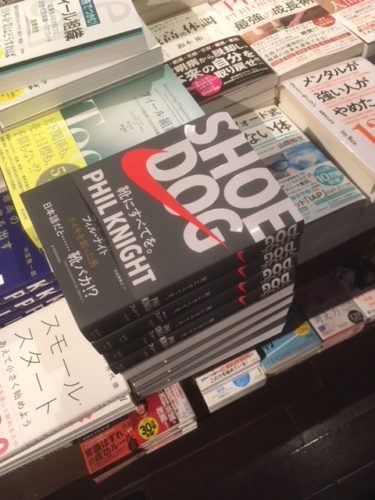

hil Knight, who was a runner in his University of Oregon days, famously visited Japan in 1962, having just graduated from the Stanford Graduate School of Business.  Mizuno running shoe. The Mizuno 1gd152045 WAVE EKIDEN10

Mizuno running shoe. The Mizuno 1gd152045 WAVE EKIDEN10 Japanese edition of Shoe Dog by Phil Knight on sale at a Tokyo bookshop. Photo: Red Circle Authors Limited.

Japanese edition of Shoe Dog by Phil Knight on sale at a Tokyo bookshop. Photo: Red Circle Authors Limited.When Knight returned from his graduation trip he set up Blue Ribbon Sports, which subsequently became Nike. And the rest, as they say, is history, which has been documented in his book Shoe Dog.

Today, Nike is the global market leader for sportswear and shoes. This was achieved with help from some people Knight headhunted from Onitsuka.

When it comes to sports shoes and sportswear, Nike has the largest market share in both the United States and Japan, and Knight is now one of the richest men in America.

Onitsuka still makes excellent shoes under the ASICS name, but in terms of sales, sits in joint third place behind Nike and Adidas with another Japanese brand, Mizuno. All of which reads a little like the story of Japan’s decline during what economists have called Japan’s lost decades since her economic bubble burst at the beginning of the nineties.

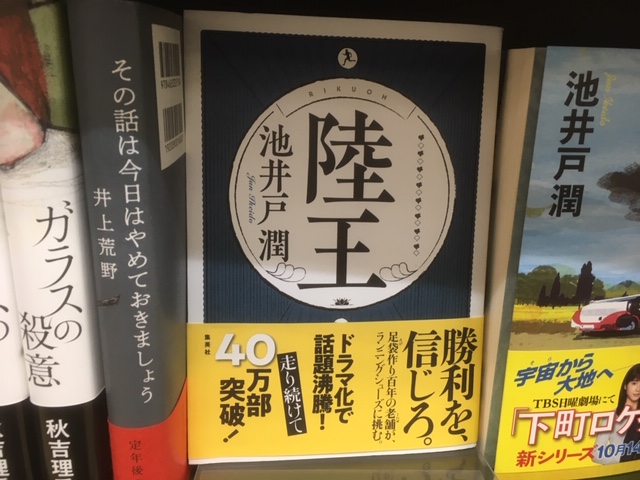

Jun Ikeido, a former banker turned management consultant then author, is known for business-themed novels, some of which depict Japanese businesses fighting back against impossible odds.

His bestselling novel Downtown Rocket tells the story of a small maker of engines in Tokyo who develops a highly sought-after patent forcing the firm to decide if they should license the patent to a major firm or build their own rocket. The book won Ikeido the prestigious Naoki Prize in 2011.

Land King, Rikuo, by Jun Ikeido, published by Shueisha in 2016, on sale at a Tokyo bookshop. According to the promotional book band the book has sold more than 400,000 copies. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.

Land King, Rikuo, by Jun Ikeido, published by Shueisha in 2016, on sale at a Tokyo bookshop. According to the promotional book band the book has sold more than 400,000 copies. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.This is an entertaining work of corporate fiction about a small Japanese company named Kohaze-ya that manufactures traditional Japanese socks known as tabi, taking on the American based global sporting goods market leader, Atlantis.

It is the story of a two-year tenacious marathon-like struggle to develop the best running shoe from scratch. Koichi Miyazawa, the fourth generation President of Kohaze-ya, stakes the firm’s future on this new shoe.

The story bears similarities to Kinky Boots, the 2005 British film and Broadway show, about a fourth-generation man trying to save his family-run shoe factory from closure by making high-heel boots for drag queens.

In Land King, Miyazawa recruits people to help him, including a ‘shoemeister’ from Atlantis, who is tired of the American giants’ relentless focus on profits; and a marathon runner, Hiroto Mogi, who was previously sponsored by Atlantis. Atlantis is obstructive, but with the help of ultra-light new material and a patented processing technology the Japanese underdog fights back.

Another interesting, but very different, example of a story about a former runner turned running shoe salesman is Haruki Murakami’s short story Kino from his collection Men Without Women. This story, which in typical Murakami fashion features a jazz bar, a cat and two snakes, can be read in English translation in The New Yorker.

-

- Meditations on Movement

M

any entertaining, eloquent and intelligent things have been written or said about marathons, running and reading. The American author George Saunders describes reading as ‘a form of prayer, a guided meditation that briefly makes us believe we’re someone else, disrupting the delusion that we’re permanent and at the centre of the universe.’

A running shoe on sale at a shop in Tokyo. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.

A running shoe on sale at a shop in Tokyo. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.‘Reading is an exercise,’ says the British author and Children’s Laureate Malorie Blackman ‘that involves walking in someone else’s shoes for a while.’

Even if that happens to be the shoes of a shoemeister. A good book, unlike long-distance running, is never about endurance, even if it has a departure and an arrival or is about a race.

Emil Zatopek (1922-2000), known as the ‘Czech-Locomotive’, who was the first man to win the triple, at the Helsinki Olympics in 1952 – the 5,000 metres, 10,000 metres and the marathon, which he won in a time of 2 hours 23 minutes 4 seconds, famously said: ‘if you want to run, run a mile. If you want to experience a different life, run a marathon’.

There are other options. If you don’t like running, pick up a book by one of Japan’s current cohort of award-winning authors and you will be assured to experience a different life, one that may still leave you breathless.

© Red Circle Authors Limited

2015 Tokyo Marathon - Japanese runners Photo: nakashi from Ichikawa, Chiba, JAPAN (Wikimedia)

2015 Tokyo Marathon - Japanese runners Photo: nakashi from Ichikawa, Chiba, JAPAN (Wikimedia)