Netsuke of Books, a Gourd, Fan and Box,18th century. Credit: Gift of Mrs. Russell Sage, 1910. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Netsuke of Books, a Gourd, Fan and Box,18th century. Credit: Gift of Mrs. Russell Sage, 1910. Metropolitan Museum of Art.reasured by emperors and clutched by royalty as status symbols, these multi-functional devices initially evolved from wooden sticks used for note taking and record keeping.

Subsequently, the arrival of paper helped transform this early form of ‘cool-tech’. The devices, known in Japan as Ogi, were a transformative technology in their own right, and provided much more than portable sophistication.

Over time, upgrades and enhancements turned the Ogi into highly fashionable handheld canvases that displayed art and poetry, as well as delightful and entertaining prose, allowing their proud owners to project sophistication, taste and wealth at a flick of the wrist, at home or on the go. And Japan’s literati loved them.

The Japanese folding fan was the must-have magical product, the IT device of its age.

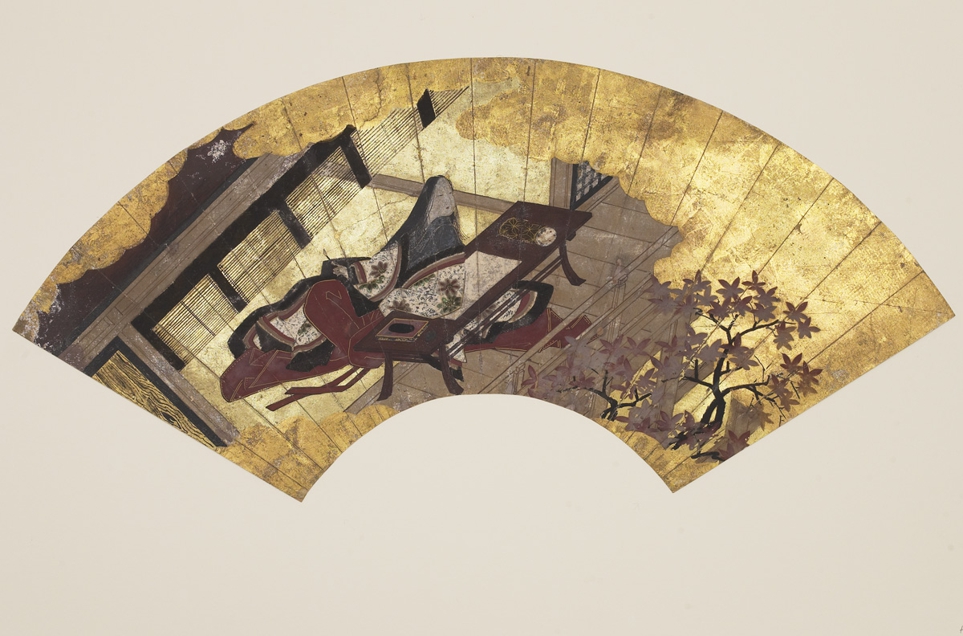

Fan exhibited at The Tale of Genji: The Impact of Women’s Voices on a Thousand Years of Romance in the Arts exhibition at the Honolulu Museum of Art. Anonymous Lady Murasaki Japan, Edo period (1603-1868), 17th century Fan; ink, color and gold on paper Gift of John Gregg Allerton, 1984 (5264.1). Credit: Honolulu Museum of Art.

Fan exhibited at The Tale of Genji: The Impact of Women’s Voices on a Thousand Years of Romance in the Arts exhibition at the Honolulu Museum of Art. Anonymous Lady Murasaki Japan, Edo period (1603-1868), 17th century Fan; ink, color and gold on paper Gift of John Gregg Allerton, 1984 (5264.1). Credit: Honolulu Museum of Art.-

- The unfolding of a handheld narrative

roadly, there are two types of traditional Japanese fan: fixed fans, called Uchiwa, and folding fans, Ogi. The origins of fixed rigid fans, which are still popular in Japan today, go far back to antiquity.

The Egyptian pharaohs and Chinese emperors used them to symbolise majesty and authority, as well as to keep cool. Beautiful examples were, for instance, found in Tutankhamun’s tomb.

However, the foldable fan, according to most experts and connoisseurs, is a Japanese invention, a typical recreation and repurposing of imported know-how from China, that was opportunistically re-exported with lasting global repercussions.

Mokkan from Nara period (710-784). Image: factsanddetails.com.

Mokkan from Nara period (710-784). Image: factsanddetails.com.In pre-modern Japan, in the Asuka (552-710) and Nara (710-784) periods, the nation’s aristocrats, bureaucrats and rulers used portable narrow strips of wood, called mokkan, as notebooks.

The folding fan is thought to have developed from these and was then upgraded with a brand new display technology, thanks to paper, after its arrival in Japan (also from China).

Tens of thousands of mokkan have been discovered to the delight of archaeologists and scholars of ancient texts, some describing crown princes, others emperors, and some religious texts.

However, many of these sticks actually had much more mundane roles functioning like the metadata tags of our age, labeling and documenting items, creating records of ownership, formalising tax rates and recording regulations.

Mokkan were used in other countries too. In Korea and China for instance. Nevertheless, carrying around bundles of small-inscribed wooden sticks was not ideal even in pre-modern Japan. This burden of bureaucracy was too much even for Japan’s bureaucrats of old.

Rivets were attached at their base binding the strips together into expandable, fan-like, readable and portable collections. And at some point these developed into foldable wooden fans.

Evidence of their use can in fact be traced further back still. A folding cypress fan inscribed with the date 877 made from wooden strips was discovered in 1959 inside an arm of a Buddhist statue at one of Japan’s oldest temples in Kyoto. This ancient fan is decorated with pictures and inscribed with text as well as a date. Archeologists have also found fan-shaped wooden strips in Japan dating back to as early as 747.

The arrival in Japan of paper making techniques in 610, which was initially a highly converted technology before paper was commoditised, predates these fans.

Legend has it that in the reign of Emperor Tenji (626-672), Japan’s 38themperor, the discovery of a dead bat with burnt wings inspired a Japanese craftsman to make a prototype that was in fact the world’s first functioning folding fan.

Still it is hard to pinpoint exactly when these early wooden folding fans, known as hiogi, were developed and then upgraded into the beautiful folding paper fans Japan is now famous for.

Fans in Japan have many names, the folding variety, are sometimes actually referred to as kawahoriogi, bat-fans, due to their resemblance to the open wings of a bat; as well as hiogi (wooden fans often made of cypress), kamiogi (paper or silk fans) or the generic ogiand sensu (folding fan), while fixed fans that pre-date folding fans are known as uchiwa (fixed or round fans).

-

- Literature fans

Despite this ‘poetic’ and somewhat backhanded compliment, references to fans in the canon of Japanese literature (in poems, dictionaries and manuscripts) can be found in some of Japan’s oldest and most important literary works long before the birth of this famous Chinese poet, and the start of China’s Song Dynasty (960-1279).

Fans appear in Japan’s oldest poetry anthology, Manyoshu, The Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves, a collection of thousands of poems compiled in 759 that provided the inspiration for the name of Japan’s current imperial age, Reiwa, that started on 1 May 2019.

Interestingly, this collection was compiled during Japan’s Nara period (710-794) when Japan’s capital was located in Nara; and the era when many of the ancient mokkan found so far date from. Most now believe this is when the first hiogi were made.

Fans also appear in early Japanese dictionaries and folding paper fans feature in Japan’s oldest novel The Tale of Genji and in a famous scene in Heike Monogatari, an epic account of the battles between two Japanese clans, when the warrior Nasu no Yoichi (1169-1232) riding his horse shoots a fan off a pool on a swaying ship with a single shot from his bow and arrow.

Nonetheless, experts believe that the first Japanese paper folding fan was probably created in the middle to late eighth century close to the start of Japan’s Heian period (794-1185) when the Japanese capital had moved and was based in what has now become Kyoto.

Fan-shaped Booklet of the Lotus Sutra,Vol. 1 (National Treasure) Heian period, 12th century Shitenno-ji Temple, Osaka. Credit: Suntory Museum of Art.

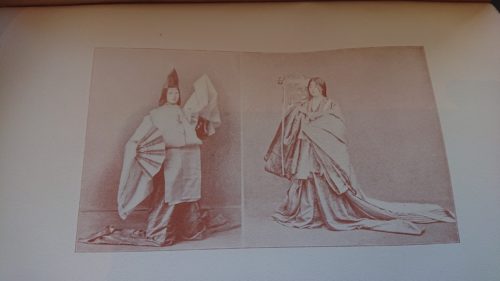

Fan-shaped Booklet of the Lotus Sutra,Vol. 1 (National Treasure) Heian period, 12th century Shitenno-ji Temple, Osaka. Credit: Suntory Museum of Art.As fan fashions developed in Kyoto, they quickly became part of aristocratic dress codes, with wooden fans becoming part of winter collections, and paper fans the summer wardrobes of Japanese noblemen and women.

Images of ‘Nobelman of Heian Epoch’ from multi-volume reference work, Japan and China, by Captain F. Brinkley (1841-1912), Editor of The Japan Mail and special correspondent for The Times, published in 1903. Photogragh: Red Circle Authors Limited.

Images of ‘Nobelman of Heian Epoch’ from multi-volume reference work, Japan and China, by Captain F. Brinkley (1841-1912), Editor of The Japan Mail and special correspondent for The Times, published in 1903. Photogragh: Red Circle Authors Limited.-

- Miniature portable museums

Alongside Japanese screens and swords, fans became highly desirable popular must-have Japanese products in countries like China, as well as in Japan, and further afield.

Fans Floating on a Stream (Important Cultural Property; four panels from the north side of the first room in the Shogunate bathing rooms at Nagoya Castle) Edo period, ca. 1633 Nagoya Castle Office. Credit: Suntory Museum of Art.

Fans Floating on a Stream (Important Cultural Property; four panels from the north side of the first room in the Shogunate bathing rooms at Nagoya Castle) Edo period, ca. 1633 Nagoya Castle Office. Credit: Suntory Museum of Art.Fans have and are still used as ritual offerings to the gods and tools to summon them. They have at times become substitutes for swords. And they regularly appear, sometimes discreetly and at times overtly, at important milestones in the lives of most Japanese people. When, for example, celebrating turning three, five, seven and 60 or getting married.

-

- Fans, commercial art and storytelling

As a result, fans became widely available in Japan allowing many, regardless of their status, to buy and collect commercial art that often included palm-sized portable prose and poetry, probably for the very first time.

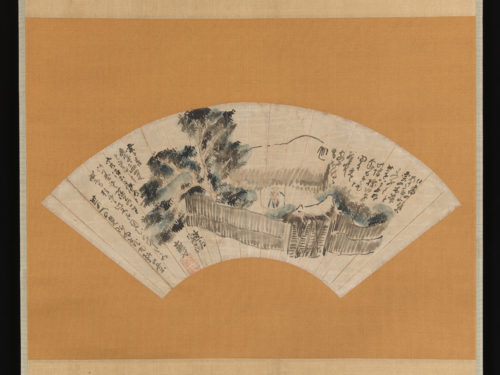

Folding fan mounted as a hanging scroll; ink and color on paper. Scene from The Narrow Road to the Deep North (Oku no hosomichi) by Matsuo Basho (1644-1694), ca. 1780. Credit: Mary Griggs Burke Collection, Gift of the Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation, 2015. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Folding fan mounted as a hanging scroll; ink and color on paper. Scene from The Narrow Road to the Deep North (Oku no hosomichi) by Matsuo Basho (1644-1694), ca. 1780. Credit: Mary Griggs Burke Collection, Gift of the Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation, 2015. Metropolitan Museum of Art.Sometimes with cryptically shortened poems encouraging admirers to guess the origins and if successful show-off their knowledge of literature when a fan was opened and the prose revealed.

Japan’s rich world of storytelling has a long history of combing art, illustrations and narrative prose, and the development of paper folding fans gave the creative arts new impetus – creating new demand and delighting Japanese literati as well as the general public.

Designs developed to include, for instance, watermarks, tassels and carved ribs and fans were made for men and women of all ages and for all the seasons.

By the time of Japan’s Edo period (1603-1868) there was a fully-fledged highly creative fan-making boom and an innovative industry to support it.

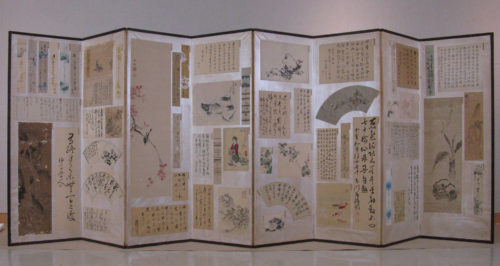

Collection of fans, paintings and calligraphy by Literati of Iga Ueno, early 19th century. Credit: Gift of Akiko Kobayashi Bowers, 1989. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Collection of fans, paintings and calligraphy by Literati of Iga Ueno, early 19th century. Credit: Gift of Akiko Kobayashi Bowers, 1989. Metropolitan Museum of Art.In fact, almost all of Japan’s established artists jumped on the fan painting and making bandwagon. Fans, despite their perishable nature, became a precious creative platform that couldn’t be ignored by struggling or even established artists.

Fans, which were easy to monetise became the mass-market canvas of choice creating a platform for artists to distribute and sell their creativity, a phenomenon that ended up as an inescapable trend that even many of France’s famous impressionist painters would eventually feel compelled to follow years later.

-

- The pursuit of the cool: posing with fans

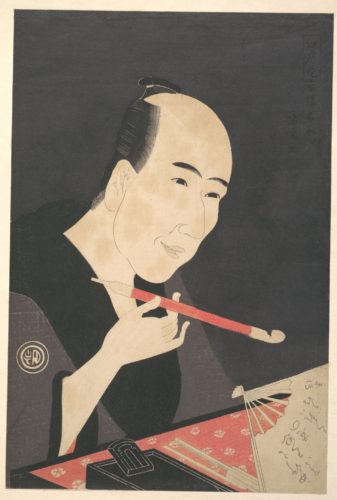

The writer Santo Kyoden (1761-1816) also known as Kitao Masanobu, ca. 1795. Poem inscribed on the fan: ‘Priest Saigyo has not seen the flourishing gay district yet! (Priest Saigyo would not have renounced the world if he had seen the flourishing gay district!)’ Credit: The Howard Mansfield Collection. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The writer Santo Kyoden (1761-1816) also known as Kitao Masanobu, ca. 1795. Poem inscribed on the fan: ‘Priest Saigyo has not seen the flourishing gay district yet! (Priest Saigyo would not have renounced the world if he had seen the flourishing gay district!)’ Credit: The Howard Mansfield Collection. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.They feature at weddings: at tea ceremonies; in traditional games such as Tousenkyo; in Japanese theatre; in Rakugo, traditional Japanese comedy, as a prop used by comedians; as well as at important national events including, for instance, the official events that surrounded the new emperor’s enthronement – during which all female members of the Imperial family clutched specially designed folding Japanese fans.

This fondness for fans, their power to make a dramatic point or enhance gestures, and the benefit of posing with them, especially the handheld folding variety is not just limited to Japan and its elite.

Queen Elizabeth I (1533-1603) is perhaps one of the best known early adopters of fan-power. She enjoyed clutching and collecting folding fans and had a collection of 27 at the end of her life.

Fans arrived late in her reign as gifts from afar from individuals like Sir Francis Drake (1563-1596), the first Englishman to circumnavigate the world.

Queen Elizabeth employed these fans when power dressing for some of her many portraits that were designed to project her status and authority.

Queen Elizabeth I (The Ditchley portrait) by Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger. Credit: NPG 2561: © National Portrait Gallery, London

Queen Elizabeth I (The Ditchley portrait) by Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger. Credit: NPG 2561: © National Portrait Gallery, LondonIn it Queen Elizabeth can be seen standing on a globe of the world with her feet on Oxfordshire, while holding a Japanese-style folding fan in her right hand. This is, in fact one of the oldest European paintings featuring a folding fan.

The image is an important one because it clearly shows that folding fans and the perceived benefit and importance of posing with them had now reached the royal courts of Europe.

The only surviving cord and ribbon Elizabethan embroidered folding fan, from the 16th century (circa 1590s), on display at The Fan Museum London. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.

The only surviving cord and ribbon Elizabethan embroidered folding fan, from the 16th century (circa 1590s), on display at The Fan Museum London. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.British trade with Asia really only took off following the establishment of the East India Company in 1600, which helped spread trade and British influence three years before the Queen’s death. And the East Indian Company is known to have imported lots of fans mostly from China during this period.

The Queen’s 1592 folding fan portrait was painted before this and long before the permanent Dutch trading post in Nagasaki opened in 1641.

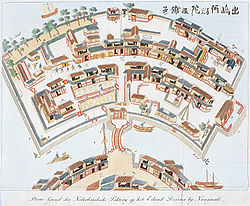

This trading post known as Dejima (Exit Island) was actually an artificial island created especially to house foreigners at a safe and controlled distance from the Japanese mainland. It was, of course, shaped like a fan.

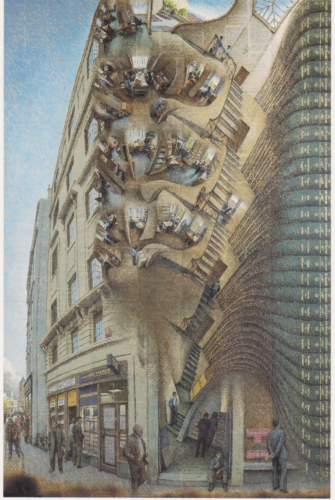

An imagined bird’s-eye view of Dejima’s (copied from a woodblock print by Toshimaya Bunjiemon of 1780 and published in Isaac Titsingh’s (1745-1812) Bijzonderheden over Japan (1824/25). Credit: Wikipedia

An imagined bird’s-eye view of Dejima’s (copied from a woodblock print by Toshimaya Bunjiemon of 1780 and published in Isaac Titsingh’s (1745-1812) Bijzonderheden over Japan (1824/25). Credit: Wikipedia-

- Fan fever: an international boom

However, nine years after Commodore Perry (1794-1858) and his famous black ships forced Japan’s markets open again in 1853 with dramatic consequences, the nation’s artists and their fans were more than ready for their international debut.

Japanese products and art were initially shown at The International Exhibition in London in 1862, one of the very first major public shows that included Japanese art.

This was followed by a series of highly influential events in Paris, which had historically been a major centre for fan making, including the Exposition Universelle (World Fair).

Bamboo and Rocks by a Stream,1832, by Takaku Aigai (1797-1843). Credit: The Harry G. C. Packard Collection of Asian Art, Gift of Harry G. C. Packard. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Bamboo and Rocks by a Stream,1832, by Takaku Aigai (1797-1843). Credit: The Harry G. C. Packard Collection of Asian Art, Gift of Harry G. C. Packard. Metropolitan Museum of Art.By 1872, a French art critic had invented a new label helping define and brand the growing obsession with Japan and the Japanese arts: Japonisme.

This would later prompt Oscar Wild (1854-1900) to caustically and famously write in response to what he saw as aesthetic fancy inspired by French intellectuals and artists: “The whole of Japan is a pure invention. There is no such country, there are no such people.”

-

- Art in life: enjoyed anywhere by anyone

Photograph of a young Albert Einstein (1879-1955) and his sister Maja (Maria) holding an oriental Japanese-style umbrella. At the height of Japonisme in the 1880-90s all things Japanese were popular including fans, kimonos and umbrellas. Photo: Red Circle Authors Limited.

Photograph of a young Albert Einstein (1879-1955) and his sister Maja (Maria) holding an oriental Japanese-style umbrella. At the height of Japonisme in the 1880-90s all things Japanese were popular including fans, kimonos and umbrellas. Photo: Red Circle Authors Limited.Their price points helped. The fact, that they were probably the lowest cost Japanese items one could attain also made them exceptionally attractive to Western eyes. These highly desirable multi-purpose handheld devices; these pocket-sized galleries of Japonisme were both cutting-edge and cool, while being very affordable.

It seems hard to imagine today, but this had wide reaching impact. The iconography from Japanese art and fans started being incorporated into European art and design. They would eventually famously influence the likes of Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) and Henri Matisse (1869-1954).

At the fourth Impressionist exhibition in Paris in 1879, Edgar Degas (1834-1917) reportedly wanted to include a room devoted entirely to fans painted by him, Camille Pissarro (1830-1903) and other impressionists. This didn’t in fact happen, but 21 fans by him and Pissarro and others were exhibited.

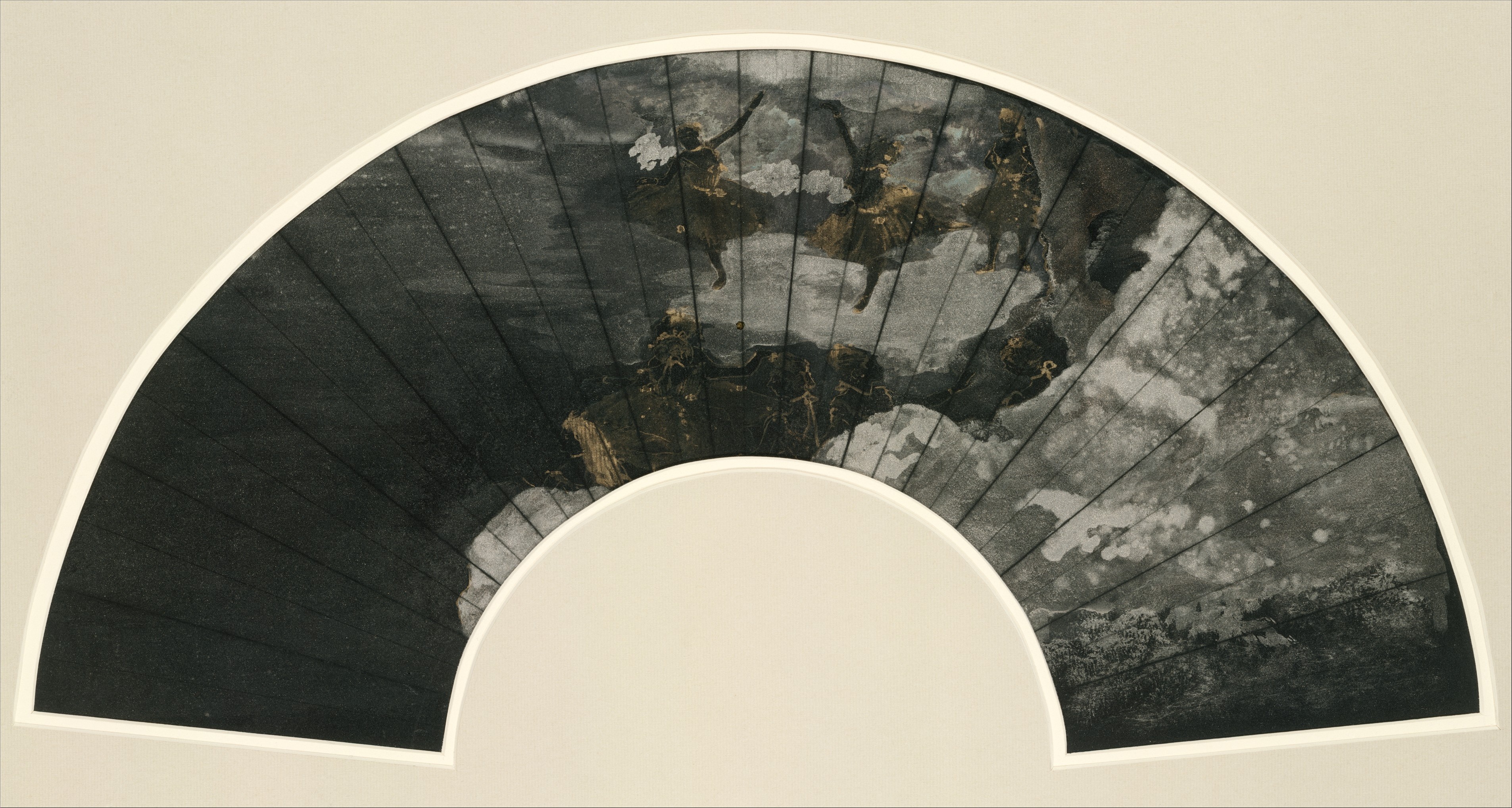

Fan Mount: The Ballet,1879 by Edgar Degas (1834-1917) . ‘Painted in monochrome on a black ground, this fan evokes the metallic luster of Japanese lacquers’. Credit: H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Fan Mount: The Ballet,1879 by Edgar Degas (1834-1917) . ‘Painted in monochrome on a black ground, this fan evokes the metallic luster of Japanese lacquers’. Credit: H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929. Metropolitan Museum of Art.One French art critic dubbed it: “une epidémie d’éventails” (a fan epidemic). And in a similar manner to Japan’s Edo period artists, many of the French impressionists found that painted fans were one of the easiest forms of commercial art from which to earn a living.

-

- From fanology to emoji: are we now all fans of Japan?

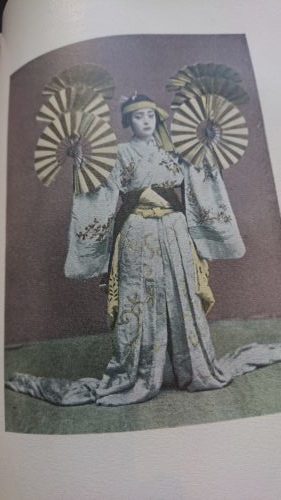

Image of ‘A Dancing Girl’ from volume IV of multi-volume reference work, Japan and China, by Captain F. Brinkley (1841-1912), published in 1904. Photogragh: Red Circle Authors Limited.

Image of ‘A Dancing Girl’ from volume IV of multi-volume reference work, Japan and China, by Captain F. Brinkley (1841-1912), published in 1904. Photogragh: Red Circle Authors Limited.Perhaps the delayed international release is one of the factors behind the success. But whatever the reason, when they finally arrived in Europe, fans from Japan started selling in the millions.

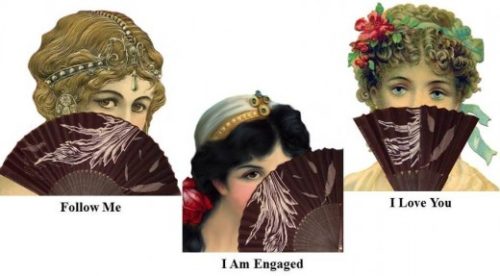

A new culture emerged that included its own special messaging, dubbed fanology, the emoji of the Victorian age.

Curiously, the ubiquitous emoji of our digital age, unlike fanology, is another Japanese reinvention. They emerged on Japanese mobile phones in 1997, thanks this time to Shigetaka Kurita, before they arrived on phones and devices around the world.

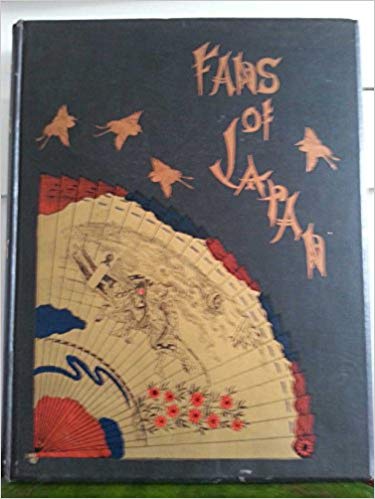

Salwey, Charlotte M. Fans of Japan. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner, & Co. Ltd., 1894. First Edition.

Salwey, Charlotte M. Fans of Japan. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner, & Co. Ltd., 1894. First Edition.Victorian fan salesmen, including the French master fan maker Jean-Pierre Duvelleroy (1802-1889), produced fanology guides to show women how to send out messages at a discreet distance using their fans that meant: Follow Me; I Love You; or I Am engaged.

Publishers also got in on the act and books about Japanese fans also started appearing in English such as Charlotte Salwet’s 1894 book, Fans of Japan, which included colour images and illustrations.

Interestingly, this book credits Japan as the nation that invented the folding fan with its ‘bamboo frame’. Many books have followed, somewhat breezily, in its wake.

Duvelleroy’s Fan Language from the 19th century. Image: Annabellee36.

Duvelleroy’s Fan Language from the 19th century. Image: Annabellee36.-

- A new industry and a new high for fans

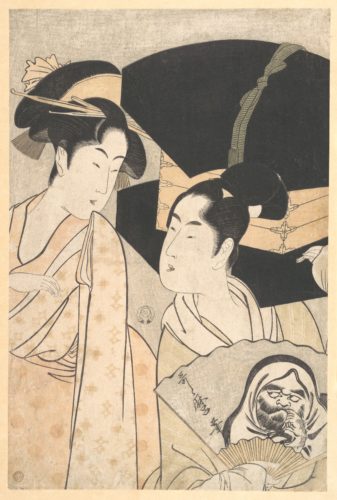

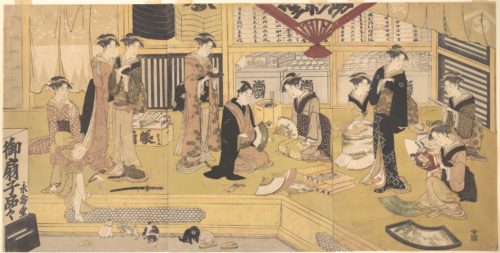

Fan Vendor, 1790s Kitagawa Utamaro (1753-1806).The male vendor in this image is showing a fan painted with the face of the Zen master Daruma to a beautiful young woman. Credit: Gift of Estate of Samuel Isham, 1914. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Fan Vendor, 1790s Kitagawa Utamaro (1753-1806).The male vendor in this image is showing a fan painted with the face of the Zen master Daruma to a beautiful young woman. Credit: Gift of Estate of Samuel Isham, 1914. Metropolitan Museum of Art.Remarkably, some shops, which were first opened in Kyoto in the 17th century, are still in business today. The majority of trends are fickle, but fans in Japan, have shown persistence and true staying power.

Europe also had its own fan industry long before the arrival of Japonisme and direct Japanese imports.

In 1670, just over a hundred years after Queen Elizabeth I posed for her famous portrait, broadcasting her power and wealth, a group of fan-making businesses in London petitioned the nation’s parliament to introduce regulations to protect the London market from outside competition.

This led to the granting of a royal charter by Queen Anne (1665-1714) and the foundation of a specialist fan Livery Company in 1709, The Worshipful Company of Fan Makers.

This probably marked the height of fan making in England, and as in Japan’s Edo period, English fans of the period also reflected life.

Designs included everything from religious and classical subjects to cartoons and British satire and humour.

The Mieido Fan Shop,ca. 1785–93. Credit: The Howard Mansfield Collection. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Mieido Fan Shop,ca. 1785–93. Credit: The Howard Mansfield Collection. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.-

- Foldable cool: a lasting motif

ong before the Japanese government had a modern branding strategy and its Cool Japan programme for promoting Japan as a cultural superpower, Japanese folding fans were cooling and charming the world. And perhaps it is not surprising that Japan is now still at times referred to as the country or land of fans.

Many associate the words fan and Japan in the same breath. The words regularly appear in popular culture, journalism, lyrics and imagery, making the fan one of the many cultural motifs and emblems that seem to personify, for better or worse, the land of the rising sun.

In the 1950s, for instance, the signature song of the Broadway musical Can-Can, which was a major hit in London and New York, contained the following lyric:

Twill be so easy for you.

If a lady in Iran can,

If a shady African can,

If a Jap with a slap of her fan can,

Baby, you can can-can too.

The musical is about showgirls in Montmartre’s dance-clubs in Paris in 1890s, a period when Japonisme was already peaking.

Many headline and caption writers have and still make similar associations, but perhaps a more appropriate and politically correct example of a lyric with this word association is the song (I’ll Never Be) Your Maggie May by the American singer-songwriter Suzanne Vega:

be like those ladies in Japan

rather paint myself a face

conjure up some grace

or be the eyes behind a fan

This, as well as a Japanese fan being the favoured accessory of the likes of the designer Karl Lagerfield (1933-2019), has no doubt helped put fans high up on the shopping lists of the millions of tourists who now visit Japan every year. This portable device is still an object of desire today.Like their creative predecessors from the Edo period, today’s Japanese fan-sellers have developed new marketing techniques that are right for the times.

YouTube videos now provide instructions on how to use a fan properly and English language manga-style instructional sheets are available for children.

-

- A visible hand with a folding future?

And displaying and creating hands-on exciting imagery that can be easily shared with a click or swipe of the finger, as opposed to a flick of the wrist, is as important as ever.

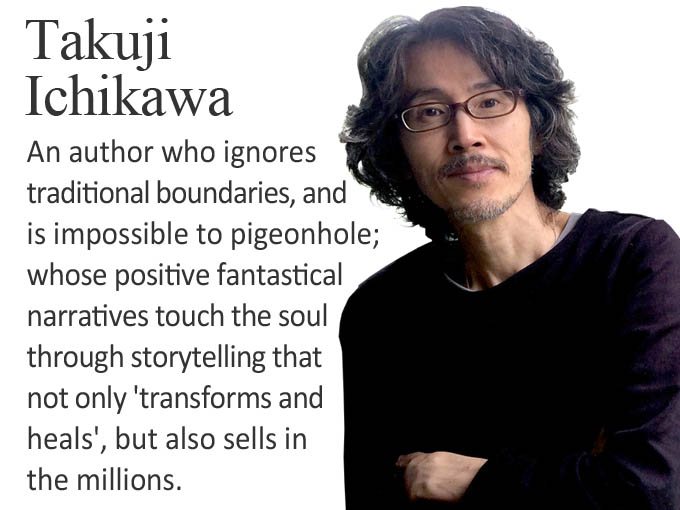

Initially, it was cell phones and now it is a generation of smartphones that have led the charge. And storytelling, in Japan at least, has again been part of this. Following the long tradition of writing on and for handheld devices, it is perhaps not surprising that the world’s first cell phone novel, keitai shosetsu, Deep Love, published in 2003 was Japanese.

Written by a 30-year-old Japanese man, it’s a gritty young-adult novel about a girl who turns to prostitution to pay for her boyfriend’s heart surgery, and dies herself after contracting AIDS.

Following its success, authors and publishers jumped on this trend quickly and by 2007 half of the top ten best selling fiction titles in Japan originated as ketai shosetsu. This publishing boom is, however, now over.

Nevertheless, new portable devices are already in development designed to exploit the next generation of wireless technologies and engineers are experimenting with folding screens with some success.

A new generation of portable canvases exploiting fan-like designs that blend and display exciting new content may be just around the corner.

It may seem fantastic, but could this be the chance, for Japan and its creative storytellers and designers, to become international trendsetters once again? Now that would really generate an opportunity for the fans of Japan.

Fans at Kotoden Takamatsu-Chikko Train Station. Credit: Wei-Te Wong. Wikimedia/Creative Commons

(https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2017-04 04_tickets_at_Kotoden_Takamatsu-Chikko_Train_Station.jpg)

Fans at Kotoden Takamatsu-Chikko Train Station. Credit: Wei-Te Wong. Wikimedia/Creative Commons

(https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2017-04 04_tickets_at_Kotoden_Takamatsu-Chikko_Train_Station.jpg)