Japanese novels in French translation on display at a bookshop in Montreux, Switzerland. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.

Japanese novels in French translation on display at a bookshop in Montreux, Switzerland. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.A quick analysis of English-language book review and selling websites show that Haruki Murakami dominates reading lists; followed by contemporary Japanese crime writers such as Natsuo Kirino, and Keigo Higashino both of whom are also very popular across Asia.

The global success of mass-market Scandinavian crime fiction, including Stieg Larsson, is said to be one of the drivers behind this trend, but other factors are at play. Globally connected digital youth, who are more open minded about authors with unfamiliar names and other cultures, is another: as are government programs to project and promote creative industries.

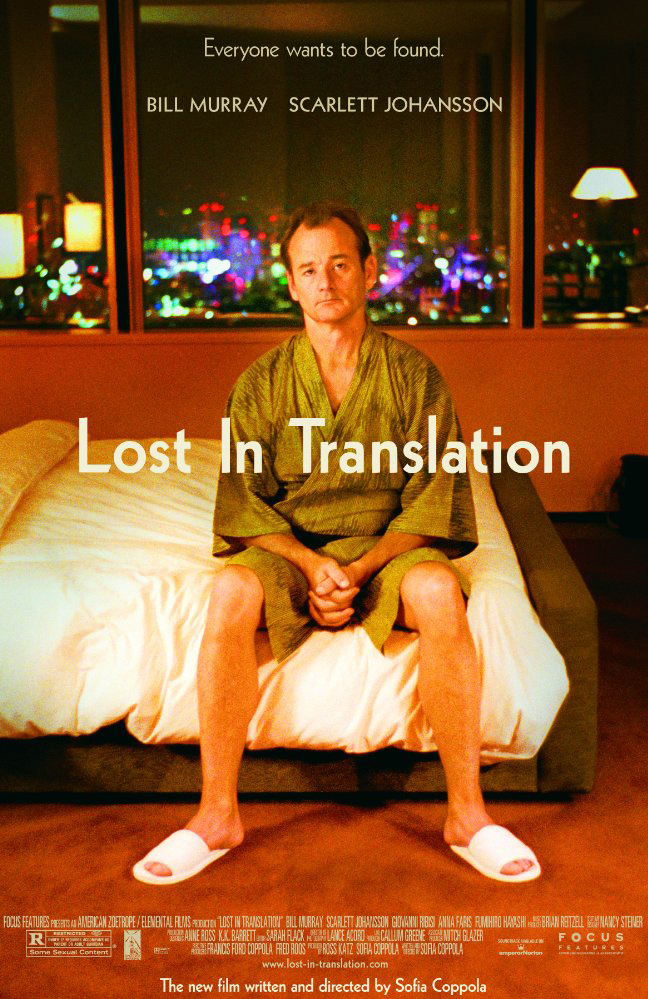

Film poster of Lost In Translation, Directed by Sofia Coppola. Image: Wikipedia/Focus Features.

Film poster of Lost In Translation, Directed by Sofia Coppola. Image: Wikipedia/Focus Features.Haruki Murakami whose works have been published in 50 languages, and Banana Yoshimoto who was first published internationally outside Japan in Italian, have aroused a new generation of international readers to compelling storytelling that Japanese readers have been enjoying quietly for decades.

Japanese non-fiction titles are also playing a major role in highlighting what is available for publication with titles like Marie Kondo’s international bestseller, The Life Changing Magic of Tidying Up.

More titles than ever before can now be found in Chinese, Russian, German, Italian, French, Thai, Spanish and other languages, but despite these trends only 3 percent of books published in the United States and the United Kingdom are translations and some of the most recent Japanese international publishing success stories started with a translation into French or Italian before creating a domino effected leading to editions in multiple languages.

The Guest Cat, by Takashi Hiraide: published in French; then English; then more widely, is a very good example of this. It came full circle as international acclaim generated curiosity in Japan and further local demand. In Russia, where there is a growing interest in Japanese culture and literature around 10 percent of published titles are translations, while the figure in China is around 7 percent.

As well as contemporary writers, the classics; by Junichio Tanizaki, Yasunari Kawabata, Kobo Abe, Shusaku Endo, and Soseki Natsume often appear on English language book sites. Interestingly, the name Kenzaburo Oe, one of only two Japanese winners of the Nobel Prize for literature alongside Kawabata, does not often pop up. Reading lists such as The Daily Telegraph’s 10 Best Asian Novels of All Time, often feature Japanese authors and titles: re-enforcing the phenomenon and creating demand. Rashomon by Ryunosuke Akutagawa, The Wind-Up Bird Chronicles by Murakami Haruki, Spring Snow by Yukio Mishima are listed in the newspaper’s latest top ten.

the classics;

by Junichio Tanizaki, Yasunari Kawabata, Kobo Abe, Shusaku Endo, and Soseki Netsume often appear

In 2014, Granta, a British publication founded in 1889 known for publishing nobel laureates, debut novelists and other forms of brilliant writing, joined this growing trend with the release of a special issue which it published simultaneously in English and Japanese. It contained contributions from: Yoko Ogawa, Toshiki Okada, Mitsuyo Kakuta, Kyoko Nakajima and others.

Authors of light novels (raito noberu), which generally target manga reading high-school students with short attention spans, are also starting to appear within Amazon’s ranking lists. These include: Fujino Omori, and Reki Kawahara who have written titles such as: Is it Wrong to Pick Up Girls in a Dungeon? and Sword Art Online.

The generation who are growing up with manga, and anime are starting to read light novels and are expected to subsequently start reading Japanese literature in other forms and formats, as their interests develop and evolve. This is already happening across Asia. Translation requests from Korean and Chinese publishers are now filed as soon as new title information is released; something that the traditional domestically-focused Japanese publishing industry is slowly trying to adapt to.

Another trend that is having a major impact on demand is tourism. Inbound tourists to Japan surpassed outbound tourists for the first time in 2015: reaching just under 20 million. Many tourists come back. Currently, Hong Kong and Taiwan have the highest repeater ratios running at an amazing 85-82%, followed by Thailand, Philippines, Malaysia and Singapore at 60-65%. Interestingly, publishers in some of these countries have increased the number of books by Japanese authors they publish in translation.

The next cluster of countries with high repeater ratios include: France, United States, United Kingdom and Canada with ratios of 60-55%. France is already an important market for translated Japanese fiction. China has the largest number of repeaters, but its repeater ratio though high is 43%; slightly higher than South Korea, which is also a large source of visitors.

Japanese crime fiction is particularly popular in China. Gruesome tales showing the dark side of Japan tend to appeal. Soji Shimada, author of The Tokyo Zodiac Murders, the only title of his around 50 that has been published in English, is very popular. One of his books The Edge of Reason is being adapted for film in China by Densen International Media. The story revolves around a 19 year-old-man who falls in love with the women who killed his father in a road accident.

Other Japanese crime writers popular in China include Keigo Higashino and Kotaro Isaka, whose titles are also being adapted for film in China. Chinese tourists visiting Japan, in a similar manner to how Sherlock Holmes fans visit Baker Street and other locations in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s books, are starting to plan where they go in Japan based on scenes in books and the preferences of their favorite fictional Japanese detectives.

With the Rugby World Cup taking place in Tokyo in 2019 and the Olympics the following year in 2020 awareness of all things Japanese will increase as will demand for Japan’s cultural exports and Japan as a tourist destination. The Japanese government is trying to harness these established trends to project Japanese Soft Power and turn the country into a so-called ‘Cultural Super-Power’. With around 80,000 new titles published each year and a long history of talented creative writers – many of who have yet to be read or discovered outside Japan – Japanese literature has a major role to play.

Tokyo Tower, the second tallest structure ( 332.9 meters) in Japan after Tokyo Skytree, which is nearly twice as tall, viewed from Zojoji Temple. The Temple was moved to its current location in central Tokyo by Ieyasu Tokugawa in 1598. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.

Tokyo Tower, the second tallest structure ( 332.9 meters) in Japan after Tokyo Skytree, which is nearly twice as tall, viewed from Zojoji Temple. The Temple was moved to its current location in central Tokyo by Ieyasu Tokugawa in 1598. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.