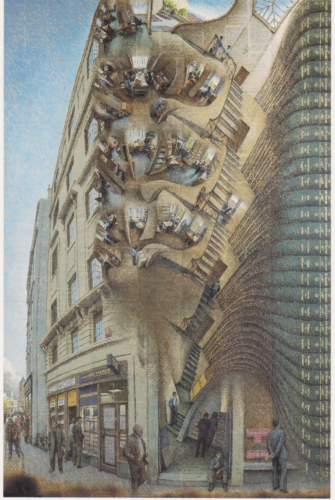

The office of The Dictionary of Art (TDA) on the Strand in London, at time of its publication, painted by Julian Bell (he is the figure at the bottom of the stairs). Image: Ian Jacobs

The office of The Dictionary of Art (TDA) on the Strand in London, at time of its publication, painted by Julian Bell (he is the figure at the bottom of the stairs). Image: Ian JacobsI

learned the art of reference book selling in US in the late 1970s. Macmillan was the publisher since 1979 of Sir George Grove’s (1820-1900) Dictionary of Music and Musicians, the Bible of all musicians and musicologists. We sold The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians to libraries, orchestras, music businesses and private individuals.

The tools of the trade were direct mail, telesales and book displays at conventions. We had very little to do with booksellers or distributors. Selling reference was very much a direct sales business.

We spoke directly to our end customers and understood their needs. This was invaluable intelligence for expanding sales, and for future editions and developing new reference books.

In the 1990s, as we prepared to publish The Dictionary of Art (known in Macmillan as TDA) in 34 volumes, I was asked to investigate new ways of selling TDA in Japan.

I soon learned that this was a very different world from the US. TDA was written by some 6,300 scholars worldwide and employed an expert staff of about 100 art historians.

With the help of our editorial adviser, the eminent scholar of Japanese painting Professor Akiyama (1918-2009), we enlisted Japan’s finest scholars of art, architecture, design and archaeology to produce the most comprehensive coverage yet published in English of Japanese art.

-

- The Mysteries of the Japanese Imported Book System

W

hen Macmillan published The New Grove in 1980, we negotiated exclusive Japanese rights to Maruzen. Maruzen bought a large quantity, added the traditional Japanese mark-up, and from then on sales in Japan were a complete mystery. Foreign publishers had very little choice.  The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians

The New Grove Dictionary of Music and MusiciansJapan was an important market for academic reference publishers. Universities were numerous and had large library budgets. Moreover, professors often had their own book budget in addition. The puzzle was how to maximize sales and develop relationships with our end customers.

-

- Challenging the Rules with The Dictionary of Art

I

n 1994 I flew to Tokyo for my first experience of Japan, armed with the BBC’s Get by in Japanese, and installed myself at the Hilltop Hotel, a favourite with publishers and literary folk.  Cover of Get by in Japanese published by the BBC

Cover of Get by in Japanese published by the BBCWe would brief the Kinokuniya sales teams but would also ourselves carry out direct mailing, telesales and other advertising and promotion.

We wanted to avoid the Japanese mark-up and to agree a Japanese price of 1 million Yen, roughly equivalent to the price in US dollars and Pounds Sterling.

Mr Takai asked many questions and agreed to consider my proposal.

As soon as I left, he telephoned his opposite number at Maruzen to ask if I had visited there and what proposal I had made. Competition in Japan did not work in the same way as it did in the US. After some consideration, Mr Takai agreed to our proposal.

-

- Adapting US Direct Sales Methods to Japan

T

he next step was to hire a marketing manager and develop a detailed plan. We employed Naoko Matsumoto, a fluent English-speaker who worked with me to adapt our US and UK marketing materials and plans for use in Japan.

We produced brochures, a Japanese version of our promotional video, and developed lists of libraries and other potential customers for a telesales campaign.

-

- Building Alliances

T

he first step was to develop alliances to help us reach as wide a market as possible. Professor Akiyama, was the key to the academic market. Akiyama-sensei was the son-in-law of a famous Japanese artist Seison Maeda (1885-1977), and his prestige guaranteed us a meeting with any professor we needed to meet. We held frequent parties: I learned that parties are an important part of networking in Japan.

Meanwhile, Naoko made appointments to meet museum directors, art gallery owners, art critics, editors of art and cultural magazines.

One visit was to a magnificent ceramics museum in Osaka. After tea and a chat with the director, he gave us a tour of the highlights of his collection. I asked Naoko why the museum was so empty of visitors. She replied that it was closed for a public holiday and that the director had come to work specially to show me his museum.

As we finished a visit to a Ginza art gallery, managed by an elegant Japanese lady, I stopped to admire a Warhol portrait of a young woman. As I studied the work I realized that I had just met its sitter.

-

- On the Road in Tokyo, Kyoto and Osaka

N

ow that we had more knowledge of the potential market, it was time to brief the Kinokuniya sales team. With the help of an art history professor, Naoko and I developed a presentation that we took on the road to Kinokuniya’s regional sales force. The professor paid me the rare honour of an invitation to dinner at home with his family. Eager, to ensure that I taste real Japanese food, he offered me natto (sticky fermented soya beans) and a dish aptly named “smelly fish”. Meanwhile, Kinokuniya had assigned to us one of its young managers, Nobuo Utagawa, who came to be a friend who could explain to me, in his faultless English, the mysteries of the Japanese sales system.

Naoko had taught me to introduce myself in Japanese, bow low, and then give my presentation in English. I paused every so often for Naoko to explain “Jacobs-san just said …” I recall vividly entering a sales office in Osaka. At a loud command the entire office rose to its feet and bowed low towards me. Osaka was managed by the redoubtable Mr Fujimoto. Nobuo told me that he was a legend in Kinokuniya for his determined management style. As I addressed Mr Fujimoto’s sales team I had no doubt that they would work tirelessly to sell TDA, or face the wrath of their boss.

Nobuo took me on sales calls so that I could see for myself how the Japanese market worked. On one call at a large campus the sales person was a young woman (a rare thing indeed at that time). We hoped to sell two sets of TDA. I sat patiently while Nobuo and his colleague talked to the librarian, pausing every so often to ask me to answer a question.

At the end of a lengthy meeting the librarian announced that her colleagues had discussed the sale before we arrived. They had agreed that, to be scrupulously fair, the librarians would order one set from Kinokuniya and one from Maruzen. Our smiles hid our disappointment as we thanked the librarian profusely. I learned that the American hard sale had no place in Japan.

-

- The Mysteries of Online Reference

T

DA was the first large-scale academic reference work to be converted to digital form. This was before the advent of Wikipedia and at least a year before the launch of Google’s search engine, so we were true pioneers. At our London launch we demonstrated how a link from the biography of Leonardo could link to the image of the Mona Lisa in Paris. This brought a gasp of surprise from our audience.

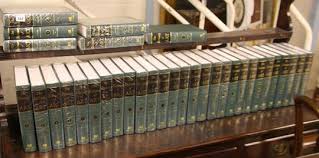

The Dictionary of Art. Photo: Wikipedia

The Dictionary of Art. Photo: WikipediaThe sale on subscription of digital reference required new sales models in all our markets. In Japan we worked again with Nobuo Utagawa and the Kinokuniya sales team. I discovered that librarians had (but only just) become familiar with online journal subscriptions. But they were much more hesitant to subscribe to a reference work. It turned out that a peculiarly Japanese key was required to unlock the market.

Librarians patiently explained to me that they could not subscribe to TDA online because the accountants required them to demonstrate that they had acquired a tangible product. Online data was not tangible. I asked how they were able to subscribe to online journals.

They responded that the journal publisher gave them a CD of the content to show to the accountant, even though the data was not searchable as it was online. Indeed, the CDs were quite useless, except to satisfy the accountant.

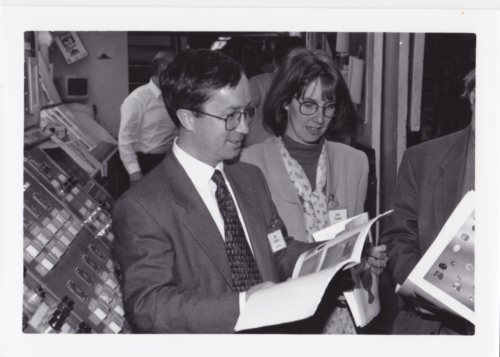

Ian Jacobs and Jane Turner, Editor of The Dictionary of Art, checking page proofs at the printer in Willard, Ohio, 1996. Photo: Ian Jacobs.

Ian Jacobs and Jane Turner, Editor of The Dictionary of Art, checking page proofs at the printer in Willard, Ohio, 1996. Photo: Ian Jacobs.Our decision to go straight to online proved to be more far-sighted than we realized at the time. In the 1990s libraries had two budgets for acquisitions: books and journals.

At first librarians could not work out from which budget to acquire TDA online.

Soon, however, we were negotiating contracts for access by all the libraries in the state of Georgia, US, all university libraries in the UK and all the public libraries in Ireland. We had to invent new models for access and pricing without and guidelines: this was both exciting and quite scary.

Searching was a particular challenge for Japanese customers. I recalled the editor of Kodansha’s Japanese translation of The New Grove telling me that for a year she visited native speakers of various languages asking them to pronounce the names of composers so that she could transcribe them into Japanese characters.

Thus, searching online for names of people, works of art and other proper nouns was particularly difficult for Japanese users. Fortunately, we found a software company that had developed a search engine that could search Roman characters in a database using Japanese characters.

-

- Culture, Language and Sales

I

f we passed a temple or shrine, my colleague Naoko would suggest that we stop and pray briefly. When I asked for what she would reply “For good business. We Japanese are very practical”. I could not imagine a sales colleague in the west taking me into a church to pray for a sale. I had learned my reference sales techniques in the US where I was taught to “sell the sizzle not the steak”, and the art of the close. Japan would have driven my US sales colleagues to distraction. Here painstaking relationship building was the basis of the sale. And the close, at least to this non-Japanese speaker, was so gentle as to be imperceptible.

The Dictionary of Art wrapped for sale.

The Dictionary of Art wrapped for sale.While a US sales person would bank the sale and assume that was the end of the deal, a satisfying sale in Japan was part of a relationship and, at its best, a long friendship. I was fortunate to find some enduring friendships during my adventures in Japan.

-

- Looking Back, Looking Forward

O

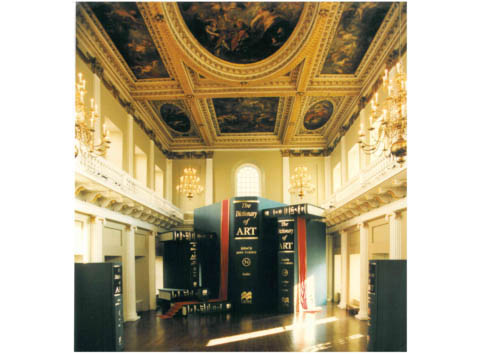

nline publishing puts end users of reference resources directly in contact with the editors and publishers. Feedback combined with the flexibility of digital platforms, enables innovation.  Giant volumes of The Dictionary of Art (TDA) at the launch at the Banqueting House London 1996. Photo: Ian Jacobs

Giant volumes of The Dictionary of Art (TDA) at the launch at the Banqueting House London 1996. Photo: Ian JacobsHowever, we used the index to power a new online feature to power “related article” hyperlinks to additional useful content.

Today, TDA online offers study guides, tours of major art collections and content related to the art market.

There are spinoff print reference works on American Art and Classical Art. Forthcoming projects include a three-volume encyclopedia of Latin American art and architecture and another on Asian art and architecture.

© Ian Jacobs

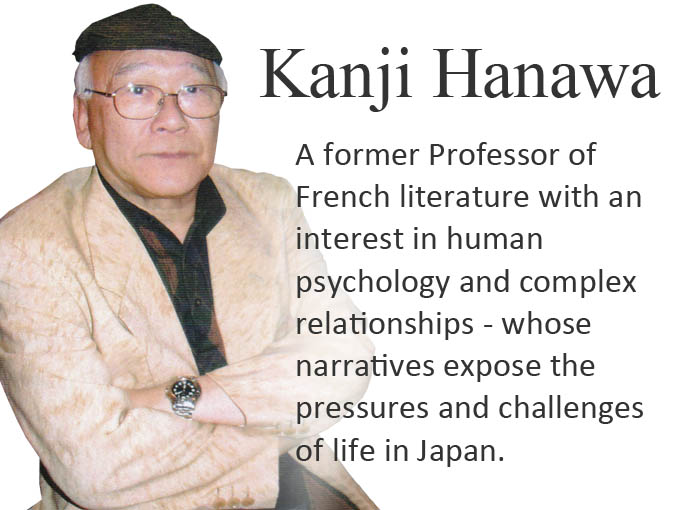

Ian Jacobs: Special Contributor

Ian Jacobs was for 40 years publisher of music and art books with Macmillan and Thames & Hudson. Among other positions he was Vice President of Grove’s Dictionaries of Music, Inc. 1977-1981, Publisher of Macmillan’s Grove Dictionary of Art 1985-1996, Managing Director of Macmillan Reference Ltd. 1997-2001, and Publisher of Thames & Hudson’s higher education division. Tokyo launch at International House, Roppongi. Top right is: Professor Terukazu Akiyama; Naoko Matsumoto; Larissa Haskell; Professor Francis Haskell, Oxford University; Ian Jacobs; Mrs Joan Mondale, wife of Walter Mondale, US amabssador to Japan. Photos: Ian Jacobs

Tokyo launch at International House, Roppongi. Top right is: Professor Terukazu Akiyama; Naoko Matsumoto; Larissa Haskell; Professor Francis Haskell, Oxford University; Ian Jacobs; Mrs Joan Mondale, wife of Walter Mondale, US amabssador to Japan. Photos: Ian Jacobs