Time travel is a popular narrative used in fiction, which J K Rowling, Ray Bradbury, Stephen King, and Mark Twain, just to name a few, have explored and exploited. Authors have been returning to the theme of time since at least the 8th century when the story of Urashima Taro was first recorded. Photograph: Antique watch faces for sale at a Paris flea market. Red Circle Authors Limited.

Time travel is a popular narrative used in fiction, which J K Rowling, Ray Bradbury, Stephen King, and Mark Twain, just to name a few, have explored and exploited. Authors have been returning to the theme of time since at least the 8th century when the story of Urashima Taro was first recorded. Photograph: Antique watch faces for sale at a Paris flea market. Red Circle Authors Limited.T

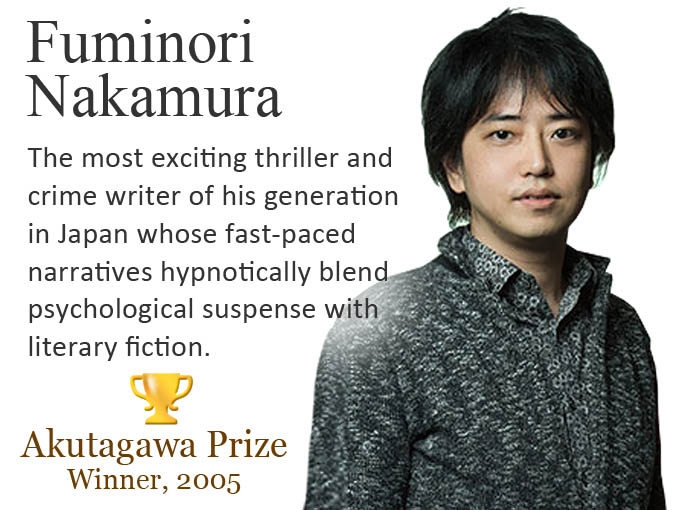

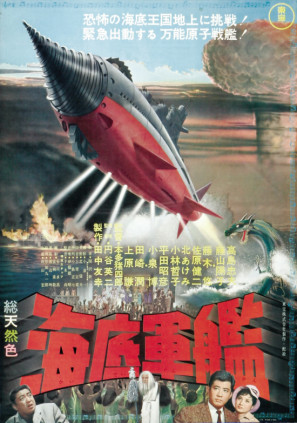

he genesis of today’s science fiction writing in Japan is said to be the translation into Japanese of the French author and playwright Jules Verne’s (1828-1905) novels in the 1880s. The books arrived during a period of rapid modernisation and change in Japan known as the Meiji Era (1868-1912), when Japan was opening up to Western influence after the resignation of the Shogun and more than two hundred years of self-imposed isolation.

Japan was trying to secure its place in an increasingly interconnected world and catch up in an intense technology race. Around the World In Eighty Days and Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea were hugely popular and had a major impact on Japanese authors and readers.

About fifteen years after the arrival of Verne’s novels in Japan, Shunro Oshikawa (1876-1914) published The Undersea Warship: A Fantastic Tale of Island Adventure, in 1900, and modern Japanese science fiction was born.

Book cover of English translation by Shelly Marshall published in 2015.

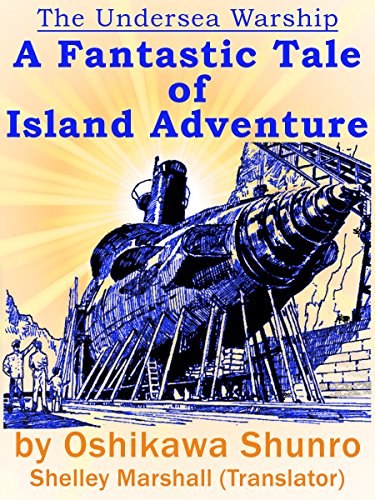

Book cover of English translation by Shelly Marshall published in 2015. Atragon, released in Japan as Kaitei Gunkan, a 1963 science fiction film, based on novels by Oshikawa. Image: Wikipedia.

Atragon, released in Japan as Kaitei Gunkan, a 1963 science fiction film, based on novels by Oshikawa. Image: Wikipedia.Captain Sakuragi replaces Captain Nemo in what was an extremely popular six-book series that mirrored the times and predicted the future.

The captain and his crew confront Japan’s rivals and enemies in imagined submarine warfare of the future in advance of the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War of 1904.

The reality, however, like many things in Japan, is much more complex. In fact, science fiction is believed to have even earlier roots within Japanese folktales and Chronicles of the Future, Mirai-ki, a genre of storytelling that imagined the future and helped contextualise and prepare people for change.

T

he first Mirai-ki are said to have been created by Shotoku Taishi (574-622) – The Prince of Holy Virtue – a regent and author also known as Prince Umayado (Prince of the Stables) as he was born unexpectedly – some say somewhat miraculously- at a stables. He is an important historical figure in Japan and still admired today. His image was included on 10,000 yen notes issued until 1986, and he is credited with developing Japan’s first set of laws – a set of 17 rules – which stress the importance of harmony in the community. The rules have been described as an early type of constitution. According to legend the somewhat mythical Shotoku, who was the first champion of Buddhism in Japan, is reputed to have been able to listen to 10 people talking simultaneously and predict the future.

His Mirai-ki are recorded in Japan’s second oldest history book, Nihon Shoki. Copies are said to be stored somewhere within Shitenno-Ji, one of the country’s oldest Buddhist temples. The temple was commissioned in 593, by Shotoku himself, in what is now Osaka.

Mirai-Ki are generally set in the future but are about past events allowing readers to rethink their current time, their position in it, and how they might instigate a new path into the future.Mirai-ki are generally set in the future but are about past events allowing readers to rethink their current time, their position in it, and how they might instigate a new path into the future.

It was possibly a form of ancient storytelling to assist ‘change management.’ Implementing change and modernising Japan are achievements Shotoku is still praised for today.

It may seem far-fetched, but a modern equivalent might in fact be the motivational fable Who Moved My Cheese? published in 1998 just as concern around the so-called millennium Y2K bug was growing and many were worried about losing their jobs through reorganisations: not traditional science fiction: but possibly functionally similar.

These types of Japanese stories, which didn’t generally speculate about the future, as is usually the norm in much contemporary science fiction, continued to be written; establishing the genre of Mirai-ki, records or chronicles of the future.

They were published during the Edo Period (1603-1868) mostly as satire; and subsequently there appeared a flurry of Mirai-ki novels influenced by new types of books from Holland and other countries.

2065: A Glimpse of the Future by the Dutch biologist Pieter Harting (1812-1885), for instance, and other such titles became available in translation in Japan in the late 19th century, depicting both utopian and dystopian worlds just as the new millennium approached and Japan was experiencing a period of rapid unsettling political and technological change.

It has taken a long time, and special initiatives such as books like Monkey Brain Sushi: New Tastes in Japanese Fiction, a collection of short-form fiction, to help increase interest in Japanese science fiction in translation. This particular anthology includes: Girl, a short story by the science fiction writer Mariko Ohara, Mazelife by Koji Kobayashi, Momotaro in a Capsule by Masahiko Shimada as well as works and extracts from works by Haruki Murakami and others. Another example is the now rather dated collection The Best Japanese Science Fiction Stories (1989). Lists of so-called speculative fiction in translation including science fiction have also played a role. Photograph: Statue for sale in a novelty furniture store in central Paris. Red Circle Authors Limited.

It has taken a long time, and special initiatives such as books like Monkey Brain Sushi: New Tastes in Japanese Fiction, a collection of short-form fiction, to help increase interest in Japanese science fiction in translation. This particular anthology includes: Girl, a short story by the science fiction writer Mariko Ohara, Mazelife by Koji Kobayashi, Momotaro in a Capsule by Masahiko Shimada as well as works and extracts from works by Haruki Murakami and others. Another example is the now rather dated collection The Best Japanese Science Fiction Stories (1989). Lists of so-called speculative fiction in translation including science fiction have also played a role. Photograph: Statue for sale in a novelty furniture store in central Paris. Red Circle Authors Limited.D

during the next century, Japanese writers like Kobo Abe (often described as Japan’s Kafka), whose 1956 title Inter Ice Age 4 is sometimes credited as Japan’s first full-length science fiction novel, and other brilliantly creative writers including Shinichi Hoshi (best known for his short stories like Miss Bokko about a young female robot); as well as Sakyo Komatsu, Yasutaka Tsutsui and Masaki Yamada continued, developed and expanded the tradition.The science fiction genre in Japan is now established and supported by numerous prizes and competitions including: the Nihon SF Taisho Award; the Hoshi Prize, named after the author; and the Seiun Award for the best science fiction, awarded by the Federation of Science Fiction Fan Groups of Japan (FSFFGJ). This prize was first awarded in 1970 to Yasutaka Tsutsui author of The Girl Who Leapt Through Time, a story about a time traveling girl published in 1967 that has been adapted for television and film several times and released as an animated film in 2006.

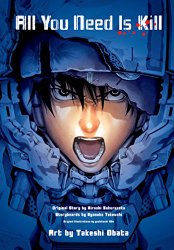

Cover of All You Need Is Kill by Hiroshi Sakurazaka, the highest ranked Japanese novel on the 2014 list of Best Non-English language Science Fiction Books.

Cover of All You Need Is Kill by Hiroshi Sakurazaka, the highest ranked Japanese novel on the 2014 list of Best Non-English language Science Fiction Books.Books often praised and mentioned include: All You Need is Kill, by Hiroshi Sakurazaka, which has been made into a Hollywood film titled Edge of Tomorrow starring Tom Cruise; Battle Royale by Koushun Takami, Japan Sinks by Sakyo Komatsu, Paprika by Yasutaka Tsutsui, Ten Billion Days and One Billion Nights by Ryu Mitsuse, and Gene Mapper by Taiyo Fuji.

As well as novels and short form fiction, Japan’s creatives such as Osamu Tezuka (1928-1989), sometimes called the Walt Disney of Japan, (Astro Boy, Testuwan Atomu & Phoenix, Hi-no-Tori) have produced numerous science fiction manga and anime. Highly regarded examples include: Akira (Katsuhiro Otomo) and Ghost in the Shell (Shiro Masamune).

H

G Wells’ (1866-1946) novel, The Time Machine (1895), is often credited with introducing the concept of time travel to the masses and science fiction writers. But stories of time travel in Japanese folk stories predate Wells and countless others like J K Rowling, Lewis Carroll, and Charles Dickens, who have all used the narrative device of time travel in their novels. Japanese tales of old, Mukashibanashi, contain beautifully captivating tales of time travel, shape-shifting and even extra-terrestrial visitations.

Urashima Taro, one such tale, is a sad story that involves time travel, a visit to a Dragon Kingdom at the bottom of the ocean where a beautiful princess lives, and a magic box that wards off the passage of time if left unopened.

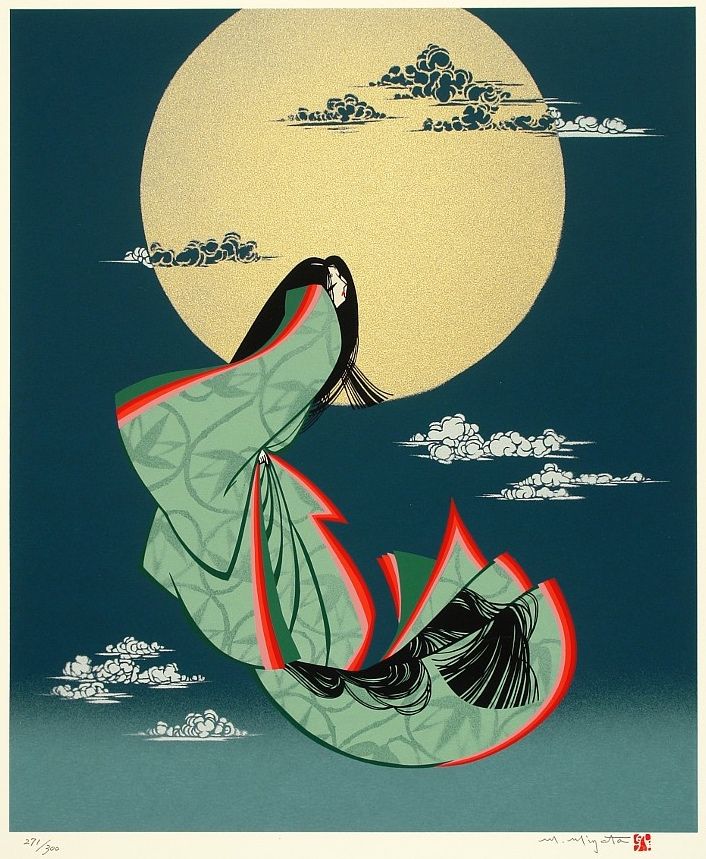

Woodblock print by Masayuki Miyata (1926 -1997) of Princess Kaguya soaring to the Moon from a modern illustrated edition of The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter. Miyata is best known for his Kiri-e work (paper cutting). He was apparently ‘discovered’ by Junichiro Tanizaki author of The Makioka Sisters (1943-48) who was shortlisted for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1964.

Woodblock print by Masayuki Miyata (1926 -1997) of Princess Kaguya soaring to the Moon from a modern illustrated edition of The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter. Miyata is best known for his Kiri-e work (paper cutting). He was apparently ‘discovered’ by Junichiro Tanizaki author of The Makioka Sisters (1943-48) who was shortlisted for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1964.The story of Princess Kaguya, also known as The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter, ends with the Princess returning to her true home, the Moon, after an entourage from the Heavens collect her from Earth in a spacecraft, leaving her grieving adopted family behind.

The film magazine, Empire, called Elliott and E.T.’s flight to the forest: “the most magical moment in cinema history”. Image: Wikipedia.

The film magazine, Empire, called Elliott and E.T.’s flight to the forest: “the most magical moment in cinema history”. Image: Wikipedia.Some people go as far as arguing that the film is in fact an homage to this old Japanese tale of a visiting alien child.

The story has inspired and entertained many, even Japan’s astrophysicists and satellite engineers. The Japanese VLBI spacecraft, The Kaguya Lunar Obiter, named after the Princess circumnavigated the Moon between 2007-2009, taking photos of it in Ultra-High Definition. These included a breathtaking series of images and footage widely reported by the world’s media as the Earth ‘Rising’ from the Moon.

Science fiction is defined as “fiction dealing principally with the impact of actual or imagined science on society or individuals or having a scientific factor as an essential orienting component”. Japan’s wonderfully rich legacy, the growing international interest in its culture, as well as the technological developments that have allowed ‘Princess Kaguya’ to capture images of our planet from the Moon will no doubt inspire the next generation of Japanese science fiction writers to think big and globally, whether they exploit the techniques and narratives of Mirai-ki, modern science fiction, or imagine and invent brand new ones.

© Red Circle Authors Limited

The super moon rising above a bridge. Photo: halfrain (Wikimedia)

The super moon rising above a bridge. Photo: halfrain (Wikimedia)