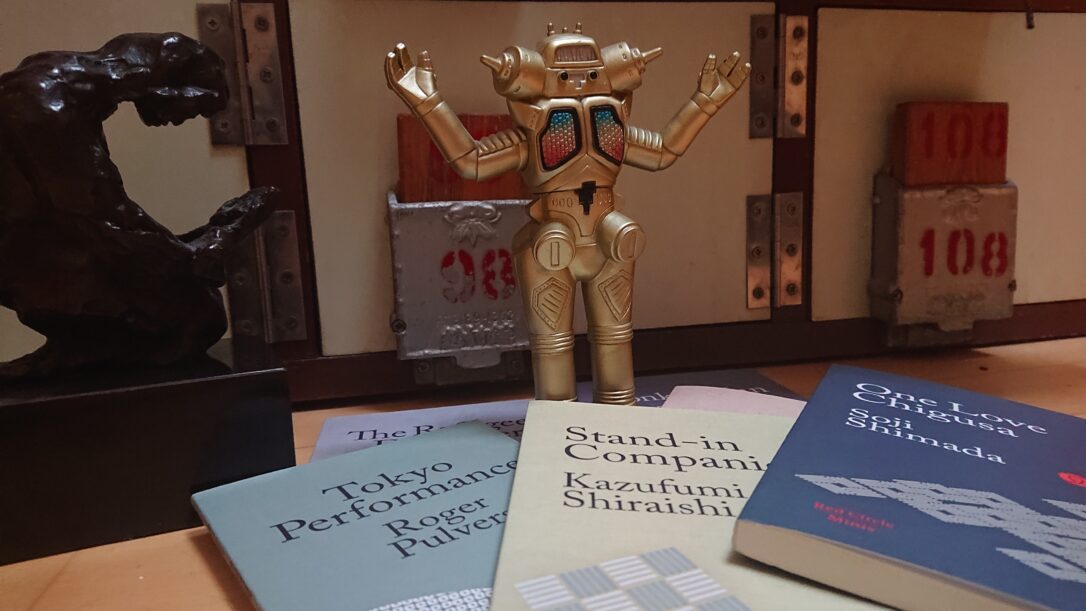

Girl by Tsune Nakamura (1887-1924), Nakamuraya Salon Museum of Art. Imagine: Wikipedia

Girl by Tsune Nakamura (1887-1924), Nakamuraya Salon Museum of Art. Imagine: WikipediaA

picture or indeed a single look is said to be worth a thousand words and a good work of art or a sketch, according to Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821), better than a long speech.To bring some portraits or works of art to life for modern audiences, however, a history needs to be conjured up, imagined or dramatised and the answer to the question, Who was the girl?, for instance, artificially manufactured.

This sometimes requires a book or a work of fiction. But there are some individuals captured in oil, whose narratives are so vivid and extraordinary that they only need to be heard.

One such person is Toshiko Soma (1898-1925) captured in 1914 age 15 in Girl, Shojo, the last of several portraits of her by the Japanese artist, Tsune Nakamura (1887-1924).

It was painted the year when Japan declared war on Germany, on 23 August, as part of the subsequently victorious Allied Powers of World War I.

An act that led to Japan taking over German-leased territories in China and German controlled islands in the North Pacific Ocean such as the Marshall Islands, which are now an associated state of the United States and the infamous location of some 67 nuclear tests, including the largest atmospheric nuclear test conducted by the United States in 1954.

That said, long before the spectre of nuclear war, in this final portrait, an intelligent healthy looking girl, mature for her age, is depicted gazing out in the direction of the artist, not directly at the viewer, with a quizzical expression. We get a sense that she may be challenging the artist as to the purpose of this sitting, and wondering how their futures might unfold once the painting was complete.

Her oversized forearms and long fingers resting on a closed yellow-covered book highlight her education and openness to ideas, but perhaps also indicating a chapter in her life is about to end or start.

Nakamura, the artist from the Yoga school of westernised artists, as opposed to practitioners of traditional Japanese art, was an associate of Rokuzan Ogiwara (1879-1910) a recognised Japanese sculptor of some repute who studied painting and sculpture in New York and in Paris with Auguste Rodin (1840-1917).

International study partly paid for by the patrons that these two Japanese artists shared: Toshiko’s parents.

Nakamura hadn’t actually wanted to be an artist. He would have preferred a career in the military, but contracting tuberculosis when he was 17 closed off that route for him.

Tuberculosis was considered a romantic and artistic condition in Japan at that time and during his initial recuperation Nakamura decided that he wanted to become an artist, which eventually led to him in 1911 living and working at Toshiko’s parents’ studio in Tokyo.

Shortly after which he started coughing up blood as his condition worsened. Despite this, Toshiko became his preferred model and muse. The sculptor Ogiwara had left the Shinjuku studio by then and had tragically died.

Nakamura painted several portraits of Toshiko including images of her reading and also scandalously half-naked.

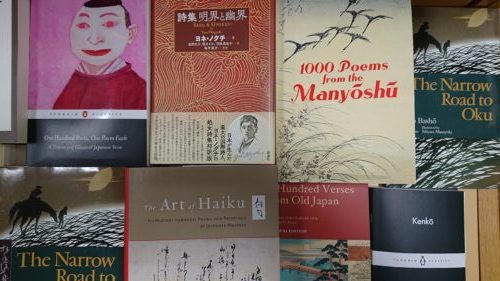

Girl Nude, 1914, by Tsune Nakamura (1887-1924) Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art Imagine: Wikipedia

Girl Nude, 1914, by Tsune Nakamura (1887-1924) Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art Imagine: WikipediaThis portrait, which shows a shy-looking Toshiko with Renoir-like flushed cheeks sitting on a western-style sofa naked with a yellow cloth on her lap looking gently at the artist, was displayed publicly at an exhibition in Tokyo.

The two, the artist and his young muse, living in close proximity were apparently falling in love.

Nevertheless, Toshiko’s parents perhaps unsurprisingly received a complaint from her school after the picture’s public display questioning their approach to parenting, as well as their good Christian values.

Subsequently, in August 1915 Nakamura did the right thing and asked Toshiko’s parents for their daughter’s hand in marriage; a proposal that was turndown by Toshiko’s mother, Kokko, leading to Nakamura drifting away from the Somas circle, and subsequently setting up his own studio in Tokyo, also in Shinjuku.

He died almost a decade later, aged 37, on Christmas Eve 1924.

It is unclear if his proposal was public knowledge, but the teenage Toshiko’s future marriage prospects and reputation would not have been enhanced by the half-naked portrait and this particularly exuberant episode.

-

- Tastemaker Parents

T

he Somas, Aizo and Kokko, weren’t your typical early twentieth century Japanese parents. They were both Christians and met because of their faith.Kokko was a pen name taken on at school, coined by a teacher, due to Toshiko’s mother’s early literary ambitions. The name had an embedded message of caution, as it was written using two seemingly contradictory kanji characters, letters, dim and shinning.

Only moderate success and prominence would be considered acceptable for most women with cultural ambitions in Japanese society during its Meiji period (1868-1912) when the nation was frantically modernising and trying to catch up with the West after more than two hundred years of self-imposed isolation. Therefore to asssure success a strategy of not allowing ones natural talent and ambition to shine too brightly was optimum.

Her wealthy husband, Aizo, didn’t share those views. He believed not only in romantic love, but partnerships based on equality, as well as temperance. He encouraged his wife to embrace modernity and they worked together in myriad ways while also having 9 children, including their oldest Toshiko.

Neither of them were born in Tokyo, but in 1901, three years after they married and a few years after the birth of their first child Toshiko, they bought a bakery in the Japanese capital outside Tokyo University, Nakamuraya. (There is no connection to the artist Nakamura.)

This kicked off their careers as entrepreneurial trendsetting bakers – a dynamic and radical couple active within Tokyo’s expanding cultural scene.

In 1909 they moved their growing business to Shinjuku, an up-and-coming part of Tokyo where a station had been opened in 1885. The station developed rapidly as more and more lines were added, and it eventually became what is now described as ‘the world’s busiest station’, by the Guinness Book of Records.

-

- Baking Faith: Righteousness and Hope

C

hanging one’s location, doing a geographical as some like to call it, within a city or moving to a new country or town to reinvent oneself or one’s career or simply to escape an awkward past, is something many have tried and still do today: sometimes with remarkable results especially if the timing is right.The decision by Aizo and Kokko to make this move away from their surroundings of the nation’s most important seat of higher learning was made just before Japan entered a new democratising and more prosperous and open period, the Taisho era (1912-1926). The name of which when translated directly into English means the era of great righteousness. Though a frenetic era of upheaval, it was a period of hope.

Aizo and Kokko were aged 31 and 25 respectively when they started their careers in the baking and confectionary business and despite her young age, Kokko was already showing a real flare for: spotting new trends; canny promotion; and opportunistic cultural networking.

She and her husband built a studio behind their shop in Shinjuku for Ogiwara (the family friend and sculptor who had studied under Rodin in Paris with their financial support) for him to use on his return to Japan.

Ogiwara lived at the studio in close proximity with the Soma family. This positioned them at the intersection of business, art and culture in this expanding and soon to become vibrant part of Tokyo; a location with a very different profile to the area enclosing Tokyo University.

Their circle included activists, poets and university professors as well as artists – locals, returnees and non-Japanese alike – generating a creative milieu that led to the creation of new products and business ideas.

This included their kurimu-pan, a type of cream bun still popular today, which they invented and launched in 1904, as well as new ways of packaging and selling snacks, such as the crispy bite-sized snack karinto, and much more besides.

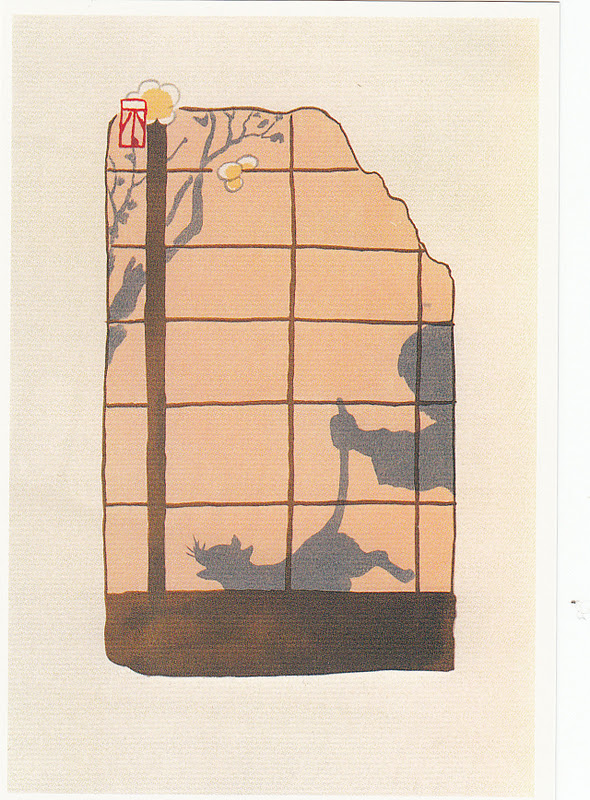

Illustration by Fusetsu Nakamura (1866-1943) from I am a Cat by Natsume Soseki (1867-1916) .

Illustration by Fusetsu Nakamura (1866-1943) from I am a Cat by Natsume Soseki (1867-1916) .He had also studied in Paris and had some of his work exhibited there at the 1900 Exposition Universelle where he even won a minor prize. He is also remembered for his delightful illustrations of Natsume Soseki’s (1867-1916) breakthrough work, I am a Cat.

The Somas also became involved in the Pan-Asian Movement, which might today be called the Indo-Pacific Alliance. They were also part of the compact network of so-called Japanese Christian intelligentsia.

The business flourished and they added a café and restaurant and the studio expanded from an atelier into a cultural salon attracting Japan’s literati, as well as intellectuals and artists including Nakamura, their daughter’s portrait painter.

-

- Bread of Affliction: Buns and Longing

I

t wasn’t just their daughter, Toshiko, who inspired an artist. Kokko also had a magical effect on others, especially on Ogiwara, who is sometimes referred to today in Japan as The Rodin of the East.Ogiwara, reportedly fell in love with a Soma woman just like another artist was destined to do a few years later. Ogiwara, also a Christian, struggled with his conflicted feeling for his patron, Kokko, who personified beauty, unrequited love, and Ogiwara is often quoted as having said: “Love is art, struggle is beauty.”

Ogiwara’s final work Woman, which he completed in the Nakamuraya studio, is considered an important Japanese masterpiece. It was the first modern sculpture to be designated an Important Cultural Property by the Japanese government.

Twenty days after completing his final masterpiece, Woman, in 1910, Ogiwara abruptly left the Nakamuraya studio and tragically died shortly afterwards that year, in April, at the age of 30.

A 2007 television drama, Rokuzan’s Love, tells his story focusing on his ‘forbidden love’ for Kokko, the artist’s muse and, according to the television drama, the model for Woman. The actual model, however, for what is probably his most sensual work, was officially a different unnamed woman.

This wasn’t, however, the first or only television drama to feature Nakamuraya and their tale. The first such drama was Buns and Longing, broadcast nationally in Japan also by TBS in 1969.

Woman by Rokuzan Ogiwara (1879-1910): Image: Wikipedia

Woman by Rokuzan Ogiwara (1879-1910): Image: WikipediaOgiwara’s official cause of death was tuberculosis but some speculate that he actually killed himself, using poison, having perfected his greatest work depicting the perfect woman, the woman he loved, Kokko, Toshiko’s mother.

Whatever the truth behind the rumours surrounding both Kokko and Toshiko and their relationships with these troubled pioneering artistic Japanese men, who both lived embedded lives amongst the Soma family, neither of these two dynamic Soma women – mother nor daughter – developed a long-term sustainable partnership with a Japanese artist, even if they are both now imprinted on modern Japanese art and its somewhat bohemian narrative history.

There was also much more to each of these unusual women and their lives than that of artists’ muses and objects of desire.

-

- Changing Places: Tomorrow’s Women

T

oshiko and her mother, Kokko, were living in an exciting period in Japanese history, especially for young residents in and around Tokyo. The nation was urbanising and changing fast.World War I had created a mini-economic boom for Japan and Tokyo was becoming an exciting metropolis with a population of more than 2 million with more money to spend.

Japan attended the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, as a military and newly industrialised power and one of the five major nations taking charge of a new world order.

Before the exuberant Taisho period of 1912, Japan had already opened up to the West and adopted many West ways, through fashion, cuisine and changed its outlook and view of the nation’s place in the wider world.

Modern Girls (modan garu) wearing “Beach Pajama Style” with modern bob-cut hair styles walking down Ginza, Tokyo, in 1928. Photograph: Wikipedia.

Modern Girls (modan garu) wearing “Beach Pajama Style” with modern bob-cut hair styles walking down Ginza, Tokyo, in 1928. Photograph: Wikipedia.Things were very different in the decades that proceeded. In 1890, for example, only 31% of girls completed primary level education. This subsequently rose to 72% in 1900, and a decade or so later in Taisho Japan, women had started entering the workforce as waitresses, nurses, bus conductors, and typists, often wearing western-styled uniforms. This helped spawn new fashions, and individuals known as mobo and moga, modern-boys and modern-girls made their first appearance.

Even Freudian psychoanalysis had arrived in Japan in translation, as had Lewis Carroll’s (1832-1898) Alice in Wonderland, Author Conan Doyle’s (1859-1930) Sherlock Holmes, and Charles Darwin’s (1809-1882) On the Origin of Species.

Western cookbooks and style guides were being published in Japanese for Japan’s increasingly newly literate population who had an insatiable appetite for reading and all things western.

Trendy European style cafes were opening up catering for this new generation who felt and acted very differently from their parents and grandparents. Entrepreneurs began launching new business ventures often targeting this new class of urban-dwelling consumers.

Edo Japan (1603-1867), when the nation was cut off from the world and ruled by Shoguns, was now a distant memory; an alien world. This new generation, with its open and experimental attitudes, and the New Japan, would have seemed as perplexing and incomprehensible to earlier generations, as early Edo would now have seemed to Taisho youth.

Freshly baked bread on sale in Tokyo. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited

Freshly baked bread on sale in Tokyo. Photograph: Red Circle Authors LimitedAttitudes towards sexuality became less victorian and were again much more open. They could even at times be fluid and new style romance writers like Nobuko Yoshiya (1896-1973) with her independent and adventurous spirit started romancing Japan’s reading public helping create a new genre of increasingly popular and commerically successful books, the modern romance.

Yoshiya lived openly as a lesbian and in 1919 wrote a novel, titled Two Virgins in the Attic. She was so prolific and successful that she earned enough royalties to support her chosen lifestyle, which included being the first woman in Japan to own a car and adopt her partner in an early form of same-sex-marriage.

-

- Tokyo Calling

W

hen economic prosperity, increasing openness and political and emerging societal freedom converge, a city can feel as if it is the epicentre of the world. Taisho Tokyo was just that for some, a hugely exciting and enjoyable time full of strangeness and opportunity up until the 1923 devastating Great Kanto Earthquake, which tragically destroyed much of Tokyo and changed the nation’s trajectory. Image of Tokyo after the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake. Image: Public Domain.

Image of Tokyo after the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake. Image: Public Domain.Bowie was great fan of Japan with his own private residence in Kyoto purchased from the proceeds of promoting drinks for the Kyoto-based Japanese food and drinks company Takara Shuzo.

He spoke publicly about his love of Japan and considered moving here permanently in the 1980s. He was fascinated by Japanese authors like Yukio Mishima (1925-1970), as well as designers and musicians. Sakamoto, the composer, singer and songwriter had a major influence on his work.

By the dawn of the twentieth century, the West had become increasingly aware of Japan and its attractions. The Nobel Prize committee recognised the insights of Rudyard Kipling’s (1865-1936) writing on the manners and customs of the Japanese when they awarded him his Nobel Prize in 1907. The year the Somas started planning their move to Shinjuku.

Kipling made two well-documented trips to Japan – the first when Kipling was still an unknown India born man traveling through Japan on route to the United States in his 20s.

In fact, by the early 1900s so many books had been published ‘Explaining Japan’ that some authors even felt compelled to write books that both summarised and refuted them.

Japan or at least Tokyo was becoming the land of the rising hipster, and started to attract the attention of adventurous individuals from outside Japan, in the same way as it would in the 1980s.

-

- Taisho Era Talent Management

O

ne such man was a blind violin-playing Esperanto-speaking Russian poet called Vasili Eroshenko (1890-1952). He moved to Japan in 1914 to study massage at the school for the blind in Tokyo. The year Toshiko’s final portrait by Nakamura was painted.Learning Esperanto, the first so-called International Language invented in 1887, was de rigueur in Japan at the time and some trendy Japanese clubs and associations encouraged their members to speak this artificially created easy to learn universal language, the name of which means: one who hopes.

Eroshenko stayed for about two years, learning to speak Japanese and even started publishing children’s books in Japanese, before returning again in 1919 through Shanghai from India. He became a major celebrity traveling across Japan drawing large crowds.

Being blind and blonde made him an object of fascination. The fact that he was blind and could therefore not judge the Japanese by their skin colour, added to his charismatic allure.

He gave talks alongside Japanese authors including Mimei Ogawa (1882-1961), famed for his short stories, fairy tales and children’s books. Many writers became regular visitors to the Nakamuraya cultural salon.

The salon rapidly became a nighttime campus for Tokyo radicals, intellectuals and artists, as well as a place to learn about art, and study the Russian language as well as discuss exciting new forms of literature. All of which fascinated Kokko. In 1913 she started taking Russian lessons from a professor at Waseda University.

Eroshenko was probably one of the best known foreigners living in Japan at that time. He would be known today in Japan as a Gaitare, a foreign celebrity or media personality.

He, like many other talented Taisho individuals, fell into Kokko’s orbit and ended up living with the Somas in Shinjuku – something that the Somas weren’t afraid to make widely known.

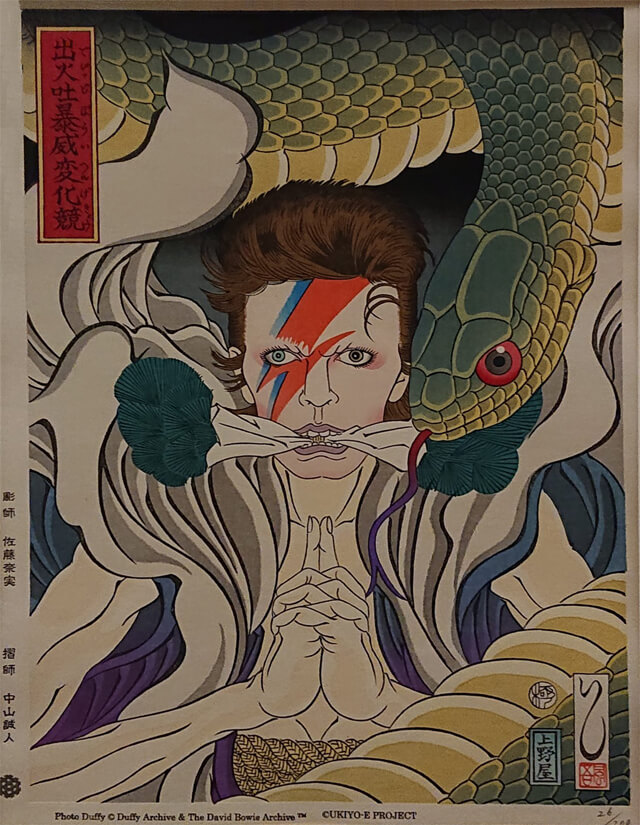

David Bowie Shapeshifting Comparison 2017-18 by Ishikawa Masumi. Bowie as Aladdin Sane morphs in this image, at the British Museum in London, into Kidomaru a Japanese warrior-magician. Photo: Red Circle Authors Limited

David Bowie Shapeshifting Comparison 2017-18 by Ishikawa Masumi. Bowie as Aladdin Sane morphs in this image, at the British Museum in London, into Kidomaru a Japanese warrior-magician. Photo: Red Circle Authors LimitedNakamura, their daughter’s portrait painter, painted a famous portrait of Eroshenko wearing a rubashka, a type of tunic worn by Russian peasants, which they proudly exhibited. In many ways, Eroshenko became an early Bowie-like figure in the way he assumed the role of brand ambassador and product promoter for the Somas and Nakamuraya.

Portrait of Vasili Eroshenko (1890-1952) by Tsune Nakamura (1866-1943)

Portrait of Vasili Eroshenko (1890-1952) by Tsune Nakamura (1866-1943)The Japanese authorities reportedly considered him a potential Bolshevik and, despite or perhaps because he was a poet and free spirit, the most dangerous foreigner living in Japan.

He was abruptly deported in 1921, a controversial decision that made headline news. The same fate, of course, would not befall Bowie, that other famous experimentalist and rebel.

In a savvy business response to Eroshenko’s deportation, Kokko managed to keep his visibility, and what might today be called brand equity, alive by adopting Russian style uniforms for their employees the year of his deportation in honour and memory of him.

She also hired a Russian baker, launched a range of Russian-type bread, and cleverly added a “Russian” soup, borscht, to their restaurant’s menu; a sensible selection in a soup-loving nation like Japan where most meals are served with soup.

-

- Rising Prose

I

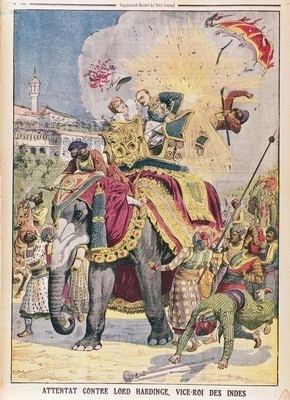

n addition to artisan bakers and trendsetting cafes, Taisho Japan also had its own trendsetting, ‘it’, magazine for the young literary in-crowd, White Birch, Shirakaba (1910-1923), a monthly publication. There was increasing interest in Russian and international literature, a trend that Nakamuraya and its owners embraced and stoked brilliantly. Assassination attempt on Lord Charles Hardinge (1858-1944) Viceroy of India, illustration from Le Petit Journal, 12th January 1913 (colour litho) by French School, (20th century); Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris, France. Source: Wikipedia

Assassination attempt on Lord Charles Hardinge (1858-1944) Viceroy of India, illustration from Le Petit Journal, 12th January 1913 (colour litho) by French School, (20th century); Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris, France. Source: WikipediaNaturally, it delighted the Japanese literati, and inspired many Japanese authors writing in the Japanese language into thinking that international success was a possibility. Yasunari Kawabata (1899-1972) Japan’s first nobel literature laureate who won the prize in 1968 would have been a teenager at the time.

In 1915, two years after Tagore won his Nobel prize another Bengali used Tagore’s literary success to escape India and gain safe passage to Japan, later joining Eroshenko at Nakamuraya. A decision that changed the Somas and Toshiko’s lives dramatically.

His name was Rash Bihari Bose (1886-1945). He was a young man aged 29 with a past, and was on the run, having tried unsuccessfully to assassinate Lord Hardinge (1858-1944) the Viceroy and Governor General of India in Delhi on 23 December 1912.

Hardinge who was with his wife riding an elephant at the time was wounded in the shoulder. His wife was unharmed. The incident, an act of insurgence designed to spark a revolution, even led to questioning of the Under-Secretary of State for India in the Houses of Commons in London about the conspiracy and the arrest of the perpetrators.

Bose used an alias, Priyanath Tagore, pretending to be a relative of the Nobel laureate, to escape to Japan.

-

- From Glamour Model to Sari-Wearing Mother

I

nitially on Bose’s arrival, various Pan Asian groups in Japan underground networks of radicals, activists, progressives and revolutionaries who wanted Asians to unite against European imperialism, develop an Asian voice and system of values – some as a form of liberalism and others as nationalists – hid and looked after Bose.His first visit to the Somas at Nakamuraya was in the spring of 1916, the year after Nakamura the artist had moved out. And it was here that he would occasionally stay overnight in hiding.

In their attempt to track him down and have him deported back to India, the British authorities hired private detectives. But like others, Bose eventually ended up living at the cultural salon on the second floor of Nakamuraya in Shinjuku.

Interestingly, in 1916, the Indian Nobel laureate who had indirectly helped Bose escape to Japan did actually visit the country, and the Somas would undoubtedly have been involved with his visit and associated events.

The trip, which lasted several months, caused considerable excitement drawing crowds and was covered in Japanese newspaper such as the Asahi Shimbun. This was partly due to three short poems Tagore had written on Japan’s victory over Russia in 1905.

Tagore gave several notable speeches, including one on India and Japan, arguing against jingoistic nationalism, even though he was a staunch patriot and believed in the value of the East and independence.

In an eloquent speech just before leaving Japan on the first of his five visits, titled: The Spirit of Japan, he warned the nation against “imitation of the outward aspects of the West” and about “the hounding wolves of the modern ear”.

Despite this, the place of nature in Japanese literature and culture and the so-called Japanese aesthetic is said to have had a deep impact on him, as did he on many in Japan. He described this temperament towards nature as “the genius of Japan”. But during later visits after the Taisho era had ended, Japan’s increasing militarism and jingoism, which seemed to be replacing dynamism and openness, is said to have troubled him.

Even after Bose’s deportation order was finally rescinded, following several months in the Nakamuraya cultural salon’s guesthouse, Bose’s status in Japan remained extremely precarious. And that is when a solution was proposed by a leader and controversial figure in the Pan-Asian Movement, Mitsuru Toyama (1855-1944), a shadowy and elusive figure sometimes referred to as the Shadow Shogun who was also the founder of the Black Dragon Society, a paramilitary group. He proposed that the Soma’s eldest daughter, Toshiko, should marry Bose, as both were still unmarried, and a marriage would allow Bose to apply for Japanese citizenship.

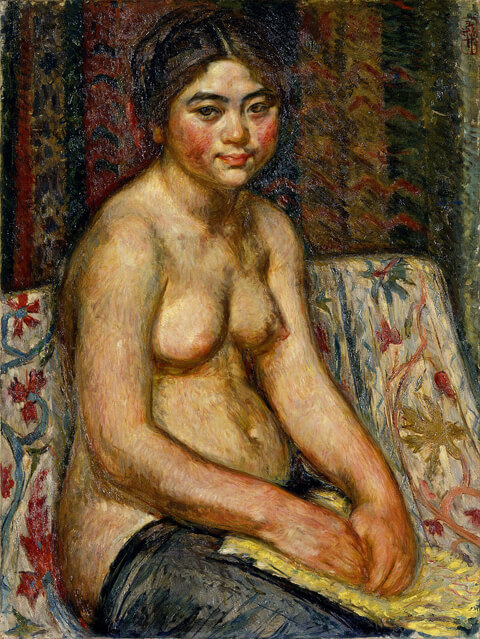

Toshiko and Kokko Soma wearing Saris. Image: Bose of Japan.

Toshiko and Kokko Soma wearing Saris. Image: Bose of Japan.They were already familiar as Toshiko had been helping look after Bose and translate for him, but she was only 19, and despite the heady times, international marriages were still very rare in Japan.

It took several weeks for Toshiko to make her mind up, but she eventually decided to go ahead with the proposed plan and they were married in July 1918 in a secret private ceremony.

This was a memorable and historic year on many fronts. It was the year of the Spanish Flu, which killed millions, including for example Gustav Klimt (1862-1918), and many in Japan. It was also the year that the Bolsheviks killed the Romanovs, the Russian Imperial Family, while Moscow became the capital of the Soviet Union.

About a year later Toshiko gave birth to a son and a daughter followed shortly afterwards. But life was a constant worry and they moved multiple times, wary of surveillance, kidnap or assassination.

Toshiko learnt some Bengali and even occasionally wore a sari. Her new life on the run with a fugitive that the British considered a terrorist would have been totally unimaginable when she had originally sat for those portraits in her early teens for the artist Nakamura, who had asked her parents for her hand in marriage.

-

- How Strong is the Shield?

B

y all accounts Toshiko was dedicated and devoted to her husband. The couple bonded and apparently fell in love. Toshiko had morphed in the space of just a few years from a career-defining artist’s muse, to the life-saving wife of an Indian anti-colonialist revolutionary and a mother of two.In July 1923, a few months before much of Tokyo was destroyed by the Great Kanto Earthquake that killed more than a hundred thousand people, Bose was naturalized becoming a Japanese citizen, finally allowing the couple to move into their own home in Sendagaya.

Sadly, their home was destroyed shortly afterwards in the earthquake of 1 September and, like for many others, a secure and simple family life would continue to elude Toshiko and her family.

Tragically, despite her husband’s newly found security in Japan, Toshiko’s health began to fail. Less than two years later, in March 1925, the year of Mishima’s birth, she died from a respiratory illness, probably tuberculosis.

Her death was one year after the death of Nakamura, her portrait painter, and tragically a few years after the first use in humans of the anti-tuberculosis BCG vaccine in 1921. It was a period when the spectre of death hung over Tokyo. Despite watching over her husband, keeping him from danger, fate caught up with them.

Toshiko was only 26 years old, but in her short intense life, and especially the period since her semi-naked portrait was exhibited, her life had been a feverish whirlwind of events reflecting both the opportunities and extremes of Taisho Japan. A period that came to an end one year later in 1926 with the death of Emperor Yoshihito when the Showa Emperor took over from his father and the Showa era began (1926-1989).

Sometimes individual acts can change nations and history. Toshiko’s husband had tried to instigate such a change in India before his arrival in Japan. But unpredictable seismic events like pandemics or the huge 1923 earthquake, can trigger dramatic change too. Such events stop nations or individuals from exploiting golden new opportunities, and alter the natural course of things. In this regards, Japan and its Taisho era are no exception.

Bose continued to fight for Indian independence campaigning, writing, lobbying and organising and even launched a bi-lingual English-Japanese journal titled The New Asia.

He chaired the Indian Independence Conference in Bangkok in 1942, which helped found the Indian National Army (INA) and the Free India movement.

The task of bringing up his children was left to Toshiko’s parents after her death. Despite this, Bose never remarried nor wished to and he was buried together with Toshiko after his own death, also from a respiratory illness, in 1945. Sadly, before India gained its independence in 1947, leaving a potential symbolic intersection with a historic milestone unfulfilled.

Rash Bihari Bose (1886-1945) with Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) his two children and parents-in-law Aizo (1870-1954) and Kokko (1876-1955) Soma. Photograph: Bose of Japan.

Rash Bihari Bose (1886-1945) with Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) his two children and parents-in-law Aizo (1870-1954) and Kokko (1876-1955) Soma. Photograph: Bose of Japan.Their son was killed in action during World War II while fighting Allied Forces in Okinawa but their daughter married a Japanese man and gave birth to her own daughter. But this was not the final twist in this unpredictable Indo-Japanese narrative.

-

- Revolutionary Indian Curry

I

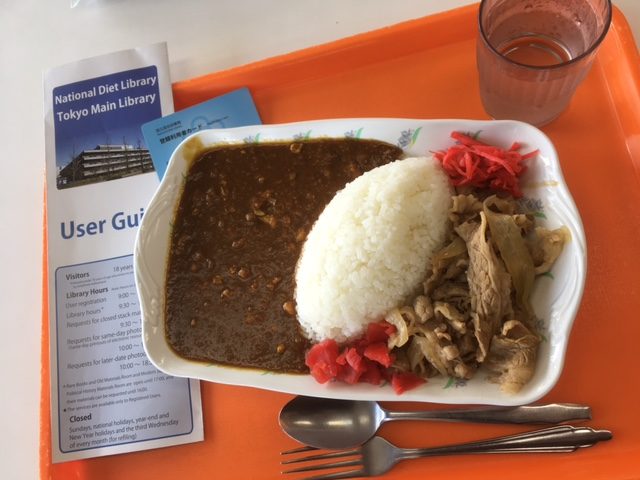

n 1872 Robun Kanagaki (1829-1894), a well-known author and journalist published a book containing the first recipe in Japanese for making curry. It was based on a British Royal Navy recipe and wasn’t authentic Indian-style curry. National Diet Library’s Library Curry – the signature dish of the 4th floor cafeteria of the library. Photo: Red Circle Authors Limited

National Diet Library’s Library Curry – the signature dish of the 4th floor cafeteria of the library. Photo: Red Circle Authors LimitedIn another spiced-up anti-colonial act in defiance of British culinary rule and British-curry’s occupation of Japanese palates, Bose, following the death of his wife, approached his father-in-law, Aizo, about selling and serving authentic Indian curry at Nakamuraya.

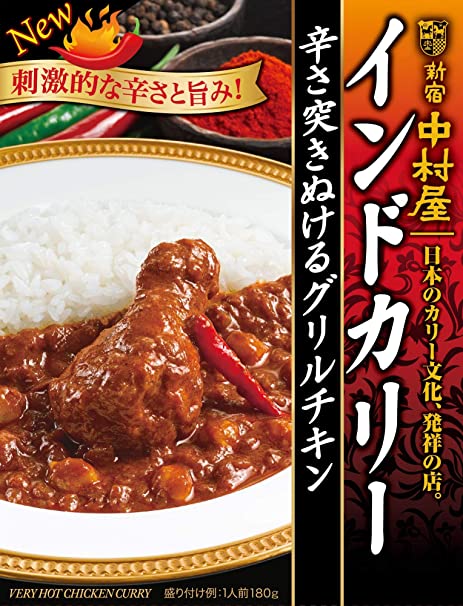

Subsequently, a plan was cooked up and an India room set up in 1927 at their café allowing the Somas to start serving Indian-style curry for the first time in Japan, which soon became known as Indo-Karii.

Bose chose the ingredients for the dish that quickly become one of their signature dishes, chicken-curry with rice and pickles. It is still served today in Japan, proving that transformative legacies can come in many forms.

-

- Pioneering Artisan Bakers: A Flavour of Things to Come?

T

he Somas and Nakamuraya continued to curry favour with Japanese consumers, by supporting and feeding people after the devastation of the Great Kanto Earthquake, and launching eye-catching new products.In 1929 they started selling branded chocolate and in 1940 they launched curry buns. All of which helped them navigate their business through the ups and downs of Japan’s Showa era and the Second World War, right up to the present day.

Unlike their brave-hearted daughter, Toshiko’s parents lived long lives, dying one year apart; her father in his 80s in 1954 and her mother in her late 70s in 1955.

Kokko who always appeared to know her own mind, died the day after she was moved into a retirement home having fulfilled her youthful writing ambitions and more. She published several books in March 1944, and February 1953. Thus ensuring that her light and narrative would never dim.

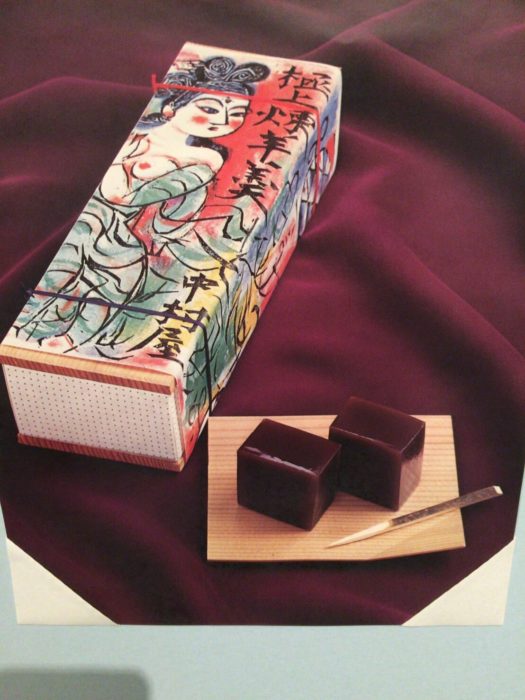

Nakamuraya Yokan package designed by Shiko Munakata (1903-1975) for Nakamuraya.

Nakamuraya Yokan package designed by Shiko Munakata (1903-1975) for Nakamuraya.Nakamuraya asked Shiko Munakata (1903-1975), an international award-winning woodblock printer, to create new package designs for their range. He drew on India for inspiration and created three different types of wrapping paper design using motifs of an Indian deity. Instead of covering the entire container, the wrapper was designed to be tied over the box housing the Yokan and be removable.

This was a first in Japan, which turned Nakamuraya’s Yokan into affordable and exotic works of art, as well as delicious snacks. Some observers have pointed out that the semi-naked back-haired deity, providing the protective wrapping for these perishable delicacies, bears more than a fleeting resemblance to Toshiko.

Package design of Nakamuraya Chicken Curry

Package design of Nakamuraya Chicken CurryAnd for almost twenty years ready-to-eat packages, also based on Bose’s original recipe, have been sold across Japan at convenience stores: extending Indian curry lineage deep into the heart of culinary Japan.

The momentum of Toshiko’s narrative shows that the products of embracing uncertainty and the strange with open-minded creative flare can be lasting, unexpected, and incredible.

-

- Unsung women from history and the future of Japan

I

f you find yourself in Shinjuku, pop into Kinokuniya, one Japan’s best bookshops, located on the opposite side of the road from the Nakamuraya building, and pick up a novel in Japanese or in translation by one of Japan’s current cohort of brilliant female writers or perhaps even one of the indomitable Kokko Soma’s books. Promotional display for all the businesses, including the Manna Restaurant, located within the Nakamuraya Building in Shinjuku Tokyo. Photo: Red Circle Authors Limited.

Promotional display for all the businesses, including the Manna Restaurant, located within the Nakamuraya Building in Shinjuku Tokyo. Photo: Red Circle Authors Limited.It is the perfect way to pay homage to Toshiko, the progressive unyielding human-shield, as well as other early Japanese pioneers and their narratives, while also savouring unusual narratives of the present, and possibly Japan’s future. You will also be sharing a culinary experience with some characters that feature in at least one Haruki Murakami novel, IQ84, and perhaps also an experience the author, like many others, has enjoyed himself.

Much has been written about Bose and the artists that frequented the Nakamuraya salon and the Somas, but the story of the Japanese girl with a book, Toshiko, who was at the apex of this network of individuals trying to change nations, has been impossible to erase from history but is sadly often forgotten or passed over.

Toshiko is just one of many unsung women from Japan’s rich history, and unsurprisingly it has taken more than a thousand words to tell her tale.

© Red Circle Authors Limited

As David Bowie sung in his song 'Changes', culture and embracing the strange be it Indian curry, art or people from afar can make a difference and change a nation or a city: "Turn and face the strange, Ch-ch-changes... I watch the ripples change their size, But never leave the stream, Of warm impermanence...".

As David Bowie sung in his song 'Changes', culture and embracing the strange be it Indian curry, art or people from afar can make a difference and change a nation or a city: "Turn and face the strange, Ch-ch-changes... I watch the ripples change their size, But never leave the stream, Of warm impermanence...".