The Maneki-neko continues to bring people good luck, not just in Japan but internationally, as well as providing inspiration for authors who have used it widely and creatively including within children’s books and even on occasion Science Fiction. Photograph: Wikipedia.

The Maneki-neko continues to bring people good luck, not just in Japan but internationally, as well as providing inspiration for authors who have used it widely and creatively including within children’s books and even on occasion Science Fiction. Photograph: Wikipedia.Japan’s obsession with and love of cats, Neko, started over a thousand years ago. They have been a rich and inspiring source for Japanese writers and artists for generations.

Japan’s cats have also received wide coverage from international journalists writing about Japan’s cat islands (where cats outnumber people eight to one); cat cafes in Tokyo; and the depiction of the feline in Japanese woodblock prints, folklore and art.

But cats aren’t just big in Japan; some Japanese cats are now international super-stars. The most famous Japanese cats are probably Maneki-neko, Hello Kitty and Doraemon. None of which are real.

Many people mistakenly think that the beckoning-cat, Maneki-neko, often displayed in restaurants and shops to bring luck, is Chinese. It isn’t.

Japanese cats pop up all over the place on book covers (The Metronome, Jennifer Maiden), in Prime Minister’s offices (Edward Heath the British Prime Minister reportedly collected them), Video Games (Pokemon, Mario) and even as urban graffiti art. Photograph: Rue De La Butte Aux Cailles, Paris. Red Circle Authors Limited.

Japanese cats pop up all over the place on book covers (The Metronome, Jennifer Maiden), in Prime Minister’s offices (Edward Heath the British Prime Minister reportedly collected them), Video Games (Pokemon, Mario) and even as urban graffiti art. Photograph: Rue De La Butte Aux Cailles, Paris. Red Circle Authors Limited.She is a Japanese original; a Japanese bobtail with an upright welcoming paw that is thought to have originated in Edo in 1852. She is said to have been the inspiration for Hello Kitty another Japanese bobtail launched into the world in 1974. Hello Kitty, technically a hybrid Japanese-British cat, was named after a cat (also called Kitty) that Alice plays with in Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass.

The international popularity of Doraemon, a blue time traveling robot cat from the late 60s, who in fact pre-dates Hello Kitty, is much more recent. Doraemon has become hugely popular in many countries across Asia, including India.

The robotic cat Doraemon was created by Fujiko Fuji. Photograph of a Doraemon doll for sale in a Tokyo gift shop. Credit: Red Circle Authors Limited.

The robotic cat Doraemon was created by Fujiko Fuji. Photograph of a Doraemon doll for sale in a Tokyo gift shop. Credit: Red Circle Authors Limited.Its newfound popularity is, however, having some unexpected consequences. A worried politician in Pakistan, for example, has launched a legal petition to have the number of hours the country’s children are exposed to this unusual cat with its special gadgets that are used – sometimes disastrously – to help the boy in the story, Nobita, get out of trouble. Apparently, this fictional cat from the future is having a “negative impact on the educational and physical well-being of children.”

Stealthy, cool Japanese cats have been slinking their way out of Japan for some time now entertaining the world in different forms and formats. They are now part of so-called Japanese Soft Power. But cats have populated the pages of Japanese literature for centuries since cats first arrived in Japan, a thousand years ago, initially to guard temples from mice.

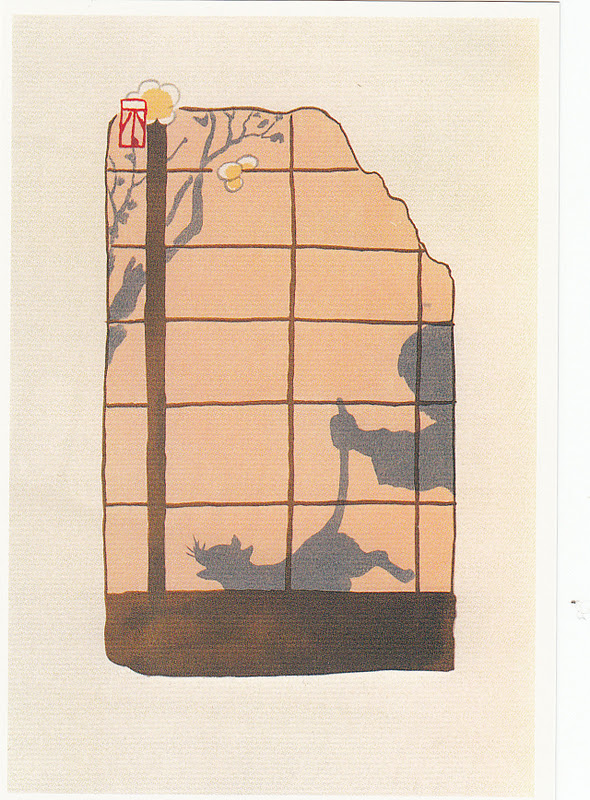

The first famous modern literary cat features in the book: I am a Cat, a highly regarded satirical account of Japan’s Meiji Era (1868-1912) written from a condescending cat’s perspective by the acclaimed author Soseki Natsume (1867-1916).

Illustration from Soseki’s book, I am a Cat, by Fusetsu Nakamura (1866-1943). Credit: Taito Ward Calligraphy Museum, Japan.

Illustration from Soseki’s book, I am a Cat, by Fusetsu Nakamura (1866-1943). Credit: Taito Ward Calligraphy Museum, Japan.Cats also helped establish the reputation of the free-style poet Sakutaro Hagiwara (1886-1942). His importance was cemented within Japanese literary circles with the poem Ao Neko, The Blue Cat, in 1923; which was followed by the short story in 1935, The Town of Cats.

Junichiro Tanizaki (1886-1965) who is held in similar regard to Soseki as one of Japan’s greatest writers, wrote the novella A Cat, A Man and Two Women in 1936. This story is about a rivalry for attention from three female characters; a cat – Lily -, an ex-wife and a new younger second wife.

Cats also often feature prominently in some of Haruki Murakami’s novels. He is on record as being a cat lover and cats play important roles in: The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, Kafka on the Shore and a story titled: Town of Cats included in IQ84, which was published in 2011. An English translation, of this thoughtful and moving story, was published in The New Yorker, in September 2011.

Naoki Prize winner, Kazufumi Shiraishi, is also known for being an admirer of the furry four legged creatures, as is Mitsuyo Kakuta who blogs about her cat.

Japan’s cat population is forecast to grow at a rate of 4 percent a year, while the number of dogs is expected to decline. Cats cost half as much to look after as dogs; and Japan’s urbanized aging and shrinking population is a factor behind these figures. However, it’s not just cats and books about them that are on the rise. The cat food market is now worth a staggering 2 billion dollars annually. Japan’s ubiquitous cats are generating an array of new business opportunities especially for creative people.

And it isn’t just the publishing world that has identified this as a targeted growth market. Mars, better known for its treats for humans, has built up the largest market share for cat food in Japan with more than 10 percent of the market. One of its leading brands is Kal Kan, which cats have been enjoying since 1936.

Cats and cat memes are abundant on the Internet in Japan like elsewhere. Despite the medium being new this isn’t really a new phenomenon. In the 1980s, there was the Nameneko craze triggered by a photo published in 1979 of cats dressed up like a Japanese motorcycle gang with the caption: “All Japan Fast Feline Federation – You Won’t Lick US!” This generated all sorts of opportunities, images and spin-offs; including Nontan, a children’s book series by Sachiko Kiyono about a naughty playful kitten, which was first published around this time, and has since expanded into 40 volumes selling millions of copies in Japan, France and China.

A much more recent Japanese cat fad is Neko Atsume (Cat Collector), an Android and IOS game that has been downloaded more than 10 million times. This means rather oddly that there are now more people collecting the 50 plus cats in the game than there are both cats and children across Japan. All this cat craziness does have side effects. There are about 60 thousand stray cats in Tokyo alone.

Nissan, the car manufacturer, has launched a public safety campaign to urge drivers to check below their cars by knocking on their bonnets for stray cats before driving off. The campaign slogan sounds like a traditional ‘Knock Knock’ joke loved by kids in the English-speaking world, but it most certainly isn’t a joke. It does make you wonder how an English speaking cat might respond if confronted with the catchy copy in these circumstances: Knock Knock, Who’s there? Hans. Hans who? HANS OFF MY CAR! perhaps.

Unlike advertising campaigns, brilliantly creative compelling cat literature is not a fad, but a long-term established trend.Unlike advertising campaigns, brilliantly creative compelling cat literature is not a fad, but a long-term established trend. Japanese authors continue to observe, write about and use cats as a metaphor for Japan’s changing society and family dynamics. The Guest Cat, published in English in 2014, is an internationally acclaimed recent example of this genre. This New York Times bestseller written by the poet Takashi Hiraide initially gained attention outside Japan in France, before being published in America and subsequently around the world in more than 15 countries. The next example in this continuing trend is The Travelling Cat Chronicles, by Hiro Akikawa in which both the cat and its owner act as the story’s narrator.

While the future for dogs in Japan looks precarious, it is still cool to be a cat; and the feline form will continue to inspire, play a major role, and flourish in books to come as Japan’s cat-loving audience of readers continues to grow.

David Bowie picked up this cat trend, as was often the case, before most. He even sang that Ziggy Stardust was "like some cat from Japan" but no doubt didn't have cute cats in mind when he wrote the lyric. Photograph: Shop window in Nakano Broadway, Tokyo: Red Circle Authors Limited.

David Bowie picked up this cat trend, as was often the case, before most. He even sang that Ziggy Stardust was "like some cat from Japan" but no doubt didn't have cute cats in mind when he wrote the lyric. Photograph: Shop window in Nakano Broadway, Tokyo: Red Circle Authors Limited.