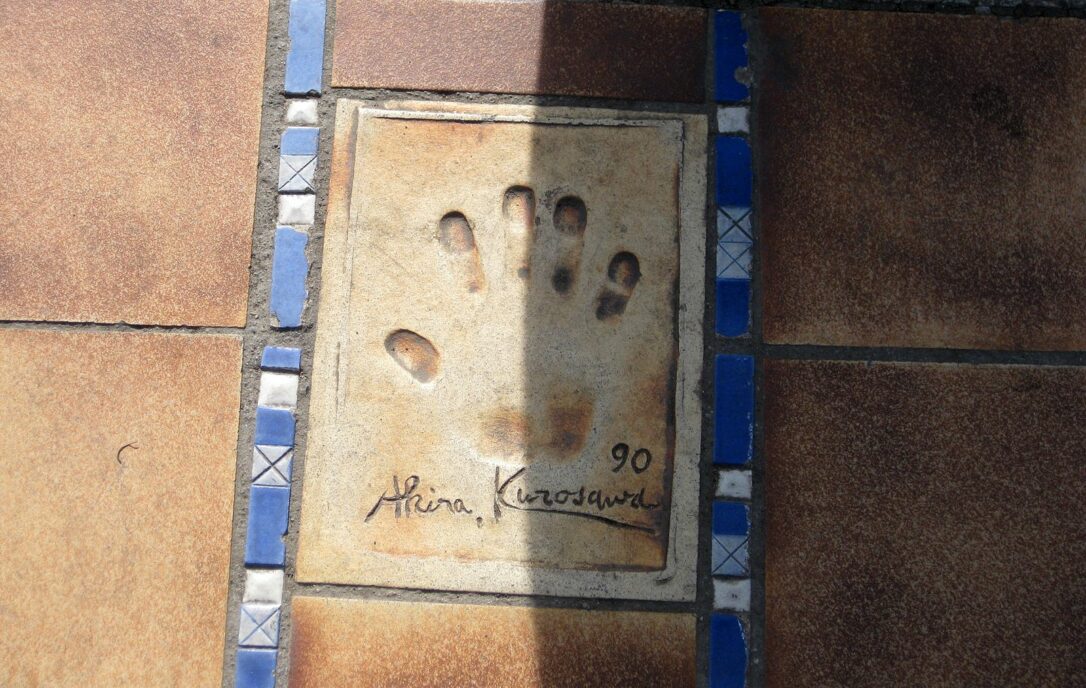

Akira Kurosawa handprint in Cannes Photo: Wikimedia Christian Muellner

Akira Kurosawa handprint in Cannes Photo: Wikimedia Christian MuellnerI

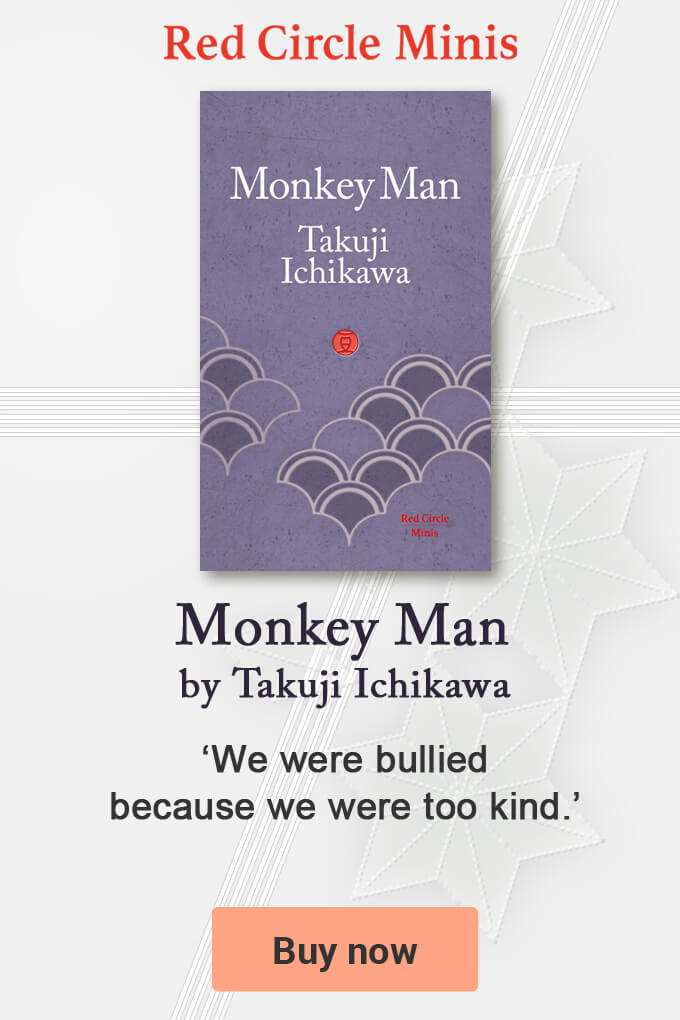

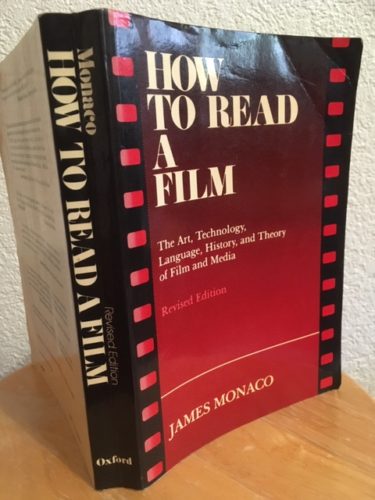

s it necessary, really, to learn how to read a film?’ asks the seminal book on film studies, How To Read a Film, in the first line of its preface. James Monaco, who wrote the first edition of this quintessential book in 1977, which has since been updated many times and now stands at 736-pages, obviously thinks so.

As do many lecturers, who recommended the book as an introductory text for students studying or interested in film, and of course his publisher, Oxford University Press.

The Revised Edition, 1981, of How To Read A Film by James Monaco. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.

The Revised Edition, 1981, of How To Read A Film by James Monaco. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.-

- Study the great novels and dramas of the world

K

urosawa didn’t go to film school. In fact, he didn’t attend any institutes of higher education, finishing formal education at the age of seventeen. He did, however, read an awful lot of books and often recommended aspiring students of film and directors, to follow his example, and read, as well as write, and direct.  Copies of a Japanese language translation edition of War and Peace (戦争と平和) by Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910).

Copies of a Japanese language translation edition of War and Peace (戦争と平和) by Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910).When he was growing up Kurosawa reportedly read everything he could get his hands on without discrimination: both the classics and contemporary fiction. It’s something that Japan’s most notorious author Yukio Mishima (1925-1970) also claims. And it’s probably true to say that books probably influenced Kurosawa’s cinematic storytelling more than anything else.

However, it seems highly unlikely that How To Read a Film was on Kurosawa’s reading list alongside works by the authors he is known to have read and admired such as William Shakespeare (1564-1616), Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821-1881), Natsume Soseki (1867-1916) and Maxim Gorky (1868-1936).

Kurosawa made his directorial debut in 1943, 34 years before Monaco’s text was published and before students started studying how to read, analyse, appraise, deconstruct and critique films.

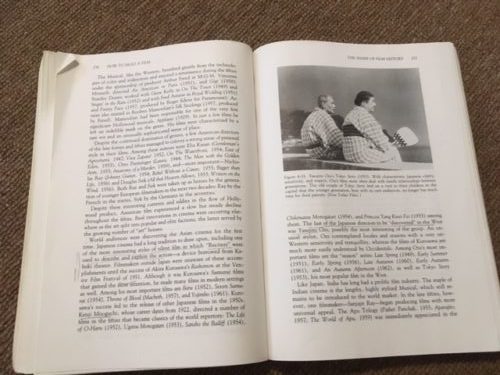

Section in How To Read A Film by James Monaco, The Shape of Film History, featuring Akira Kurosawa (1910-1998), Yasujiro Ozu (1903-1963) and Kenji Mizoguchi (1898-1956). Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.

Section in How To Read A Film by James Monaco, The Shape of Film History, featuring Akira Kurosawa (1910-1998), Yasujiro Ozu (1903-1963) and Kenji Mizoguchi (1898-1956). Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.Nonetheless and unsurprisingly, as he is considered a visionary and one the world’s greatest directors, Kurosawa does get a mention, even in the early editions, of this book, which became an instant classic when it was initially published in the 1970s.

According to Monaco, filmmakers outside Japan were unaware of the long history of Japanese filmmaking, including ‘the more interesting styles of silent films in which ‘Reciters’ were used to describe and explain action – a device borrowed from Kabuki theatre, until the unexpected success of Kurosawa’s Rashomon at the Venice Film Festival of 1951’, where it won the Golden Lion.

Interestingly, one of Kurosawa’s older brothers, Heigo, was a well-regarded ‘reciter’, benshi, at a cinema in Kanda, an area in Tokyo famous for its large number of secondhand bookshops.

Nevertheless, as motion pictures with synchronised sound, took off in the 1930s the role of the benshi became an anachronism and slowly became obsolete even in Japan. Tragically, Heigo killed himself in 1933. Three years later Kurosawa got his first job in the film industry as a trainee assistant director.

This didn’t stop him from reading or change the types books he read. Kurosawa still read pulp fiction, contemporary Japanese literature and the great Russian authors, but his approach became more analytical.

He started reading more carefully, asking himself as he read about the author’s objectives and how each author went about expressing these in words and within narrative prose. He also started making notes and importantly, he also started writing screenplays.

Promotional film poster for Sanshiro Sugata (Judo Saga) directed by Akira Kurosawa. Image: Wikipedia.

Promotional film poster for Sanshiro Sugata (Judo Saga) directed by Akira Kurosawa. Image: Wikipedia.The action film was set in the 1880s when judo was founded by Jigoro Kano (1860-1938) out of the traditional Japanese martial art Jujitsu with the help of the author’s father – one of the Four Guardians of Kodokan Judo – and other similar exceptionally proficient fighters.

The film established Kurosawa’s reputation in Japan as an exciting and important newcomer, and alongside the book, helped shape how Kurosawa portrayed fighting and fighters in his films.

Kano, like Kurosawa himself, had a major lasting impact on how the world saw Japan as a nation as well as his chosen profession. He was the first Asian member of the International Olympic Committee (IOC).

Kano helped shape many things besides his sport, which would many years later become a popular international and Olympic sport. He’d influence the Olympic movement in Japan, the nation’s so-called Olympic Literature, and indirectly Kurosawa’s career through his sparring partner’s son’s novel published in 1942, the year before Kurosawa’s first film went on general release.

-

- The art of storytelling

I

t was another Japanese author, though: Ryunosuke Akutagawa (1892-1927) that brought Kurosawa and Japanese filmmaking international attention and recognition. Akutagawa, after whom one of Japan’s most prestigious literary awards is named, is best known outside Japan for his first published short story ‘In a Grove’, which cleverly employs multiple narrative viewpoints in the form of witness statements of a single crime, a rape – giving the impression that reality is never what it first seems.

Readers of ‘In a Grove’ are left totally unsure as to the true outcome of this intriguing but compact tale. An authentic reflection perhaps of the real world in which the true nature of things cannot always be readily determined.

Akutagawa’s short stories, of which he wrote many, followed and developed the long and continuing tradition of masterful short story writing by Japan’s leading authors of each generation.

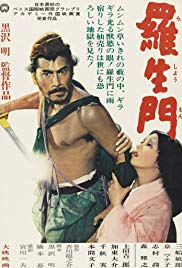

Promotional poster for Rashomon directed by Akira Kurosawa. Image: IMDb.

Promotional poster for Rashomon directed by Akira Kurosawa. Image: IMDb.Rashomon became an instant classic. It not only triggered a brand new approach, it also influenced many leading directors including the likes of Steven Spielberg, who is currently working on a television adaptation of the film.

This has all helped embed the role of the short story in Japan as an excellent source and important creative format; and masters of the modern Japanese short story; writers like the Akutagawa-nominated author Kanji Hanwa who specialises in the genre, have found their stories, sometimes with and sometimes without their consent, being used at Japanese film schools to teach scriptwriting.

Most of Kurosawa’s films were literary adaptations and he constantly argued that reading and writing were the critical components to cinematic success. He believed that memory is the source of creativity and that reading and writing creates memories, alongside living an interesting life, without which the creative process would not function.

Some academics argue that ‘reading like an author’ can have measurable cognitive benefits improving, for example, brain connectivity, as well as having more general health benefits. And this is something that Kurosawa seems to have understood instinctively.

By some measures Kurosawa is the most successful and important film director outside the English-speaking world. In 2018, the BBC conducted a survey of 209 international film critics to come up with a ranking: The 100 greatest foreign-language films.

Two of the top five ranked films were made by Kurosawa and he is the only director to have two films in the top five; Seven Samurai is ranked number one, and Rashomon number four.

Kurosawa has a total of four films included in the list ranking him, in terms of the number of films, alongside directors such as Federico Fellini (1920-1993), Andrei Tarkovsky (1932- 1986) and Ingram Bergman (1918-2007), who all also have four films in the BBC list of the top 100 foreign-language films.

Following Kurosawa’s advice on storytelling is probably, therefore, a very good place to start. He argued that it is only through writing scripts that you learn the specifics about the structure of film and what cinema is, and all you need to do that is paper and a pencil.

It is often argued that writing helps process ideas and memories, as well as develop clarity of thought. Many experts and fans have commented on Kurosaka being a champion of this and that he drew and painted how he wanted scenes in his films to look, a technique dubbed ‘Every Frame a Picture’. One talented admirer has even created a cartoon strip, tilted: Kurosawa The Note Taker portraying the importance he placed on reading and writing. This is how Kurosawa honed his craft. He wrote many scenes and scripts for the films he directed. Films like his debut movie as a director, and films he didn’t direct, like Sword for Hire, which is based on a novel by the Akutagawa prize-winning author Yasushi Inoue (1907-1991), who is also known for his novella and short stories.

Kurosawa’s approach to storytelling was to write and rewrite, drawing on his experiences as well as his emotional memories, including his literary memories from the vast number of books he had read. All of which contributed to the formation of his humanistic worldview.

Sometimes he’d loosely adapt, for instance classic works of European literature or contemporary Japanese fiction for the screen; and sometimes he’d combine and blend well-known narratives to great effect.

When asked if his works had a common thread he reportedly said they all posed a common question: “Why can’t people be happier together?”

-

- How to read like Kurosawa

S

ome individuals, not just aspiring directors, want to read like Kurosawa with the aim of mimicking or capturing his creativity; others just want to do so to understand him and his films better; and others still simply want to read about him. There are many websites and online resources to help budding aficionados, including reading lists from book recommendation sites such as Book Riot with articles and headlines like: What to Read If You Love Akira Kurosawa.

That said, Kurosawa actually talked publicly about his favourite books on national television in Japan. They were apparently: War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy, Sanshiro by Natsume Soseki, The Idiot by Fyodor Dostoevsky and The Tale of Heike, a Japanese medieval classic, which has been referred to as Japan’s Iliad.

Something Like an Autobiography, Gama no abura, Jiden no you na mono, Akira Kurosawa. Image: Wikipedia.

Something Like an Autobiography, Gama no abura, Jiden no you na mono, Akira Kurosawa. Image: Wikipedia.Interestingly, none of the books that are known Kurosawa favourites, or books that have clearly influenced the films he made, appear on Bowie’s 100 must-read books reading list.

Bowie’s inclusion of one Japanese literary author Yukio Mishima and his book The Sailor Who Fell from Grace from the Sea might have raised a comment from Kurosawa as Mishima was famously at times dismissive of Kurosawa’s films, despite or perhaps because of his own interest in appearing in films and having his works adapted for film.

Some renowned Japanese directors also criticised Kurosawa’s films as not being ‘Japanese’ but made for foreigners in a similar manner to how the works of Haruki Murakami are depicted today by some Japanese literary critics.

That said, Bowie’s exclusion of anything written by Dostoevsky, Tolstoy or Shakespeare might have also surprised Kurosawa, but he would probably have approved of Bowie’s inclusion of the Iliad in his list of must read books.

-

- Inspired and inspiring

B

rilliant wordsmiths and their narratives inspired Kurosawa probably more than anything; and he in turn has inspired multiple new generations of individuals working in film, television and other mediums. Many notable films and television dramas, including; The Virgin Spring (Ingmar Bergman), Star Wars (George Lucas), Breaking Bad (Vince Gilligan), She Has Got To Have It (Spike Lee), The Magnificent Seven (Antoine Fuqua), A Fist Full of Dollars (Sergio Leone), The Outrage (Martin Rift), A Bug’s Life (John Lasseter), to list just a few, are adaptions of or have been inspired by his films.

Impressively, when Kurosawa won his final Oscar, on his birthday in 1990, two delighted super-fans presented his award to him: George Lucas and Steven Spielberg.

-

- New literary montages: books galore

T

here have been countless books written about The Emperor, Tenno, of Japanese Film, as he was known – making Kurosawa’s publishing legacy an impressive one. Books and Kurosawa, in life and death, are a powerful combination. He wrote about his life in Something Like An Autobiography, which he penned in Japanese in 1981. Reviewers, scholars, collaborators and fans have contributed biographies, memoirs and scholarly works including, for instance, All The Emperor’s Men – Kurosawa’s Pearl Harbor and Akira Kurosawa and Interstextual Cinema, to the canon of film studies. And added to this, documentaries have also been made.

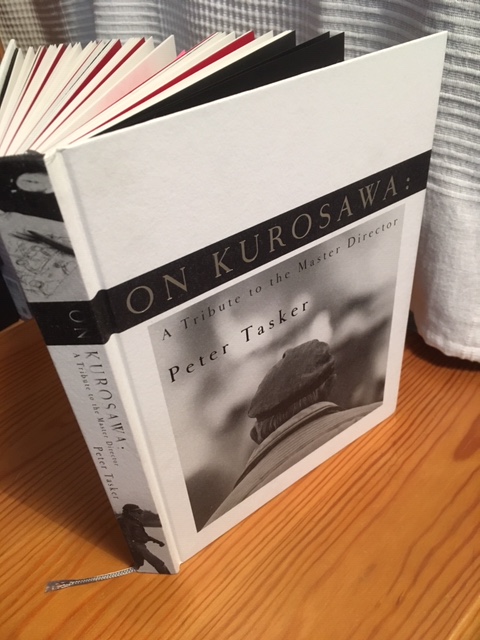

On Kurosawa: A Tribute to the Master Director by Peter Tasker, published November 2018. Photogragh: Red Circle Authors Limited.

On Kurosawa: A Tribute to the Master Director by Peter Tasker, published November 2018. Photogragh: Red Circle Authors Limited.He would also approve of the production values of Tasker’s stylish On Kurosawa: A Tribute to the Master Director, another book that, will no doubt, end up on the must read lists of aspiring filmmakers and Kurosawa admirers.

Nonetheless, Kurosawa would probably encourage such individuals to focus their reading on fiction that explores humankind in all its many forms, rather than non-fiction or film literature even if it is about him. And a good place to start is probably with Japanese short stories and novella, the formats that helped propel his career to a global level.

-

- New novelisations and J-cuts

B

ooks by contemporary Japanese authors, including Fuminori Nakamura who had three adapted for film in Japan last year alone and Mitsuyo Kakuta whose books have ended up as unmissable television dramas and films, are still a rich creative reservoir that are regularly exploited locally. Digital technologies and streaming, are generating new demand and opportunities for diverse creative storytelling in traditional formats. Who knows what future undiscovered creative cuts and blends lie in store?

Following Kurosawa’s example of reading, mixing, merging and repurposing Japanese fiction (no matter where you or your audience is based) seems to be the perfect starting point for filmmakers. Not just to learn how to ‘read a film’ but to read the market and its opportunities in novel ways that will surprise and inspire a new generation of film buffs and international audiences.

© Red Circle Authors Limited

Kurosawa Film Studio building in Kirigaoka, Midori ward, Yokohama Photo: Kubo Michal

(Wikiimedia)

Kurosawa Film Studio building in Kirigaoka, Midori ward, Yokohama Photo: Kubo Michal

(Wikiimedia)