Watching the Tokyo Olympics on TV from the street in Tokyo. 街頭テレビで東京オリンピックを観戦する市民 ( Project Kei) Wikimedia

Watching the Tokyo Olympics on TV from the street in Tokyo. 街頭テレビで東京オリンピックを観戦する市民 ( Project Kei) WikimediaI

n 1964 the Beatles song I want to Hold Your Hand topped the bestselling charts in the United States and The New York Times Fiction Best Seller of the year was The Spy Who Came in From the Cold, by the former British spy turned author, John Le Carré. Four Japanese authors were amongst the candidates nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature: novelists Junichiro Tanizaki (1886-1965), Yasunari Kawabata (1899-1972), Yukio Mishima (1925-1970); and poet Junzaburo Nishiwaki (1894-1982).

None of them won; it was Jean-Paul Sartre’s (1905-1980) winning year, but he shrugged it off, and refused to accept the prize – not wanting to become an ‘institution’.

Tokyo 1964 Gold Olympic Medal. Image: Public Domain

Tokyo 1964 Gold Olympic Medal. Image: Public DomainIn 1964, there were many memorable firsts including the first Olympic Games hosted in Japan and Asia, which despite being a summer Olympics, started on 4 October.

It was the first games at which a computer was used to store and display event results; the first to employ a live satellite link to broadcast some aspects of the games to the United States; and the first to boast colour television broadcasts in Japan.

Judo became an Olympic sport, and women’s sports were finally expanded to include team sports like volleyball. Joe Frazier, the future heavyweight champion of the world, came to worldwide public attention for the first time winning a boxing gold medal, despite only attending as the replacement for the injured fighter, Buster Mathis.

- More than a Game

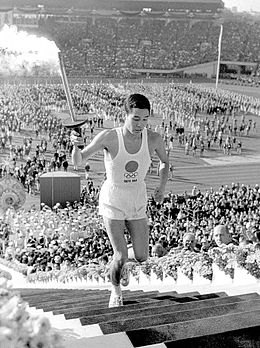

Yoshinori Sakai (1945-2014) the last torchbearer at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics running up steps on his way to lighting the cauldron. Photograph: Wikipedia.

Yoshinori Sakai (1945-2014) the last torchbearer at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics running up steps on his way to lighting the cauldron. Photograph: Wikipedia.A

young Japanese athlete named Yoshinori Sakai, the last torchbearer, lit the Olympic cauldron. His presence was hugely symbolic. For Sakai, dubbed the ‘Atomic Bomb Boy’, was born just outside Hiroshima on 6 August 1945, the fateful day on which the first atomic bomb was dropped. As the world’s media saw he was young, and undamaged by the past; and, like Japan, had a bright future ahead.

Japan was now the sporting capital of Asia, and Tokyo its most advanced city. Japan was back with a vengeance. This was the narrative that the Japanese government wanted the world to see as Japan was showcased like never before.

Japan’s national airline, Japan Airlines, made its own special contribution to the campaign to show that Japan was special, and its outputs unique, aspirational and stylish. It launched a Haiku competition with an American radio station.

This helped popularise this ancient short form of poetry and taught Americans about Japan’s literary culture and history. No fewer than 41,000 poems were submitted – giving rise to what is sometimes now dubbed Haiku-diplomacy. It continues to this day.

Haiku contests are no longer rare. They have become both numerous and international, and Haiku is now very popular, even with international statesmen, who pen poems in their own languages. The Financial Times has even run a competition; and winning school children, like Olympic athletes in 1964, sometimes find themselves flown to Japan.

- Films and books set new records

M

eanwhile, Japan’s leading authors were focusing their efforts on their own narratives and publishing important books that explored various themes that reflected their authors’ personal insights into the state of the nation and the Japanese psyche. This was a portrayal that wasn’t necessarily aligned with the image the Japanese government was keen to convey. Yukio Mishima, for example, who famously killed himself six years after the Olympics, had become frustrated with the direction in which his country was moving, and published a novel in 1964 entitled Silk and Insight. The book is a social commentary focusing on an industrial strike that took place at a Japanese silk textile plant, and highlights the shifting industrial relations occurring in Japan at that time.

The Face of Another by Kobo Abe originally published in Japanese in 1964 was adapted for film by Hiroshi Teshigahara (1927-2001).

The Face of Another by Kobo Abe originally published in Japanese in 1964 was adapted for film by Hiroshi Teshigahara (1927-2001).A plastics scientist loses his face in an accident and his disfigurement is such that he is compelled to create a new one for himself. But his new identity changes his perspective, and his relationship with others – including his wife, who he manages to seduce exploiting his new facial identity.

The two future Japanese winners of the Nobel Prize in Literature would also publish new important works in 1964, and an important future literary star was born.

Yasunari Kawabata, who in 1968 became the first Japanese winner of the prize four years after the Olympics, published Beauty and Sadness, a novel that cleverly blends tradition and modernity as well as age and youth.

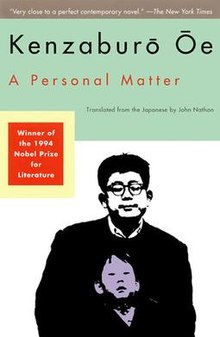

And Kenzaburo Oe, born in 1935, published A Personal Matter, which was cited by the Nobel Prize committee when he won in 1994. Interestingly, Oe, not someone known for his interest in sports, was one of the lucky ones who attended the Olympic Opening Ceremony in Tokyo, and his attendance surprised many.

Cover of the US edition, published by Grove Press, of A Personal Matter by Kenzaburo Oe translated by John Nathan.

Cover of the US edition, published by Grove Press, of A Personal Matter by Kenzaburo Oe translated by John Nathan.Other dark social commentaries published in 1964 include Abe’s novel The Woman of the Dunes, a jarringly dry novel about the futility and repetitiveness of modern Japanese existence, which was his first novel published in English. A film adaptation of the novel also went into general release.

The film, directed by Hiroshi Teshigahara (1927-2001), subsequently won the special Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival in 1964.

These narratives from some of Japan’s most intelligent and astute observers created international ripples among the world’s creative and cultural community. The highly respected Russian director Andrei Tarkovski (1907-1989), for example, listed The Woman of the Dunes as one of his all time favourite films.

Tokyo 1964 memorial plaque in Shibuya, Tokyo. Image: Red Circle Authors Limited

Tokyo 1964 memorial plaque in Shibuya, Tokyo. Image: Red Circle Authors LimitedTsutomu Mizukami (1919-2004) best known for Temple of the Geese, Hiroyuki Agawa (1920-2015) best known for Citadel In Spring, Sawako Ariyoshi (1931-1984) best known for The Doctor’s Wife, and Mishima all contributed their thoughts including those on the so-called ‘Oriental Witches’ (the nickname given to the Japanese women’s volleyball team, who won the first ever Olympic gold medal in this event by beating ‘the mighty Soviets’)’.

The final, including Miyamoto serving for the match, after multiple match points, in the final set (which they won 15-13) and their coach’s emotional reaction, are captured, retold, and documented beautifully in Kon Ichikawa’s (1915-2008) documentary, Tokyo Olympiad. The final was watched by 90%, of the population, many on newly purchased colour television sets.

Aside from Japanese publishers and the country’s government, Western authors and film directors were also keen to get on the Tokyo Olympic bandwagon, by featuring Japan’s Olympic infrastructure for settings in books and films.

The former British spy turned author, Ian Fleming (1908-1964) published his final 007 novel with precise Olympic timing. You Only Live Twice was serialized in ‘Playboy’ in the months leading up to the Tokyo Olympics. Its famous protagonist, having lost his wife Tracy, travels to Japan to save his failing career. Bond hopes Japan will provide him with a phoenix-like transformation. Interestingly, that very same year saw the publication of Fleming’s classic children’s book Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang: The Magical Car, which he wrote for his son.

The film version of You Only Live Twice was released after the Tokyo Olympics. It was adapted for the screen by the children’s author Roald Dahl (1916-1990), who penned a string of classics including Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

This was Dahl’s first film script, and features Tokyo’s new architecture and the country’s exotic though welcoming ambience. In the film Bond has a special makeover and becomes Japanese, while also fathering a child with a Japanese woman.

Another film to feature Japan at this time was Walk Don’t Run, a romantic comedy starring Cary Grant (1904-1986) in what would become his last feature film.

The narrative revolves around the shortage of accommodation that led to hundreds of individuals and athletes in Japan at the time of the Olympics having to share apartments with strangers. These chance encounters, judging by the film, created unexpected opportunities for romance. Here again, we see Japan depicted as a modern, welcoming nation.

The world of Japanese design would also become a direct beneficiary of the games. The Olympic Gymnasium, designed by Kenzo Tange (1913-2005), received a special citation and award from the International Olympic Committee (IOC) for being ‘certainly one of the finest sports buildings in the world’.

The Olympic posters, designed by Yasaka Kamekura (1915-1997), most of which featured dramatic photographs of athletes in action, were also very well received.

A hundred thousand copies of the first poster, which was one in a series of four, featured a simple red circle designed to ‘renew the appreciation of the Rising Sun’s dynamic simplicity’.

The British Museum in London even acquired one for its collection, and the posters went on to win the Milan Poster Design Award.

The poster titled: ‘The Start of the Sprinters Dash’, which dramatically captured the first seconds of a race, was hailed as a milestone in graphic design.

In the official literature after the games Avery Brundage, president of the IOC wrote: ‘even the most callous journalists were impressed, to the extent that one veteran reporter named them the “Happy Games”‘. Brundage argued in the official Olympic report that Japan had demonstrated its ‘capacity’ and was the ‘Number One Olympic Nation today’.

Japan also won 29 medals including 16 gold medals, more than any other Asian nation, behind only the United States and the Soviet Union.

Japan’s strategy, to rebrand the nation, had worked brilliantly. Many predicted momentum would continue and Japan’s future would be prosperous and full of promise.

- A Rite of Passage: New Summer Olympic Fruit

T

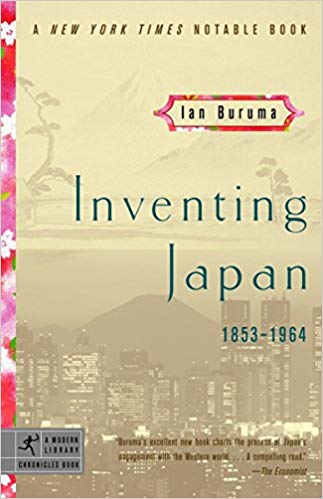

he games brought the nation together – instilling pride, national identity and unity for the first time since the war. An extraordinary 28.7 million people came out onto the streets to watch the Olympic torch relay, which took 91,237 ‘man-days’ of police and traffic officials’ time to manage safely.  Cover of Ian Buruma’s “cool, informed historical primer”. Published in 2003.

Cover of Ian Buruma’s “cool, informed historical primer”. Published in 2003.Ian Buruma, a Japan expert and journalist, who is now editor of The New York Review of Books, is one such individual. His short book Inventing Japan: 1853-1964 charts more than a hundred years in fewer than 200 pages.

It traces the history and transformation of Japan from a feudal society forced open by Commodore Perry’s American ‘black ships’ in 1853 to the Olympics – at which point Japan had become an economic dynamo and a fully industrialised democratic society.

Some even employed the halo-effect and momentum of the Olympics to speculate about Japan’s future. The Tokyo Olympics marked a turning point from which the Japanese economy continued to grow apace. In fact, by 1968 she had become the world’s second largest economy.

- All good stories come to an end

W

hile Japan grew in confidence, its brands and products reached most corners of the world; and its companies built factories overseas. Some commentators even went as far as suggesting that the Japanese economy would eventually overtake that of the United States. A book, Japan as Number One: Lessons for American, by Eza Vogel, an eminent Harvard professor, helped corroborate this theory in 1979. However, economic trends do not generally continue in a straight line. The momentum of the Olympics and the euphoria and economic surge that it set in motion could not be sustained forever.

In such circumstances, it often takes a provocateur to point out the obvious, and in this case it was the brilliant surrealist and science fiction author, Yasutaka Tsutsui, who did so. Tsutsui, born in 1934, subtly poked fun at the Olympics in his 1971 short story, Running Man.

The story is set in the future, and features automated restaurants run by robots; and marriages arranged by computer-matching that analyses both physical and personality compatibility. Nobody is the least bit interested in the Olympics. Most have completely forgotten about them, all Olympic momentum has been lost and some don’t even know what the word means.

In Tsutsui’s fictional world most people are lazy, uninterested in sports or competition, and many die young. Nobody really knows why someone would bother running a marathon. Nevertheless, one man decides to join the Olympic marathon, a race with only two other competitors, which takes him most of his life to complete. And once he does and wins, he isn’t treated to applause or a glorious medal ceremony, because nobody knows or cares about his achievement.

Japan’s economic expansion, like The Cold War, ended dramatically. Uncontrolled growth caused the economy to inflate into one of the world’s largest recorded economic bubbles. Most people in Japan simply didn’t read the signs, or were uninterested when they were pointed out. The bubble, which had inflated in 1980s, reached its greatest size in 1991, and then dramatically collapsed in 1992, the year after the Soviet Union collapsed and dissolved into a cluster of new republics.

The bursting of the bubble caused another period of devastation in Japan. The economy measured by GDP per capita fell by more than 30% in one year from peak to trough. The narrative about Japan in the world’s newsprint shifted once more. The glorious Olympics were soon forgotten, and headlines like The Land of the Setting Sun, became the order of the day.

- Post Olympic narrative

T

he new generation of authors did not completely ignore or forget Japan’s Olympic turning point, and its bitter fruits. Several wrote brilliantly about the bitter Olympic experience, often in a very different style to Japan’s early Olympic literature and its first Olympic novel written by a rower in 1940, Hidemitsu Tanaka (1913-1949), Orinposu no Kajitsu, The Fruits of Olympus. The Akutagawa Prize-winning author Miri Yu, born in 1968, is one such author. Her 2014 novel JR Ueno Park Entrance is the tale of a man who moves to Tokyo from Fukushima to support his family at the time of the 1964 Olympic Games.

Thirty-seven years after his arrival at Tokyo Station, he finds himself back there, this time living in a homeless camp in a park near the station’s entrance. He is ‘used and discarded’ a decade after the Japanese economic bubble had collapsed. His story mirrors the arc, the developmental rise, missed opportunities and the lows that the Japanese economy experienced and the lives that many were obliged to live.

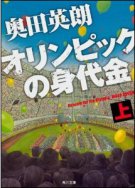

Cover of first volume of Olympic Ransom by Hideo Okuda published by Kadokawa in 2008.

Cover of first volume of Olympic Ransom by Hideo Okuda published by Kadokawa in 2008.The book’s protagonist is a desperate young Japanese man from a poor family, whose older brother supports him financially. Following his brother’s tragic death on a construction site of one of the many new Olympic venues, our protagonist decides to dramatically ruin the nation’s Olympic plans.

Sadly, construction of the sites for the 2020 Olympic Games are causing fatalities today. One 23-year-old man, for instance, reportedly killed himself after working 47 hours of overtime every week for a month on the new Tokyo Olympic stadium.

Given this and the fact that Tokyo has experienced local terrorism in the form of the 1995 nerve gas attacks on the Tokyo subway, the plot of Okuda’s novel has a frightening authenticity about it.

- Pictures vs words

S

ome now believe that the recent popularity and success of sports manga like Slam Dunk (basketball), and Captain Tsubasa (football), which have been broadcast in anime format in 60 countries and boast some of the world’s best known footballers as fans, is starting to crowd out more traditional Japanese sports literature. The typical narrative of these heroic manga revolves around an individual becoming a hero by overcoming every conceivable challenge through extreme hard work, diligence, building strong and special friendships, as well as learning new skills en route to a glorious victory.

Fashions obviously change, but by and large these stories are the type that most parents would want their children to grow up on. While it is no doubt easier to depict some sports, especially team sports, with complex rules and subtle skills, in visual formats like manga and anime than in book form, it has to be said that there are probably few Japanese authors who are actually sports fans or enthusiastic followers of the Olympics.

Cover, bunko edition, of Dive by Eto Mori published by Kadokawa Shoten in 2006.

Cover, bunko edition, of Dive by Eto Mori published by Kadokawa Shoten in 2006.One such novel, Dive, by another prize-winning author, Eto Mori, born in 1968, concerns a diving club that lacks funding and will only win new financial support if the coach gets at least one member of the club into the next Olympics.

The book was a springboard for a very successful series targeting young adults, and has inevitably been adapted for manga and film. It follows the stories of three young male divers and their female coach competing for a place at the Olympics.

It has an Olympic-focused sports narrative that reflects the times and is likely to resonate with athletes and coaches in Britain and other countries under similar financial pressures.

There have also been several Japanese books and short stories devoted to the subject of running, a sport that has long enjoyed an interesting history in Japan as well as at the Olympics.

- The Second Coming: A Creative Rebirth

I

f 1964 represented a reacceptance of Japan by the world community; the end of its post-war period, and its resurgence as a ‘normal’ democratic nation, then the 2020 Olympics could, many believe, come to represent another opportunity for Japan to draw a line under its recent past, its so-called post-bubble lost decades. In some respects, Japan still leads the world and Asia. Tokyo, for instance, has more restaurants and famously more with Michelin stars than any other, including Paris. Its food and sushi in particular is loved the world over, and more and more Japanese words are finding their way into other languages; karaoke, judo, tofu, manga, yuzu, wasabi, emoji and anime to list just a few. To cap it all, one of its authors is even the best selling author in China and many other Asian countries.

Second-hand books on sale at a Tokyo bookshop. Image: Red Circle Authors Limited.

Second-hand books on sale at a Tokyo bookshop. Image: Red Circle Authors Limited.As far as the performing and visual arts are concerned, it is the world’s second city when measured by cinema attendance and the number of foreign films released.

It has the third largest number of theatres and major concert halls after New York and Paris. Tokyo is also the second largest city in terms of the population of students studying art and design.

Unsurprisingly, it has more games arcades than any other city, and the list could go on. With this amount of cultural energy, you would expect the next Olympics to have a significant creative and literary impact, locally and internationally.

It’s understandable why many Japanese commentators now take the view that Tokyo should promote itself as the Asian capital of culture, rather than projecting itself as it did in 1964 as Asia’s sporting capital. There is also a prevailing view that much can be gained by showing off and contrasting Japan’s refined soft-power to her neighbour’s ‘sharp power’ – and thereby conveying Japan as Asia’s cultural and democratic hub.

This said, there are many facets to Japan, and the cacophony of opinion grows ever louder as 2020 looms large. Some argue that Japan should focus on its existing Cool Japan campaign promoting popular culture, video game characters and sushi, all of which are already popular internationally. In marketing parlance, this would in effect be consolidating one’s brand image.

Others favour positioning Japan as a sports tourism destination, and fulfilling the strategy of increasing inbound tourism. Others still see their country as a haven of technological innovation, gadgets and robots, and argue that the nation should show off new high-resolution broadcasting and electronic gadgetry like self-driving taxis.

Many, of course, hope that the Olympics will enhance Prime Minister Abe’s economic policy with its so-called three arrows of monetary easing, fiscal stimulus and structural reforms – restoring Japan as Asia’s shining beacon. Tokyo and its governor are eager to promote Tokyo’s environmental credentials and sell the city as the perfect business location for new industries such as FinTech and Robotics.

Discover Tomorrow, the slogan displayed on the final frames of the Tokyo promotional candidate video used at the time of the city’s bid for the games, probably provides the best indication of what is being planned.

All said, one thing is for certain: Japan’s brilliant current new generation of authors will have a much keener eye for observing the current state of the nation and the real impact of the Olympics than government officials or media commentators who are required to constantly fill our screens with opinion without the time to think, observe, research, and process what is happening around them.

Hopefully some authors will also focus on the athletes themselves and their narratives, and not just the nation’s.

We will not know until the Opening Ceremony in July 2020 how Japan will try to position and rebrand itself. No matter what approach is finally adopted, be it a single or multi-facetted one, there will be many firsts at these games including Karate, which like Judo and Keirin, both Japanese sports, will become an Olympic sport.

Perhaps one of Japan’s brilliant current cohort of creative writers will author a new title, one fit to help carry off the Nobel Prize in Literature in years to come. Judging by the quality of today’s impressive output, it could very well be a Japanese woman. Now, that would be an exciting and important new first, and a truly memorable Olympic legacy.

© Red Circle Authors Limited

Photo: Dick Thomas Johnson (Wikimedia) https://www.flickr.com/photos/31029865@N06/51215385744/

Photo: Dick Thomas Johnson (Wikimedia) https://www.flickr.com/photos/31029865@N06/51215385744/