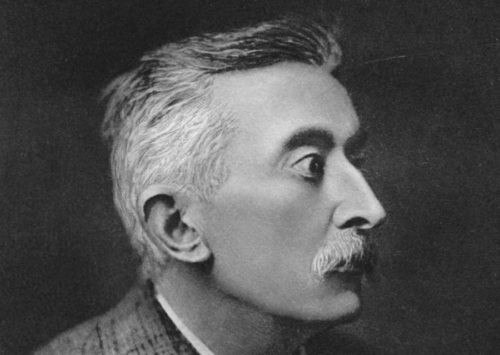

Lafcadio Hearn also known by his Japanese name as Yakumo Koizumi (1850-1904).

Lafcadio Hearn also known by his Japanese name as Yakumo Koizumi (1850-1904).“P

ray remember that your ancestors were the very Goths and Vandals who destroyed the marvels of Greek art which even Roman ignorance and ferocity had spared… You cannot make a Goth out of a Greek, nor can you change the blood in my veins.” These half-jesting words appear in a letter that Lafcadio Hearn wrote to his Cincinnati friend, the musicologist H. E. Krehbiel, in 1880. They attest, as does much else in this fascinating volume of memoirs and letters, to the fundamental importance of Hearn’s Greekness to his life and work.

Ten years later Hearn was sent on a journalistic assignment to Japan. He never returned. He married a Japanese woman within nine months of his arrival, took Japanese nationality and the Japanese name of Yakumo Koizumi (“Eight-clouds Little-spring”).

For the remaining fourteen years of his life, Hearn favoured traditional Japanese clothes, ate mostly Japanese food – though he enjoyed the occasional steak – and lived in Japanese-style houses. His funeral took place at a Buddhist temple in the Ichigaya district of central Tokyo. By then, Hearn had earned international fame as an interpreter of Japanese culture – indeed, he remains the most celebrated “Japanologist” of all time.

Lafcadio Hearn also known by his Japanese name as Yakumo Koizumi (1850-1904).

Lafcadio Hearn also known by his Japanese name as Yakumo Koizumi (1850-1904).Another early Hearn fan was future Indian independence leader Jawaharlal Nehru. Albert Einstein visited Japan hoping to find the picturesque Japan he had read about in Hearn’s books, as did Charlie Chaplin. In 1921, German philosopher Theodor Adorno wrote a play based on a Hearn short story.[1]

The key to the story of Lafcadio Hearn’s engagement with Japan lies in his origins. What entranced him about Japan, to the extent that he merged himself into the culture as completely as he could, was that it reminded him of Greece, more specifically of the mental picture of ancient Greece that he had constructed over the decades.

-

- Looking For Penelope

P

atrick Lafcadio Hearn – he was to dump his first name fairly promptly – spent most of his life as an Odysseus-like wandering exile. Appropriately, legend associates the island of Lefkada, where he was born and from which his middle name derives, with Homer’s Ithaca and Odysseus’ palace. His father was an Anglo-Irish army surgeon, his mother a striking local beauty. The family left Greece when Hearn was six and relocated to his father’s home under the not-so-blue skies of Dublin. The marriage failed and his mother soon returned home. Hearn’s father married again and put out his two sons for adoption with separate relatives.

The seven year old Lafcadio never saw his mother, father or younger brother again.

Even worse, his new home in the English countryside exposed him to a harsh brand of Roman Catholicism. Sermons about wickedness and the torments of hellfire were regular fare. In reaction, Hearn gravitated towards atheism, aestheticism and Hellenic art, later to become the pillars of his identity as a man and a writer.

Hearn’s friend and long-term correspondent Mrs. Bisland quotes this reminiscence –

“I have a memory of a place and a magical time when the sun and moon were brighter than now. Whether it was of this life or some life before, I cannot tell, but I know the sky was very much more blue and closer to the world… Everyday there were new pleasures and new wonders for me. And all that country and time were ruled by One who thought only of ways to make me happy.”

“The One” is, presumably, Hearn’s Greek mother, to whom he ascribed all his virtues, even his command of language, although she spoke very little English.

“My love of right, my hatred of wrong, my admiration for what is beautiful or true… my sensitiveness to artistic things which gives me what little success I have – even that language-power whose physical sign is in the large eyes of both of us – came from Her. It is the mother who makes us.”

Arriving in Japan, Hearn finally came home. Waiting for him was a Japanese Penelope, a Mama-san who reminded him of his own long-lost Mama-san. In a conversation recalled by his widow, he described his real mother as follows –

“She was of little stature, with black hair and black eyes, like a Japanese woman. How pitiable a Mama-san she was! Unhappy Mama-san – pitiable indeed.”

Setsuko Koizumi (Mrs. Hearn) was seventeen years younger than her husband, but he was dependent on her as language teacher, guide to Japanese customs and, not least, provider of material for his books. In her memoir, she describes how Lafcadio would ask her to tell him stories, insisting that she use her own words.

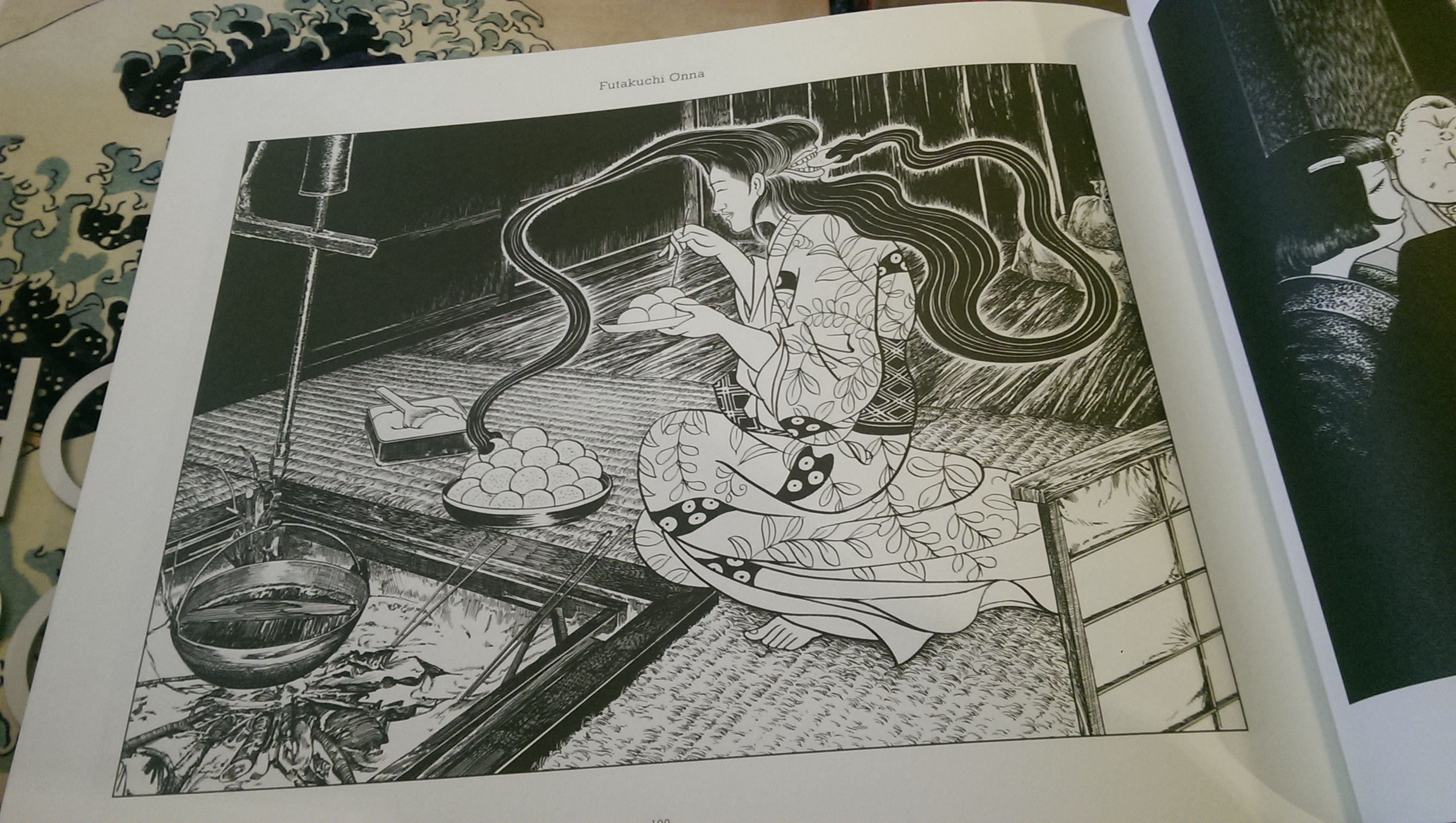

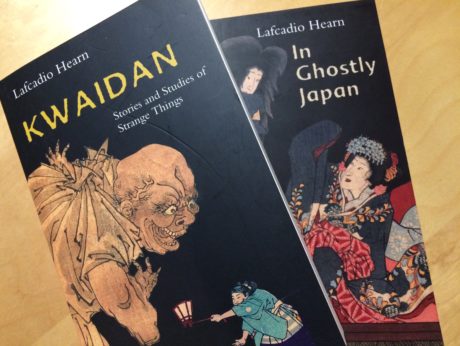

“After lowering the wick of the lamp I would begin to tell ghost stories,” she recounts. “Hearn would ask questions with bated breath, and listen to my tales with a terrified air.” Presumably, some of these spine-chilling yarns later appeared in Kwaidan and other works.

Covers of books by Lafcadio Hearn. Photograph: Peter Tasker

Covers of books by Lafcadio Hearn. Photograph: Peter Tasker-

- Down and Out in London and New York

B

efore his arrival in Japan, Hearn had been a journalist whose specialty was lushly-written travelogue and arts pieces. A small, slight man of fragile health, he had lost the sight of one eye in a sporting accident while at boarding school in England and the sight in the other was poor. With no family or connections, he had been on the breadline in London before moving to New York at the age of nineteen. Eventually, he found newspaper and magazine work in Cincinnati. There he showed his courage and disdain for convention by marrying a black woman in defiance of the local miscegenation laws.

The marriage did not last and Hearn drifted down to New Orleans which provided a more congenial environment for his artistic knowledge and sophisticated pen. It is likely he would have passed his days in obscurity if he had not been sent to Japan. Only after becoming Yakumo Koizumi did Lafcadio Hearn become Lafcadio Hearn.

Commemorative stamp issued on the 100th anniversary of Hearn’s death

Commemorative stamp issued on the 100th anniversary of Hearn’s deathIn 1904, the year of Hearn’s death, Japan declared war on Russia and was to score a stunning victory the following year, marking the first defeat of a Western power by Asians since the time of Genghis Khan.

Hearn was out of sympathy with modernisation and industrialisation. While Japan was moving in one direction, he was moving in the opposite way – back into the ancient past. The modern world appalled him, whether in New York or Tokyo, both of which he considered to be “hells.” He preferred to travel by rickshaw than train, refused to have a telephone installed and disliked Japanese people speaking English.

Despite being an enthusiastic proponent of Herbert Spencer’s extension of Darwinism, he was more conservative about Japanese culture than most Japanese of the era. There are many beautiful things in Japan,” he told his wife. “Why do they imitate Western things?” The answer, as he well knew, was in order not to be invaded, exploited or treated as “backward.”

What Hearn saw in rural Japan was a tribal society where social morality was so engrained that it did not have to be codified in laws or holy books; where, in the ultimate egalitarianism, all the dead became gods; where the people were “as primitive as the Etruscan” before the founding of Rome.

In other words, he was back in the Greek island of Lefkada with his long-lost mother, not in the 1850s, but in the era of Homer’s Ithaca, when the sun and moon were brighter than now and there were new pleasures every day.

-

- Hearn’s Warning

H

earn’s ability to cross borders emotionally and intellectually was extraordinary in his own time and remains inspirational today. His collection of Japanese ghost-stories, Kwaidan, has received the compliment of being filmed by one of Japan’s leading post-war directors, Masaki Kobayashi. Hearn’s Japan: An Interpretation is a remarkable analysis of the spiritual roots of Japanese culture.

Furthermore – and this is often overlooked – the last section, entitled Industrial Danger, contains a clear-eyed warning of the risks of Japan’s headlong rush to modernise. “Should wretchedness be so permitted to augment that the question of how to keep from starving becomes imperative for the millions, the long patience and the long trust may fail….the Primitive Man, finding that the Moral Man has landed him in the valley of the shadow of death, may rise up to take the management of affairs into his own hands and fight savagely for the right of existence.”

This is more or less what happened in the 1920s and 1930s when Japanese democracy collapsed and the Showa Depression ushered in a period of “government by assassination” and, eventually, militarist control. Hearn was fully aware that Japan’s vulnerability was political.

“The absence of individual liberty was the real cause of the disorders and the final ruin of the Greek societies…The absence of individual freedom in modern Japan would certainly appear to be nothing less than a national danger. For those very habits of unquestioning obedience and loyalty and respect for authority which made feudal society possible are likely to render a true democratic regime impossible.”

Hearn’s acuteness extended to the international situation. He was intensely anti-imperialist, alluding to events such as the Boxer rebellion as follows.

“Ancestor-worshipping people have been slaughtered, impoverished or subjugated in revenge for the uprisings that the missionary intolerance provokes. But while Western trade and commerce directly gain by these revenges, Western public opinion will suffer no discussion of the right of provocation or the justice of retaliation…”

Then, in a critique of what today might be called moral imperialism –

“The whole missionary system, irrespective of sect and creed, represents the skirmishing force of Western civilization in its general attack upon all civilizations of the ancient type… The conscious work of these fighters is that of preachers and teachers; their unconscious work is that of sappers and destroyers.”

Christian missionaries are not the force they were; today the Western impulse to preach and teach manifests itself through other channels.

In her memoirs, Mrs. Hearn observes of her husband “I think he liked always Japan better than the West and a dream-world better than this world of reality.”

Lafcadio Hearn knew all about “this world of reality” at an early age – family disintegration, religious fanaticism, physical handicap, being down-and-out in Victorian London, racism in America. He was well aware of what human beings are capable of, hence the warnings.

The dream-world he described was as mythic as the Middle Earth of J.R. Tolkien – who fought in the Battle of the Somme – or King Arthur’s Camelot or Odysseus taking the long way home. That is why his books continue to be read today, while so many dry-as-dust academic studies are quickly forgotten.

[1] See Rie Askew, “The Reception of Lafcadio Hearn Outside Japan”, New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies, (December 2011), pp 44-71.

© Red Circle Authors Limited

Peter Tasker: Special Contributor

Peter Tasker is a Tokyo based analyst and commentator on Japan and author of multiple Japan related books (fiction and non-fiction) including, most recently, "Japan’s Choices", which he wrote jointly with Bill Emmott, the former editor of The Economist. He currently works at Arcus Investment a company he co-founded.This article was originally published on PeterTasker.Asia and as an introduction to the Greek edition of The Life and Letters of Lafcadio Hearn by Elizabeth Bisland and Remembering Lafcadio Hearn by Setsuko Koizumi

Hearn with his wife, Setsuko (1868-1932).

Hearn with his wife, Setsuko (1868-1932).