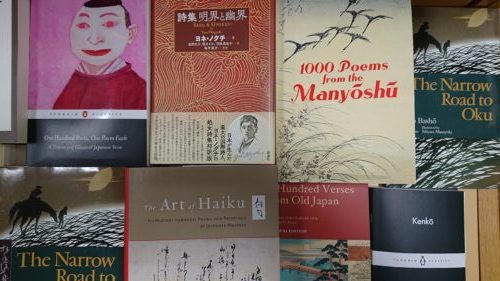

Books of English translations of Japanese poetry on sale at Kinokuniya in Tokyo, including Manyoshu, Japan’s oldest poetry anthology, from which the name of the new imperial era, Reiwa, is derived. Photo: Red Circle Authors Limited.

Books of English translations of Japanese poetry on sale at Kinokuniya in Tokyo, including Manyoshu, Japan’s oldest poetry anthology, from which the name of the new imperial era, Reiwa, is derived. Photo: Red Circle Authors Limited.However, sometimes language barriers, the economic and political importance of the country in question, its peculiar social norms and strong traditions based on a long and multi-layered history, make it preferable to spend time and efforts on deeper studies.

As for myself I have had the pleasure to be posted at the Swedish embassy in Tokyo four times after first spending three years in Kyoto, doing research on Japanese history.

This, I feel, has made it easier to understand certain perspectives of the modern political developments, but has also strengthened an urge to always look at aspects which may not always seem necessary or logical. One such aspect is Japanese poetry.

-

- Poetry is part of a nation’s intellectual DNA

A depiction of an ancient Manyoshu, Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves, recital, at Tokyo International Forum. Photo: Red Circle Authors Limited

A depiction of an ancient Manyoshu, Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves, recital, at Tokyo International Forum. Photo: Red Circle Authors LimitedIt is by no means a scientific method, only a premonition, but poetry is part of the intellectual DNA of any given country and also reflects what lies hidden under the surface.

Japanese poetry has gone through a number of phases since it first came into contact with Chinese written characters on bronze mirrors, bronze bells, wooden tablets (mokkan, 木簡) and to a certain extent paper.

After having first imitated Chinese poetry and poetic expressions, Japanese poetry began to find its own forms through the use of manyôgana (万葉がな) in the seventh and eighth centuries.

Manyôgana used certain Chinese character phonetically, while others were left as they were and used for their meanings.

To read those texts you did not only need a substantial knowledge of Chinese but also a special insight in the art of mixing meaning and pronunciation, i.e. when and where characters should be used for their meanings and when they should be used phonetically.

If one adds to that the fact that certain characters could be pronounced in various ways, it is easy to understand that writing and reading was something only a few could master.

-

- Shamanistic Songs & Symbolism

Bird symbolism, for instance, was a striking feature in early shamanism, not least in its Siberian forms, which had a strong influence on Korean shamanism and, I believe, also on Japanese shamanism.

Swedish explorers active in the late nineteenth century, found very interesting practices among the Altaic tribes. Shaman graves in certain parts of Siberia were considered holy and forbidden to touch. To protect them, poles with wooden images of birds were raised next to the graves. Korean villages also used the practice of raising high poles with wooden birds for protection at the entrance of villages.

Bird symbolism can also be found in the Nordic countries, and not just in Japan. In fact, when looking at early mythology and religious practices, there are several passages in the Kojiki (古事記) and Nihon Shoki (日本書紀), published in 712 and 720 respectively, that are almost identical with Nordic mythology.

Statue of Yamato Takeru, a legandary prince and son of the Emperor Keiko (71-130), at Ōtori Taisha. Photo: Wikipedia

Statue of Yamato Takeru, a legandary prince and son of the Emperor Keiko (71-130), at Ōtori Taisha. Photo: WikipediaFor instance, Lemminkärinen enters a wedding banquet uninvited and kills his rival, the head of the Pohja tribe. Yamato Takeru killed his rivals, the two Kumaso brothers, during a wedding feast to which he has not been invited.

Lemminkäinen is given a sword and magic armour by his mother. They were only to be used when facing danger.

Yamato Takeru receives a sword and a magic pouch from his aunt, only to be opened when in danger.

When Lemminkäinen is chased by the Pohja tribe he transforms himself into a giant bird and kills his enemies with his sword.

Yamato Takeru transforms himself into a bird after his death, in the same way as Siberian shamans were considered to have transformed themselves into birds after death.

The gate, torii, to a shrine at Chinzanso Hotel in Tokyo. Photo: Red Circle Authors

The gate, torii, to a shrine at Chinzanso Hotel in Tokyo. Photo: Red Circle AuthorsThe function of the torii is to separate the inner area of the Shinto shrine from the profane world surrounding it, much like the wooden bird on poles protected graves or villages in Siberia and Korea.

A Japanese embellon, kamon, representing Yatagarasu, the eight-span raven. Image: Wikipedia

A Japanese embellon, kamon, representing Yatagarasu, the eight-span raven. Image: WikipediaThe first Japanese Emperor Jimmu (神武), said to have ruled 660-585 B.C., was assisted by one raven, Yatagarasu (八咫烏).

These similarities do not necessarily indicate that there were early contacts between the Scandinavian and East Asian societies, only that early shamanism existed in many parts of the world and influenced early poetry and narratives.

-

- Nation-building, the Kojiki, the Record of Ancient Things, and poetry

The atmosphere in most of these poems resemble the ones you can find in the Chinese classic, Shi jing (詩経), The Book of Odes/Songs.

The following poem from the age of the first, mythical Emperor Jimmu (711 BC-585 BC), can be found in both chronicles:

Like periwinkles crawling around the great rock in the sea of Ise where the divine winds are blowing shall we crawl around them and smite them

Compare the poem with the following lines of the Shi jing:The walls of Ch’ung were powerful

he smote them, he killed them, he exterminated them, he annihilated them;

hence in the four quarters there were none

who opposed him

Cover of an illustrated English translation of the Kojiki, Japan’s oldest book. Photo: Red Circle Authors Limited

Cover of an illustrated English translation of the Kojiki, Japan’s oldest book. Photo: Red Circle Authors LimitedThe Kojiki quotes Yamato Takeru when he complains about having to engage in constant battles:

”Is it because the emperor wishes me to die soon? Why did he dispatch me to attack the evil people of the West?

Then when I came back up, why did he dispatch me once more after only a short while, without giving my troops rest, to subdue the evil people of the twelve regions of the East?”

In Shi Jing there is a similar complaint:

”What plant is not yellow; what day do we not march; what man is not going (to help in) regulating and disposing the (regions of) the four quarters?

What plant is not dark; what man is not pitiable; alas for us men of war service, we alone must be as if we were not men. We are not rhinoceroses, we are not tigers, but we go along those wilds; alas for us men of war service, morning and evening we have no leisure.”

-

- The poetry of immigration & change

Some of those immigrants might have come all the way from China, since the unification of China under the first emperor coincides relatively well with the beginning of the Yayoi period.

Gilded sword hilts from late Kofun period. Image: Wikipedia

Gilded sword hilts from late Kofun period. Image: WikipediaAnother massive wave of immigrants came with the beginning of the Kofun period (古墳時代) in the fourth century, when large tumuli began to be constructed all over western Japan.

This time, again, new techniques, armour and customs were introduced. The first poems in the Kiki kayô are probably related to this period when military campaigns must have plagued most of western Japan.

With the introduction of Buddhism in the second half of the sixth century Japan also entered in its final phase of the first unified state formation. With the end of the Asuka period (飛鳥時代 592-645) Japan can be said to have had a real state structure.

A twelve level cap and rank system was established at the court in 603 and the first 17 article constitution was adopted in 604, but it was not until, after the so-called Taika reform (大化の改新) of 645 when large land reform and new regional structures were introduced including a system for tax collection and more power being given to the central court, that there was a functioning state.

In parallel to this development important changes took place in China and on the Korean peninsula. China was again unified under the Sui dynasty in 589, only to be replaced by the Tang dynasty in 618. In 668 Korea was unified under the Shilla state.

Official delegations had been sent from Japan to China already under the Sui dynasty (589-618) and this practice continued during the Tang dynasty.

These delegations were important also for the development of poetry in Japan, since many scholars brought back knowledge about Chinese poetry. The study of Chinese poetry became a compulsory activity at the court.

-

- A new capital, seminal verse & the monumental Manyoshu

The monumental anthology, the Manyôshû (万葉集), was compiled in the latter half of the eight century and the last poems in the collection were written in 759.

The earliest poems are difficult to date and many of the poets in the twenty-volume anthology are anonymous.

Photo: Red Circle Authors Limited

Photo: Red Circle Authors LimitedThere was no common theme, but generally the poems are classified into zôka (雑歌), ”free poems”, sômon (相聞), poems about human relations and banka (挽歌), elegies.

Sometimes the anthology is classified into four periods, according to when the poems were written. The beginning of the first period is impossible to define, but it ended with the so-called Jinshin uprising (a succession battle 壬申の乱) in 671-72.

The second one ended in 710, when the capital was moved to Nara.

The third lasted between 710 and 733, when a new administrative system was introduced, and the fourth between 733 and 759.

The poems are varied in quality and content. From initially being folk songs and ballads they move to become poems of a more private character:

In Yamato

there are a number of mountains,

if you climb the well shaped

Ama no Kagu mountain

you can see smoke rising from the plains

and how the seagulls are busy over the sea.

It is a good country, Yamato.

(Emperor Jomei, 舒明, ruled 629-41)

The leaves of the bamboo grass

rustle all over the mountain

but I only think

of my wife

now that we are separated

(Kakinomoto no Hitomaro 柿本人麻呂, died sometime 708-15)

I wonder if my wife

can see my waiving sleeves

from the high Tsuno mountain

at Iwami

where I stand among the trees?

(Kakinomoto no Hitomaro)

-

- A poetic dialogue on poverty

His Hinkyû mondô no uta (貧窮問答の歌), ”A poetic dialogue about poverty”, is very explicit in its criticism of the social injustices that he could observe.

A monument for the tanka poet Yamanoue-no-Okura (660-733). Image: Wikipedia

A monument for the tanka poet Yamanoue-no-Okura (660-733). Image: WikipediaIt ends:

(…)

like a lonely pine tree by the sea

I have no padded jacket

only rags over my shoulders

I live in a ramshackle house

with scattered straw

on the dirt floor

my parents sleep at my pillow

my wife and children

down by my feet

we live in misery

from the stove

there is no smoke

and in the rice pot

there is a spider’s nest

we have even forgotten

how to cook rice,

like a pitiful bird

they raise their weak voices,

as the saying goes

what is short will be shortened

and still the voice of the

village head can be heard at the door

demanding this and that

there is nothing I can do,

is this the way of the world?

(Yamanoue no Okura)

Okura also wrote in a touching way about his dead son:He was so young and did not know the way let me pay the fee to the one who shall carry him to the Kingdom of the dead

(Yamanoue no Okura)

Manyôshû also included poets who wrote in a brighter, more humorous ways.Ôtomo no Tabito (大伴旅人 665-731), for example, wrote:

The Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove of old times longed first of all after something to drink

(Ôtomo no Tabito)

How incredibly ugly people who look for wisdom but do not drink, if you look carefully they look like monkeys

(Ôtomo no Tabito)

The most representative poet of the last Manyôshû period, and also one of the dominant Manyôshu poets was Ôtomo no Yakamochi (大伴家持 718-85), the final editor of the anthology. His 479 poems constitute almost 10 per cent of the whole collection.His poetry is very rich and varied, and it is towards the end of this huge anthology that one can speak of a poetry with several distinct Japanese characteristics, among them a kind of transient and sometimes distant, hard to define melancholy.

A thin fog hangs

over the spring field

at dusk,

in this melancholic scene

a bush warbler sings

(Ôtomo no Yakamochi)

We know that this world does not last forever, in this chilly autumn wind I can really sense that it is actually true

(Ôtomo no Yakamochi)

The poems in Manyôshû were mostly written in manyôgana. Poems written in pure Chinese, kanshi (漢詩), were also popular and can be found in parallell to the manyôgana poetry.During the Heian period (平安時代 794-1185) kanshi became dominant, and especially during the 9th century waka (和歌), ”Japanese poetry”, so dominant in the Manyôshû, had to take a step back.

Heian Period Manyoshu poetry reading display at Tokyo International Forum. Photo: Red Circle Authors Limited.

Heian Period Manyoshu poetry reading display at Tokyo International Forum. Photo: Red Circle Authors Limited.It was called the Ryôunshû (凌雲集, ”The high clouds anthology”) and was probably finished in 814.

Emperor Saga was himself among the poets selected. He also ordered the compilation of the Bunka shûreishû (文華秀麗集 ”The collection of literary beauty and honour”), which was published four years later, in 818.

A recurring question has been why Japanese poetry is so fond of the 5-7-5 and 5-7-5-5-5 metric patterns. Sometimes the explanation is that the Japanese language is especially well suited for the 5-7 rythm.

A better explanation is probably the strong influence that Chinese poetry has had from the very beginning. In Shi Jing, which was compiled sometime after the sixth century B.C., most of the poems have four character lines.

In the Chu ci (楚辭), another early Chinese anthology, attributed to the poet Qu Yuan (屈原 339-278 BC), there is a great variety and a kind of rhymed prose-poetry, the fu (賦) is commonly used.

During the Han dynasty (漢, 206 BC-220 AD) a poetry called Yuefu (樂府), so named after the bureau which collected the poetry, became popular. Yuefu was written in lines of five and seven lines. During the Tang (唐) dynasty (618-917) a distinction was made between gushi (古詩) ”older poetry” and xin ti shi (新体詩), ”new forms of poetry”.

Of the latter there was, among others, the wuyan jueju (五言絶句) with five character lines, and the qiyan jueju (七言絶句) with seven. The famous Chinese poets Li Bo (also pronounced Li Bai, 李白 701-762) and Tu Fu (or Du Fu, 杜甫 712-770) used these forms.

Towards the end of the ninth century waka poetry again became very popular, mostly due to the invention and wide spread use of the phonetic system hiragana.

In 920, the first officially ordered waka anthology, the Kokinshû (also called Kokin wakashû 古今和歌集) was completed.

-

- The Six Poetic Saints

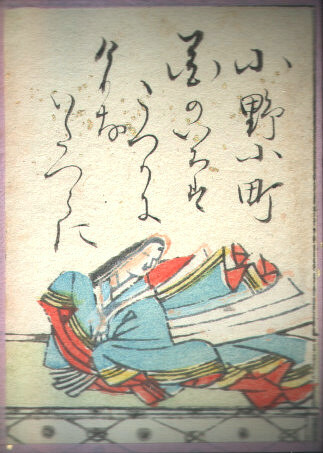

One of them was the female poet Ono no Komachi (小野小町).

She wrote many love poems and the following is quite representative:

If I cannot meet him on a moonlit night like this my thoughts keep me awake fire rages my breast and burns my heart

(Ono no Komachi)

Ono no Komachi (825-900), from the Ogura Hyakunin Isshu. Image: Wikipedia

Ono no Komachi (825-900), from the Ogura Hyakunin Isshu. Image: WikipediaLater, Japan’s most famous poet of all ages, Matsuo Bashô (松尾芭蕉 1644-94), recommended that a renga (連歌), linked poetry session should stop at 36 stanzas and be called a kasen, a phrase used still today.

One of Narihira’s poems reads:

A long time ago a man lived with his woman in a village called Fukakusa (”the thick grass”). When he had to leave her (because of work elsewhere) he read the following poem to her,

When the years have passed after I have left my village will the grass in the field perhaps grow wild again?

The woman answered,

If it is a field I shall be a quail calling for you until you return after all those years

Ki no Tsurayuki was himself a poet who belonged to the ”thirty-six poetic saints”. He was famous for writing the Tosa nikki (土佐日記), ”Tosa Diary”, the first of the Heian diaries, although attributing it to a woman, and being a prototype for the later haibun (俳文), since it mixed prose with poetry, just like haibun.A famous poem of his, published in the Kokinshû, is the following:

Noted down after having crossed the Shiga mountain and having had to bid farewell to a person I had a conversation with at a rocky spring,

Just as when you cup your hands and try to drink from the mountain spring, the person disappears like drops of water

-

- The Heian poet that inspired Basho

In his opinion mappô (末法), one of the so-called Three Ages of Buddhism, the period when buddhist teachings is no longer effective and the world again falls into chaos, began during the eleventh century.

In spite of this he became a Buddhist monk in 1140 taking the name Saigyô, which means ”the journey west” and refers to Amitâbha, the main buddha figure in Jôdô-shû the ”Pure Land” sect (浄土宗).

He travelled throughout Japan and inspired Matsuo Bashô to later make his famous journey to the interior.

Saigyô wrote a subdued, sensitive kind of poetry, using his encounters with nature as a basis for his more philosophical reflections. Some examples:

The reclining clouds are scattered by the winds at dawn, over the mountains comes the sound of the first wild geese

Now I understand,

when she swore she would

always remember,

it was a kind way of saying

she intended to forget

The small pine I saw

a long time ago in this garden

after years

it has become the stormy wind

I now hear in the tree top

However, during the Kamakura period, in spite of the political turmoil, two of Japan’s most influential poets were active, Fujiwara no Shunzei (藤原俊成 1114-1204) and his son Fujiwara no Teika (藤原定家 1162-1241).

Shunzei advocated poetry that had a kind of mystic depth, yûgen (幽玄), an expression also found in the Noh theatre.

He was also responsible for popularising the term sabi (寂), the poetically refined, in its desolate loneliness, in poetry.

An example: Written to a woman on a rainy day,

The longing is too strong, I watch the sky over the place where you are and see an opening in the haze where the spring rain falls

His son Teika left a number of works later used as instruction books for writing poetry. He became known for advocating the principle ushin (有心), ”with heart”, or poetry with elegance and style.

He was uncompromising and did not want to include poets of lesser quality in the anthologies he compiled just because they were of a high social standing.

The sleeves of the traveller

are moved by the autumn wind

in the evening sun

at the desolate

suspension bridge

During the Kamakura period renga, linked poetry, became increasingly popular, also among the ruling military class.

In the beginning humorous poems were dominant, but towards the end of the period and in the beginning of the next, the Muromachi period (室町時代 1337-1573, also called the Ashikaga period 足利時代), renga was turned into a more serious art form.

This was much due to the efforts of Nijô Yoshimoto (二条良基 1320-88), the one who in 1357 produced the first anthology of renga poetry, the Tsukubashû (菟玖波集). It consisted of twenty volumes, a common format for important anthologies. One of the volumes was dedicated to humorous renga.

The Ashikaga shoguns (1336-1573) quickly lost control of many parts of the country, one of the reasons being that they relied too much on a system of local ’constables’, shugo (守護), who gradually increased their local power.The shogunate was also weakened by fights over succession rights and the decade long Ônin war (大任の亂 1467-1477) destroyed large parts of Kyôto.

Photo: Red Circle Authors Limited.

Photo: Red Circle Authors Limited.Beautiful buildings and gardens were constructed, the Noh theatre developed into an established art form and painters like Sesshû (雪舟 1420-1506) and Kanô Masanobu (狩野正信 1434-1530) were active.

Contacts between Japan and China became frequent again, after having been broken off towards the end of the Tang dynasty.

The Chinese Ming government asked for support against Japanese pirates and these contacts led to a relatively intensive trade, where Japan mainly imported silk, porcelain, books and coins, while China imported such goods as Japanese swords, folding fans, which are said to have been invented in Japan, and copper.

Towards the end of the Muromachi period the Portuguese arrived and with them came the introduction of the musket, a weapon that had enormous consequences for Japanese history. It did not take long for the Japanese weapon smiths to make their own muskets and soon Japan became the most heavily armed country in the world.

Against this turbulent background renga reached new popularity. Two poets became especially important for its development, the priest Shinkei (心敬 1406-75) and the renga master Sôgi (宗祇 1421-1502). Shinkei is known not least for his work Sasamegoto, ”Whispers”, where he states that if one should ask any of the great poets of how waka should be written, they would probably just point at the whithering grass and the moon quietly disappearing at dawn.

During the Ônin war Shinkei, like so many other poets and artists, left Kyôto and travelled to other parts of the country. So did Sôgi, whose work Azuma mondo (吾妻問答), ”Dialogue in the Azuma region”, became important through its discussion on the concepts yûgen and ushin.

He was also one of the editors of Shinsen Tsukubashû (新撰菟玖波集), published 1495. The last volume of this work was made up of only hokku (発句), an important factor for the later development of haiku (俳句).

Sôgi was also one of three poets who compiled the hundred-stanza renga sequenze Minase sangin hyakuin (水無瀬三吟百韻), in 1488.

The first eight stanzas have been used as a model for how renga should be composed:

- 1. (Sôgi)

Snow still remains as haze covers the foot of the mountain in the evening sun

- 2. (Shôhaku 肖柏 1443-1527)

Melting water far away at the apricot-scented village

- 3. (Sôchô 宗長 1448-1532)

A wind by the river blows through the willows spring appears

- 4. (Sôgi)

The sound of a boat being poled as the day breaks

- 5. (Shôhaku)

The moon moves hidden behind the fog at night

- 6. (Sôchô)

Frost covers the fields autumn has arrived

- 7. (Sôgi)

Without thinking about the spiritual life of the insects the grass withers

- 8. (Shôhaku)

Those who walk along the fence shall see the path again

The entrance to the Nezu Museum in Tokyo. Photo: Red Circle Authors Limited

The entrance to the Nezu Museum in Tokyo. Photo: Red Circle Authors LimitedYamazaki Sôkan (山崎宗鑑 birth and death years not clear) compiled what can be described as an anti-renga anthology, the ”New Dog Tsukuba Collection” (新撰犬筑波集), around 1528-32.

Together with Arakida Moritake (荒木田守武 1473-1549) Yamazaki can be said to have created haikai no renga as a separate literary art form, although a renga variant called mushin no renga (無心の連歌), ”renga without heart”, had already developed as a reaction to all the rules that surrounded linked poetry.

Moritake is perhaps most famous for the following poem:

As if the cherry flower returned to its branch, a butterfly

It is interesting to note that humour and rule-breaking reached new heights of popularity when the country was suffering under its constant military battles. However, even the haikai no renga had its rules and the waka poet Matsunaga Teitoku (松永貞徳1571-1653) created a school called the Teimon-fû (貞門風), which tried to keep a refined and respected quality to its poetry.He more or less limited the haikai words to Chinese loanwords and frequently used so-called honkadori (本歌取り), words and phrases used in earlier classic poems.

Towards the end of the 17th century, i.e. when Japan was united under the relatively peaceful but strict Tokugawa rule (1603-1867), the Teimon-fû was challenged by the easy-going Danrin-fû (談林風), established by Nishiyama Sôin (西山宗因 1605-82). This school became especially popular in the cities. The Teimon school had its strong base in the conservative Kyôto, whereas the Danrin school was more popular in Ôsaka.

Two poems can be used to illustrate the differences between the schools:

The reason why everyone takes a nap at noon, the autumn moon

(Matsunaga Teitoku)

Watching flowers can also hurt, the neck

(Nishiyama Sôin)

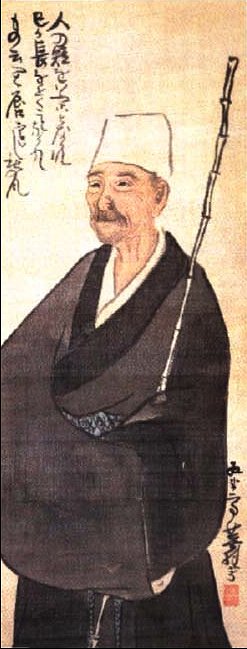

The most famous school in haikai no renga was, of course, established by Matsuo Bashô, the Shôfû (蕉風). It can be seen as a return to real poetry, while keeping both some important rules and humour. Matsuo Basho (1644-1694). Image: Wikipedia

Matsuo Basho (1644-1694). Image: Wikipedia古池や蛙飛び込む水の音

Furu ike ya, kawazu tobikomu, mizu no oto

It is a simple poem, (”The old pond, a frog jumps in, the sound of water”) but it has been translated in numerous ways:Into the calm old lake A frog with flying leap goes plop! The peaceful hush to break.

(William J. Porter)

A lonely pond in age-old stillness sleeps … A part, unstirred by sound or motion … till Suddenly into it a lithe frog leaps.

(Curtis Hidden Page)

old pond frog leaping splash

(Cid Corman)

Silent old pool Frogs jumps Kdang!

(Edward Bond)

an old pond: noises of frogs leaping in

(Hisao Kanaseki)

pond frog plop!

(James Kirkup)

Dere wasa dis frogg Gone jumpa off da logg Now he inna bogg.

(George M. Young Jr.)

A frog statue at a shrine in Azubu-Juban in Tokyo. The word frog, kaeru in Japanese, with some pronunciations sounds identical to the phrase return, and thus frogs are considered lucky charms or capable of providing a blessing which will lead to money spent returning. Photo: Red Circle Authors Limited.

A frog statue at a shrine in Azubu-Juban in Tokyo. The word frog, kaeru in Japanese, with some pronunciations sounds identical to the phrase return, and thus frogs are considered lucky charms or capable of providing a blessing which will lead to money spent returning. Photo: Red Circle Authors Limited.The yellow rosebush (yamabuki 山吹) a frog jumps the sound of water

The frog poem was actually a hokku followed by a wakiku (脇句) composed by Takarai Kikaku (宝井其角 1661-1707):Over the young reeds hangs a spider’s web

The pond in a garden near Waseda University in Tokyo which allegedly inspired Basho’s famous haiku “The Old Pond.” Photo: Red Circle Authors Limited

The pond in a garden near Waseda University in Tokyo which allegedly inspired Basho’s famous haiku “The Old Pond.” Photo: Red Circle Authors LimitedDuring his life time Bashô was a well-known poet and teacher, but he was not alone.

There were many others, and after his death his name was momentarily lost in obscurity, until another very famous poet, Yosa Buson (与謝蕪村 1716-83) became instrumental in the Bashô revival movement.

Looking out from a memorial building on Munatsuki Hill near Waseda University onto a garden where the poet Basho once resided that is said to contain the pond where he wrote his famous poem, “The Pond”. Photo: Red Circle Authors Limited.

Looking out from a memorial building on Munatsuki Hill near Waseda University onto a garden where the poet Basho once resided that is said to contain the pond where he wrote his famous poem, “The Pond”. Photo: Red Circle Authors Limited.Bashô, Buson and Kobayashi Issa (小林一茶 1763-1828) are well-known all over the world as haiku poets, but they were probably more engaged in renga poetry, and many of their most famous poems were hokku, the starting verse in a renga sequence, or poems inserted into haibun.

Undeniably, they also wrote plenty of independent hokku. The Meiji restoration 1868 opened up Japan in many ways, also on the literary scene. European romantic and symbolist poets were discovered and translated into Japanese.

In 1871 an Imperial Poetry Bureau was established and one of its objectives was to save classical poetry from disappearing in the wave of the new influences that came. It viewed the poetry of Kokinshû as the model to follow. But rather than saving tanka from extinction, the Bureau helped inspire Shiki and others to advocate a true tanka reform.

Pioneers were poets like Ochiai Naobumi (落合直文 1861-1935) and Yosano Tekkan (与謝野鉄幹1873-1935), even if Shiki got a lot of credit for both reforming tanka and starting the haiku movement.

-

- A nation’s welfare depends on its literary expressions

He was married to Yosano Akiko (与謝野晶子 1878-1942), who surpassed him as a tanka poet and became one of the most important female literary figures of Japan.

Yosano Akiko (1878-1942), poet, feminist and social reformer. Image: Wikipedia

Yosano Akiko (1878-1942), poet, feminist and social reformer. Image: WikipediaFor instance,

Spring is short and everything is perishable in this life, I said and let him grip my vigorous breasts

She also expressed herself in other shocking ways:The sound of life’s ending is determined by God, in my world you can listen to the sound of the ax against the koto

Another prominent tanka poet was Saitô Mokichi (斎藤茂吉 1882-1953). He wrote most his poems in sequences called rensaku (連作), which differed from renga in that the poems followed the same theme. In renga the poem keeps moving towards new themes.When his teacher Itô Sachio (伊藤左千夫 1864-1913) passed away he wrote:

I run as fast as I can my road is dark it is heavy hard to endure my road is dark

The faint light that has spread from my own firefly has been killed my road is dark

When someone dies she does not exist, I sigh and take pills in order to sleep

Perhaps I wake up in Shinano where the poppies spread their light on the other side of the lake

Mokichi was one of several poets who was strongly influenced by the political climate in the thirties and the forties. He even wrote, in an appreciating way, about Hitler and the Nazis.During a trip in Germany he wrote:

A company of soldiers with the red swastika flags raised high walks along the river bank

You can hear the marching songs Hitler’s speech has perhaps just ended

After the war he was very remorseful and began to write more poems about nature, as if wishing to wash himself from feelings of guilt.I have come to the Mogami river on the river bed you can hear the sound of wings of the crows

After the end of the Second World War quite a few returning soldiers established themselves as poets, often reflecting on their war experiences.Ishihara Yoshirô (石原吉郎 1919–1977), who spent eight years in a prison camp in Siberia after the war, wrote a poem called ”The funeral procession”:

No one remembers

the name of the station where

we started our journey

only that on the right side

it was always noon

and to the left

always midnight,

the train passed through

a majestic landscape

(…)

but the smell of death was everywhere,

I was also there,

half of us were already dead souls

we leaned against each other,

connected,

sure, we had a little bit to eat and drink

but for some

it was just an open canal

for everything to pass through

and yes, I was also there

leaning against the window

full of reproach,

now and then I chewed

on a rotten apple,

I and my dead soul

took turns

in disappearing towards an unknown future,

we waited for the train to reach

its destination

and wondered who was actually at the engine,

when we passed a large iron bridge

the railings sang,

many dead souls

tried to lean against their hungry palms,

I am trying to remember the name

of the station where we began our journey

(…)

Death was everywhere,

when we drank our water,

waited for the playing-cards,

put on our shirts with dirty collars,

raised our raw laughters, death was not an unusual guest,

the most natural thing in the world,

like an old friend

(…)

as individuals who had lost the battle

we also reproached each other,

drunkards and swindlers

farmers and locksmiths

hypocrites and bank clerks

comforted each other and argued

We were to be sent back to our homeland

when we arrived on our ship

we were all scattered,

each to his own destiny

(…)

It was natural that the war itself and the end of the war should have an influence on the post-war poets, but once they had somehow cleared their minds, many of them moved towards more avant-garde and surrealistic poetry.

In his ’Bluegreen icicle’, 「青氷柱」, 1995, he wrote:

The green frog of the moonlight does not let itself grow older

Oppressive heat, the dream in the shadow of the big fountain

The flowers separate themselves from their shadows the mountain is full of flowers

The eyes of the ant on the reverberating plate under the summer clouds

The young horse gallops to freedom from the dream, a liberated moon

I place the shoes pointing this way so they point that way towards the burial-ground

Unsurpassed, it lies there upside-down after being shot dead, the wild duck

The female poet Ishigaki Rin (石垣りん, 1920-2004) had some resemblance with Yosano Akiko, especially in her rebellious attitude, but was perhaps more cynical:In the stomachs of one hundred guests

On the table one hundred plates

in front of one hundred guests

on the plates one hundred flatfish

the subtle sound of cutlery

of the fish some bones are left

a bit of the head, and the tail

(What would Her Highness say if she saw you leave too much?)

One hundred gentlemen, and ladies wipe their mouths with white napkins and speak with dignity to each other “What is it with this world?”

In one hundred stomachs lie one hundred dead fish

To describe the poetry of today’s Japan is almost too challenging a task, and this will be avoided here. Suffice to say that it is extremely rich.Unfortunately, in that richness one can find a rigid division between the various expressions of poetry. A haijin, a poet writing haiku, is not supposed to write modern poetry, and a modern poet is not supposed to write tanka.

Very few write both haiku and tanka. Some poets lament this, but few move across these borders.

A model at Tokyo International Forum depicting aristocratic Japanese women looking out at a Heian Court proceedings. Photograph: Red Circle Authors

A model at Tokyo International Forum depicting aristocratic Japanese women looking out at a Heian Court proceedings. Photograph: Red Circle Authors