Tokyo Station lit up at night, taken from the Marunouchi Oazo side Photo: Toshinori Baba (Wikimedia)

Tokyo Station lit up at night, taken from the Marunouchi Oazo side Photo: Toshinori Baba (Wikimedia)D

uring most weekdays more people pass through Tokyo’s busiest station than live in Paris. The figures are staggering. Of the 50 busiest stations in the world, 26 are located in Tokyo, and 45 in Japan. But it isn’t just the Guinness Book of Records that loves writing about Japan’s stations and rail network. Japanese trains and stations feature in many of the 70,000 new books published in Japan every year, as well as in thousands of newspaper articles and online posts.

Most journeys in Japan involve reading and writing. More than 80% of people commute to work by train and commuting time, according to a survey by the NHK Culture Research Institute, is now on average 1 hour 19 minutes per day, and rising.

Stations and trains, the backbone of modern Japan, are also brilliant narrative devices. Shinjuku station, the world’s busiest used by 3.5 million people every day, is actually a city-like hub collective of five different interconnected stations, with 51 platforms and 12 lines running through it.

This Tokyo station has almost as many exits as London Underground (Europe’s largest) has stations. Shinjuku is not just linked physically through subterranean walkways to famous bookshops like Kinokuniya, but like other important Tokyo stations (including Tokyo, Ueno and Ikebukuro) it is linked to books written by some of Japan’s most famous and interesting authors.

-

- All Aboard the Japanese Literary Express

N

ine years after London Underground started operating the world’s first underground train service, the Tokyo-Yokohama line, Japan’s first rail service, opened for service in 1872. Reportedly, some of the first passengers took off their shoes and left them on the platform before boarding the first trains. The cultural changes that trains brought about were enormous.  Poster for a special exhibition at the Omiya Railway Museum commemorating the 150th anniversary of the start of the Meiji era (1868-1912) and the so-called dawn of railroads in Japan. Image: JapanForward

Poster for a special exhibition at the Omiya Railway Museum commemorating the 150th anniversary of the start of the Meiji era (1868-1912) and the so-called dawn of railroads in Japan. Image: JapanForwardJapan was finally opening up to the world after hundreds of years of self-imposed isolation. Trains, however, may have had a bigger impact on Japanese society than anything else at this time.

Aside from new influences from foreign literature arriving in translation, Japanese authors responded to the arrival of this new mode of travel and the new professions and jobs that it threw up in its wake.

Train services and urbanisation played a critical part in Japan’s rapid modernisation programme. So much so that the nation has been firmly committed to rail transport ever since.

The subject of travel had already established itself as a popular literary genre before the arrival of the railways. Shank’s Mare, for instance, is a comic novel written by Jippensha Ikku (1765-1831), that follows two amiable scoundrels on a madcap road trip adventure along the great highway leading from Edo (present-day Tokyo) to Kyoto (Tokaido).

Naturally, rail transport made travel much more accessible and commonplace and created a host of new locations for authors to write about or use for chance encounters.

These books, as well as the quality and extent of Japan’s rail network, have helped imprint stations and trains on the Japanese national psyche.

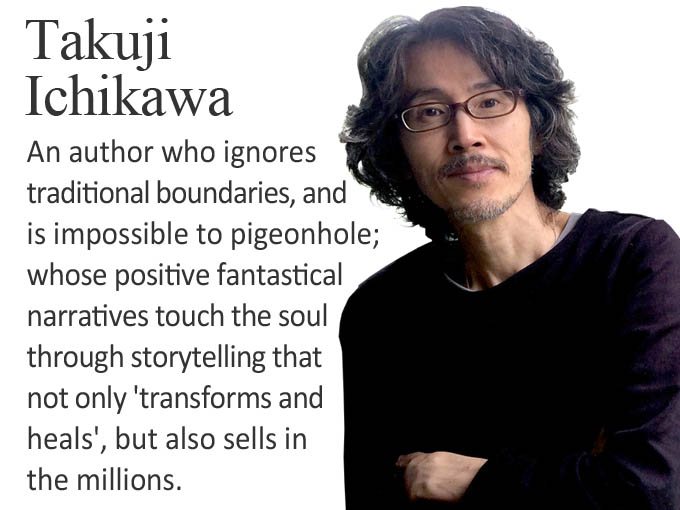

Cover of English translation of the Kenji Miyazawa nine-chapter novel, Night on the Milk Way Train, which was originally published posthumously in 1934.

Cover of English translation of the Kenji Miyazawa nine-chapter novel, Night on the Milk Way Train, which was originally published posthumously in 1934.This is probably one of Japan’s favourite children’s books, and was written by a man who also wrote a very popular and well-known poem, “Strong in the Rain”, which has a similar iconic resonance as Rudyard Kipling’s (1865-1936) poem If.

Both the book and the poem have worked their way into Japan’s cultural zeitgeist.

Night On the Milky Way Train is a much-loved classic, studied and read by children at schools across Japan. The book published has been adapted for anime and the stage. Miyazawa wrote the book after the death of his little sister Toshi in 1922 – the year before a major earthquake hit Tokyo killing more than one hundred thousand people.

The book, which Miyazaki spent seven years writing, was published after his death, and deals with such universal themes as the challenges of growing up, friendship, bereavement and loss. It is a magical story about a young boy, Giovanni, with a special green ticket that allows him to travel on a train through the heavens, getting on and off at various fantastic locations with his only friend Campanella.

Giovanni meets other young children on his adventure who, sadly, like Campanella, are on route to the next world. Giovanni, however, is in a privileged position with his special green ticket, which allows him to return home with newly found purpose and a new attitude for living a fulfilling and happy life.

It is a story that has captivated countless readers. And many have translated it including Roger Pulvers, whose serialisation in 1983 in The Mainichi Daily News was the very first in English. This book in particular has delighted each generation growing up and continues to provide essential comfort to anyone when dealing with personal tragedy. It has also contributed to Japan’s national obsession with trains, stations, and the romance of train-travel itself.

-

- Urbanisation and Mobilisation

T

rains proved to be the great game-changer in Japan, creating far reaching ‘networks of modernity’ that affected people from different classes, regions and professions. Many cities, especially Tokyo, changed, physically, culturally and socially following the arrival of the trains.

Nishi Oyama Station, Kagoshima, Japan. Image: Wikimedia.

Nishi Oyama Station, Kagoshima, Japan. Image: Wikimedia.By the same token, it became harder for local elites to remain local and elite.

Literacy rates rose, fresh narratives were penned and a new generation of authors and readers who lived modern urban lives emerged.

One such author was Natsume Soseki (1867-1916) whose work appeared in print in the early 1900s. Many of his books include descriptions of long-distance train journeys and urban stations, as well as odd but interesting encounters with people from different walks of life.

Soseki’s novel Botchan, published in 1906, beautifully illustrates the impact that trains and increased mobility had on Japanese society.

In this story that’s still popular to this day, a Tokyo-raised and spoilt young man named Botchan arrives in Matsuyama in Shikoku, the smallest of Japan’s four main Islands, as a teacher.

Like many inexperienced teachers arriving from afar, with their own views and values of how things should be, he clashes with both staff and students. And he gives the locals slightly ridiculous but entertaining nicknames like Red Shirt, Squash, Madonna and Porcupine, and tries to fight the local system. While his antics and endeavours leave their mark, he only stays a couple of months before returning to Tokyo to get on with his life – having given the reader a very entertaining detour.

Unlike Matsuyama, Tokyo was the place to be in the 1920s. The population of urban Tokyo increased by 30% reaching 9.9 million in 1930 and then went on to increase by a further 28% in the next decade.

Model of original Manseibashi Station, Kanda Tokyo, closed in 1943. Opened in 1912 and subsequently an underground station in 1930. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.

Model of original Manseibashi Station, Kanda Tokyo, closed in 1943. Opened in 1912 and subsequently an underground station in 1930. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.Here writers would discover and write about delinquents and marginalized youth. Indeed, many still write about these youngsters at the margins of society today.

Junichiro Tanizaki (1886-1965), for example, wrote about suburban Tokyo at night in his novels, such as Naomi (Chijin no ai); as did Yasunari Kawabata (1899-1972), who went on to win the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1968.

Other notable authors from this period of burgeoning railways include Shusei Tokuda (1871-1943) and Toson Shimazaki (1872-1943) as well as the tanka poet Takuboku Ishikawa (1886-1912) who penned many poems about trains and stations. “At the Station”, translated by Roger Pulvers, is a good example of one of these: I slip into the crowd/Just to hear the accent/of my faraway home town.

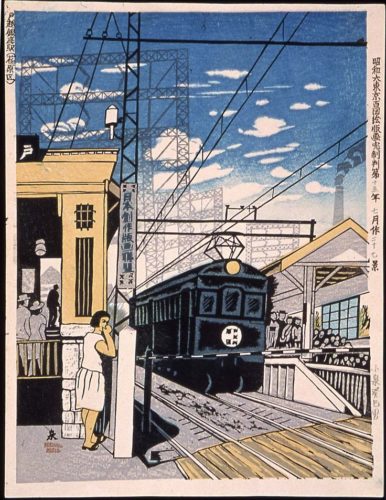

Ginza Station, July 1940, by Kishio Koizumi (1893-1945). Imagine; Wikimedia.

Ginza Station, July 1940, by Kishio Koizumi (1893-1945). Imagine; Wikimedia.Of course, urbanisation impacted on places within easy reach from the capital.

The Dancing Girl of Izu (Izu no odoriko), also by Kawabata and published in 1926, demonstrates this rather well. It is a novella about a Tokyo student who travels by train from Tokyo to the Izu Peninsula where he meets a troupe of dancers and encounters one young dancer that takes his fancy.

Its depiction of young love is so well known in Japan that for well over 30 years a train that runs from both Tokyo and Ikebukuro to Izu has carried the name Odoriko, The Dancer.

Other train operators with conveniently located scenic tourist spots on their routes, perfect for short stays of one night or more, have followed suit by dreaming up similar names for their trains. RomanceCar being one of them.

Memorial at location in Nagasaki of Japan’s first railroad. The track was laid by Thomas B. Glover (1836-1911), a Scottish merchant and entrepreneur, in 1865 from the point where this memorial stone is located towards the Matsugae Bridge. Japan’s first steam train dubbed the Iron Duke was demonstrated using this track. Despite it never actually being used for commercial or passenger services it is considered a critical milestone in Japan’s modernisation. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.

Memorial at location in Nagasaki of Japan’s first railroad. The track was laid by Thomas B. Glover (1836-1911), a Scottish merchant and entrepreneur, in 1865 from the point where this memorial stone is located towards the Matsugae Bridge. Japan’s first steam train dubbed the Iron Duke was demonstrated using this track. Despite it never actually being used for commercial or passenger services it is considered a critical milestone in Japan’s modernisation. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.As the novelty of trains dissipated and rail transport become part of the regular fabric of modern Japanese society, their employment as plot devices also evolved, often in very interesting and creative ways, never disappearing completely, but by becoming part of the fabric of the novel, and not the main focus of the story. Perhaps with the exception of some detective fiction and murder mysteries.

-

- Station-to-Station

A

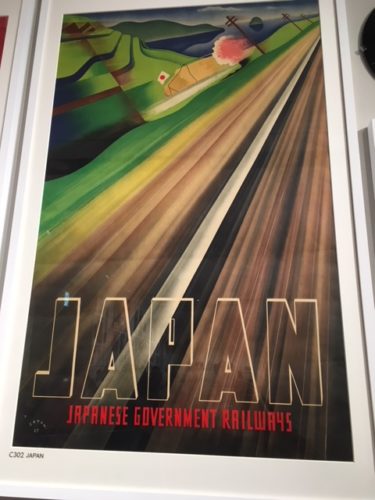

n excellent contemporary example is Haruki Murakami’s short story The Town of Cats, published in English translation in The New Yorker in 2011. Train travel plays an important narrative role in this thought-provoking story on multiple levels. The story starts and ends with a station: Koenji and Chikura.  Promotional poster on display at the Ad Museum Tokyo. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.

Promotional poster on display at the Ad Museum Tokyo. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.The trip to see his father is one that Tengo is not looking forward to, but feels compelled to make.

On the train Tengo reads a book, by a German author, about another young man who is also on a train journey.

But unlike Tengo, this young man has no particular destination in mind, and oddly finds himself in a town that has been vacated and is now occupied by cats.

He eventually reads part of this fantastical novel to his father and despite hardly speaking to each other it helps them reach some kind of understanding. It is a touching story, beautifully crafted, with travel, trains and stations subtly embedded into its narrative. A tale of emotional voids being filled consciously or through simple momentum, as well as entropy and ageing.

Stations and railway journeys do not just provide a vehicle to frame a story. Many contemporary authors have followed in Kawabata’s footsteps and used large city-like stations or areas around them as settings. Many have also taken a similar path and focused on sub-cultures, for which some railway stations are famous.

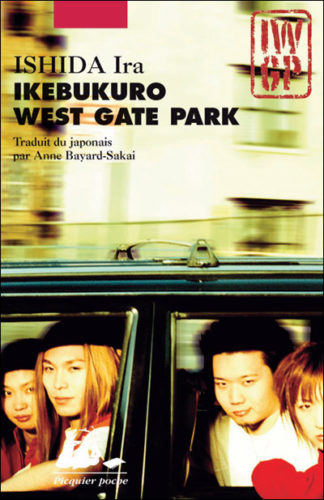

Cover of French translation edition of Ira Ishida’s Ikebukuro West Gate Park (IWGP).

Cover of French translation edition of Ira Ishida’s Ikebukuro West Gate Park (IWGP).IWGP is about marginalized youth, and the adventures of 20-year-old Makoto, his friends and a local gang leader, all of whom hang out at the park near Ikebukuro Station, Tokyo’s third busiest. It is an area with an edgy reputation, girly bars and a small Chinatown.

The prize-winning IWPG was Ishida’s debut work. Not only did it establish him as a writer, but it went on to become a popular manga and television series with Makoto playing an urban crime-solving youth.

Another excellent example can be found in the writing of the Akutagawa-winning author, Miri Yu. Her 2014 novel JR Ueno Park Entrance now probably falls within Japan’s corpus of so-called Olympic Literature, and uses the Olympics and the station for social commentary.

It tells the tale of Kazu, a man who moves to Tokyo from Fukushima to support his family at the time of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics.

Thirty-seven years after his Olympic-timed arrival at Japan’s busiest station, Kazu finds himself back there once again.

This time living in a homeless camp in a park near the station’s entrance ‘used and discarded’ a decade after Japanese economic bubble collapsed. His story mirrors the arc, the missed opportunities, and the lows that the failing economy had brought about.

At the other end of the spectrum, Mikie Ando’s Yumemino Station Lost and Found is a young adult novel that exudes hope and inspiration. This tale revolves around a lonely young girl who feels lost, having changed schools, and finds herself in a station’s lost and found office where the attendant starts reading her stories that have been found in a notebook. She returns daily to listen to a different tale each time until she decides to set off on her own journey, to find her own purpose, and to create her own narrative.

Stations in Japan are part of the daily fabric of the lives of many, reflecting their own particular circumstances. And despite some stations being shared daily by millions of people of all ages, including those famously packed commuter trains, the experience of passing through them can still often be unique, isolating and at times lonely.

Life’s rich tapestry can be found in the world of railways. Stations can be magical nodes, life-affirming and life-transforming places. Places where unusual sub-cultures and economies take root. They can also provide detours, or in the worst scenarios, be miserable dead ends.

-

- Trainspotting and timetables

T

he rail network itself, as well as the individuals that use it, can also provide a fascinating narrative. And for some it is something of a fanatical obsession. ‘Just as Japan’s trains are in a league of their own’, writes The Washington Post, ‘so too are its trainspotters’. For a mountainous island nation plagued by earthquakes, Japan’s railway network is remarkably large with slightly less than 30 thousand kilometers of track, which is 60% of the size of Germany’s network in terms of track.

Yet more than three times the number of passengers travel on Japan’s network each year. That’s an amazing 3 billion trips – triple the number of books distributed each year in Japan.

The bullet train, shinkansen, passing Mount Fuji. Image: Wikipedia.

The bullet train, shinkansen, passing Mount Fuji. Image: Wikipedia.The Bullet Train now comes in many different models with different speeds and designs, including a special Hello Kitty pink model on the Osaka-Fukuoka route.

It is probably much harder to spot someone who hates trains in Japan than it is to find a train-spotter. In fact, the train-spotters, like the trains themselves, have been classified into different types with their own monikers like eki-tetsu (station geeks) and sharyo-tetsu (train-design geeks) to name just a couple.

Closed spaces, punctual trains and complex timetables are dream ingredients for authors of so-called Locked Room detective fiction, in which murders are committed in seemly impossible to fathom circumstances. The genre has been very successfully revived in Japan by writers like Soji Shimada, of The Tokyo Zodiac Murders fame.

-

- Murders on the Oriental Kyuko (Express)

L

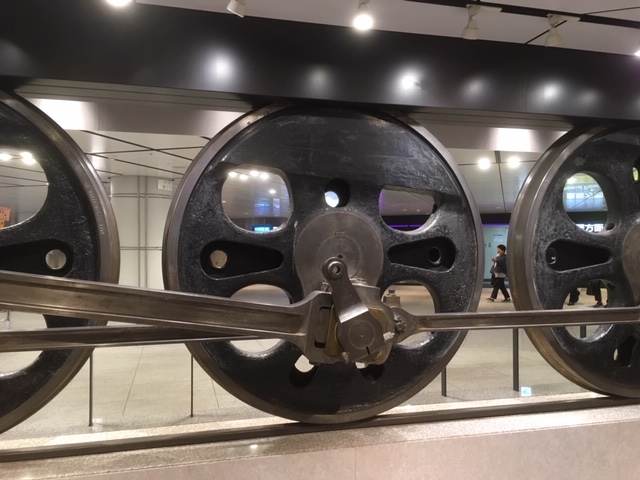

et’s not forget that tragedy can also befall the railways. Two Japanese prime ministers have been assassinated at Tokyo Station: Takashi Hara (1856-1921) and Osachi Hamaguchi (1870-1931).  Locomotive wheel installation at Tokyo Station: Photograph Red Circle Authors Limited

Locomotive wheel installation at Tokyo Station: Photograph Red Circle Authors LimitedFascinating books have been written about this tragic event by Randy Taguchi: A Man Hung Upside Down, and Haruki Murakami: Underground.

Image of Teke Teke. Source: Wikipedia.

Image of Teke Teke. Source: Wikipedia.In the 1965 James Bond film You Only Live Twice, 007 comes to Japan, and the head of the Japanese secret service Tanaka travels on a private underground train from his own secure and secret platform, which helped fuel rumours over this secret network.

Another urban legend is known as Teke Teke and concerns a woman or schoolgirl who fell on a train line and was cut in half, and who at night makes a Teke Teke noise as she pulls herself along by her elbows.

DVD cover of the Japanese adaption of Agatha Christie’s famous whodunit Murder on the Orient Express.

DVD cover of the Japanese adaption of Agatha Christie’s famous whodunit Murder on the Orient Express.The book and film have been very popular in Japan; to the extent that there is now even an Agatha Christie Award for unpublished Japanese authors. In 2015 the book was adapted for a two-part television special, with a stellar Japanese cast, part one faithful to the original but set in Japan in 1933 and part two with a new original story.

Interestingly, Ogai Mori (1862-1922) who wrote Japan’s first modern short story, The Dancing Girl (Maihime) in 1890, after studying in Germany, is reportedly the first Japanese person known to have actually travelled on the Orient Express, which began operating in 1833.

Train timetables have also featured in Japanese mysteries as alibis that are hard to refute. Something that few other countries whose trains are much less reliable could ever pull-off.

The first Japanese railway murder mystery novel that used the timetable as an alibi is said to have been The Tragedy of the Funatomi (Funatomi no sangeki) by Yu Aoi (1909-1975) published in 1936, two years after the publication of Christie’s novel. The book is about the murder of a mother and daughter from Osaka.

Toy train modelled on the Orient Express on sale at a Tokyo shop. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.

Toy train modelled on the Orient Express on sale at a Tokyo shop. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.These cemented his reputation as an author of whodunits and travel-related mysteries. He has gone on to write more than 550 novels, which have sold around 200 million copies in print.

According to the Guinness Book of Records, Christie, who holds the world record, has sold a staggering 2 billion copies. Nishimura’s fictional detective Totsugawa is one of Japan’s most popular; and a two-hour mystery show broadcast on national television, based on his books, is the longest running series of its kind in Japan.

That said, Points and Lines (Ten to Sen) by Seicho Matsumoto (1909-1992), published in 1958, is sometimes cited as one of the best Japanese railway mysteries ever written.

It is a classic whodunnit set in postwar Japan, which makes interesting reading in itself. Points and Lines also relies on timetables, and maps to break a cast-iron alibi and solve a double-murder that looks like a double-suicide of two lovers.

It is quite literally a tale told from the tracks as it was written in a room at Tokyo Station Hotel. It has inspired countless fans, and is the favourite of many, including the American author James Kendley, who writes horror stories set in Japan.

Many Japanese authors, such as Soji Shimada have carried on this tradition brilliantly. Shimada, who has earned the moniker as Japan’s God of Mystery, for example, has penned several books featuring trains and murders that have been successfully adapted for television in Japan. A recent and interesting upshot of all this train mystery activity is a mini-boom in the launch of new luxury sleeper trains. Needless to say, these trains, which look like super-luxury boutique hotels on wheels, are crime free. Some have impressive names such as Twilight Express, Seven Stars and Shiki-Shima. And they all boast murderously expensive ticket prices.

-

- A digital hoax or true love?

R

egrettably, train whodunits aren’t as popular or common as they once were. But Train Man (Densha Otoko) by Hitori Nakano is a recent novel that has certainly given the genre a shot in the arm and demonstrated that trains and train travel still provide a compelling narrative – one that hasn’t run out of steam and probably never will. The book is an unfolding love story involving a young man, a geek with limited social skills who can’t talk to girls. He manages to inadvertently change the course of his life by stopping a drunk man from harassing a young woman (known as Miss Hermes) on a train.

She thanks him and asks for his address, and a relationship begins to blossom, a relationship that our protagonist shares online with his followers up until the point that a sexual encounter is likely to occur.

The story takes the form of a stream of digital posts over the period of 57 days and has a very authentic feel, though whether or not this is a true story isn’t at all clear. Nevertheless, the book published in 2004 has lead to a number of spin-offs including a film, a television drama and manga, not to mention a flurry of similarly themed books.

-

- Tales from the network: To be continued…

Y

esterday’s revolution in railway networks has today been superseded by digital networks. Gone are the days of reading newspapers and manga in print. Tablets and mobiles are now ubiquitous. But interestingly, you still do see people reading print format books. One way or another, reading continues unabated. According the Research Institute for Publications, sales of digital manga in Japan surpassed print editions for the first time in 2017. Digital manga sales rose 17% on the previous year, while sales of physical print format manga fell by roughly 14%. A new point on the line towards media digitisation had, it seemed, been reached.

Reading habits have in fact been changing over the last decade. Initially, it was cell phones and now it is the next generation smartphones that have led the charge. The world’s first cell phone novel, or keitai shosetsu, Deep Love, was released in 2003. Written by a 30-year-old Japanese man, it’s a gritty young-adult novel about a girl who turns to prostitution to pay for her boyfriend’s heart surgery, and dies herself after contracting AIDS. Like Train Man, it was published in print, manga and made into a movie after finding initial success on the small screens of mostly young women commuting to work.

In traditional book format it sold more than 2.5 million copies.

Keitai shosetsu are sent out by text-message or email as part of a subscription in small chapter instalments, each consisting of about 70-100 words.

Japan has a long and rich history of fiction in short-form and serialisation, making it the perfect environment for this.

Reading a confessional slightly over-the-top love story on a tiny mobile phone screen on a packed commuter train provides many with an entertaining few moments of escape on their way to or from work. In 2007, half of the top ten best selling fiction titles in Japan originated as ketai shosetsu, but this publishing boom is now over.

Nonetheless, billions of train journeys still take place and almost all passengers carry reading devices of some form. Narratives from off and on the tracks are destined to continue and start new publishing trends, both local and international. Stations, trains and tracks have provided a versatile and rich vein for Japan’s creative writers, and have managed to convey so many facets of Japanese society along the way.

As David Bowie sang in the title track of his 1976 album Station to Station: ‘Here are we, one magical moment. Such is the stuff, from where dreams are woven. Bending sound, dredging the ocean. Lost in my circle. Here am I, flashing no colour, Tall in this room overlooking the ocean. Here are we, one magical moment’.

Novels, like stations and trains, take people to places they’ve never been before. Some may well have magical moments and mystery about them. But what matters most, however, is getting onboard and in the case of books, turning to or clicking on the first page.

© Red Circle Authors Limited

Aizu Railway's Yunokami-Onsen Station in Fukushima Prefecture. The station has a footbath onsen, hot spring, and a sunken fireplace making it popular amongst railway enthusiasts. Image: Wikipedia.

Aizu Railway's Yunokami-Onsen Station in Fukushima Prefecture. The station has a footbath onsen, hot spring, and a sunken fireplace making it popular amongst railway enthusiasts. Image: Wikipedia.