Photo: Red Circle Authors

Photo: Red Circle AuthorsT

he Uncanny Valley isn’t a work of fiction or science fiction or an article about how curious, weird and unknowable Japan is. Neither is it an odd tourist destination in Japan. It is, in fact, a 1970 scientific hypothesis about robots put forward by Masahiro Mori, one of Japan’s best-known engineers working in the field. The theory can be applied to imagined literary robots, Japanese bunkaru puppets, and even monsters like zombies and Frankenstein.

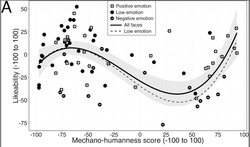

Mori’s theory, presented when he was a professor at Tokyo Institute of Technology, Bukimi no tani (不気味の谷), is that there comes a point where a robot’s human-like attributes become less appealing to humans.

Human-like traits displayed by robots can be endearing and socially acceptable up to a point. But once a robot becomes uncannily human-like, it is likely to elicit feelings of revulsion in us.

Diagram of the Uncanny Valley with Likeability plotted against Mechano-humanness. Image: Wikipedia.

Diagram of the Uncanny Valley with Likeability plotted against Mechano-humanness. Image: Wikipedia.The sudden repulsive response to some humanoid robots is The Uncanny Valley. The Uncanny Valley is where robot designers dread their robots will end up.

This is something that robot engineers may have only figured out and formalised in a scientific hypothesis in the 1970s, but Western authors have had an inkling that this may have been the case for at least two hundred years, since Mary Shelley (1797-1851) published her novella about Frankenstein in 1818. Arguably, in Japan the repulsive response has been known for longer.

The designers of the 17th-century mechanical Japanese toys (karakuri Ningyo) would have instinctively known this. These karakuri ningyo mark the starting point of Japan’s long march towards becoming the Robot Nation it is today.

They were designed to resemble Noh actors – traditional Japanese entertainers who still perform their ancient form of musical-drama to this day. Noh actors wear masks, beautiful kimonos, and express themselves through intricate and subtle movements.

Scientists have found in studies of the brain, using MRI brain scanning, that ‘perceptual mismatch’ between ‘appearance and motion’ in very human-like androids cause considerable unease. It is these behavioral mismatches between how things move and look that Noh actors and karakuri ningyo designers have exploited so cleverly for hundreds of years.

The uncanny valley has come to occupy an important place in the study of human-robot interactions. And it is now even possible to plot on a chart degrees of empathy and aversion to human-likeness (shinwakan), and compare the human emotional response to various types of robots ranging from industrial robots to their eerily lifelike counterparts.

In the US Boston Dynamics has been developing military robots that are more animal-like than human, and these have been met with a nervous foreboding from the general public.

Japan, of course, is better known for its cute social robots that are widely publicised, and its industrial robots, some of which are decorated with smiles and are not often on public display.

Some researchers are also using this approach to better understand our reactions to individuals with facial disfigurements and other areas of behavioural research.

The best literary authors have been describing imagined creatures that sometimes mirror us or at times are slightly physically or emotionally out of kilter depending on the emotional responses their narratives are designed to elicit from their readers: a mechanical-monster; or a fully socialised or anti-social companion robot; or a narrative about parental rejection, for example.

Thankfully, literary critics and publishers, however, are not yet using the curve to dream up new sub-genres of robot or monster literature designed to be both page-turning and addictively terrifying.

Famed for its ‘robot-embrace’ and love of all things technological, Japan certainly doesn’t show the slightest hints of robophobia. Nevertheless, there isn’t yet a theme park in Japan where you can hug and play with uncanny or adorable robots – depending on your preferences.

Honda’s ASIMO Robot in action at The National Museum of Emerging Science and Innovation, Miraikan, in Tokyo. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.

Honda’s ASIMO Robot in action at The National Museum of Emerging Science and Innovation, Miraikan, in Tokyo. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited.Japan’s robot engineers may be world-class, but so too are Japan’s robot-obsessed authors who, like the nation’s industrial robots, have been beavering away unseen for years. Japan’s best creative writers have been writing robot narratives ever since the word robot arrived in Japan in 1924, and some even before this.

There is a long Japanese tradition of writing about robots or artificial humans, jinzo ningen. Sanjugo Naoki (1891-1934), who the prestigious Naoki Literary Prize is named after, wrote several, including his famous short story, The Robot and the Weight of The Bed.

It is set in the future when Japan has electrically controlled cars (not dissimilar to the electric and autonomous vehicles being developed today) designed to automatically avoid accidents.

A contemporary and revered author who has used robots as a plot-device and rarely writes about anything that would normally be classified as science fiction, is Kazufumi Shiraishi, who followed in his father’s footsteps and won the Naoki Prize in 2010. Shiraishi’s short story Stand-in Companion is a touching story about finding meaning and balance in a society in which advanced technology and major demographic problems are very evident.

Another notable contemporary example is One Love Chigusa by Soji Shimada, the so-called Japanese master of the post-modern whodunnit, who is a household name in Japan.

Shimada’s novella, an unusual type of narrative for him, is a love story and an homage to Osamu Tezuka (1928-1989), who himself had an immense impact on Japanese robot-related storytelling as well as animation, is set in a future Beijing.

Japan’s robot tales are many and varied. In fact, it’s no exaggeration to say that many of Japan’s best-known authors have at some time written short stories or books about robots.

A common narrative theme that seems to appear in many of them is one that features unusual ‘companion-robots’. These stories tend to say more about the state of society and human relationships than Japanese attitudes towards technology and automata per se.

However, it’s not a genre that’s confined to the writers of science fiction, manga and anime. Delve into this world and you’ll discover everything from cyberpunks, post-humans, cyborgs and blue robot cats to nuclear powered robots, aquatic-humans, and hybrid sex and housekeeping robots.

An incredible literary ‘theme park’ featuring extraordinary robots exists. And the price of a book is always going to be much more affordable than a ticket to one of Japan’s many theme parks or a meal at a trendy Tokyo robot restaurant.

-

- Post-war robot literature reflects a rapidly changing Japan

F

rom 1924 onwards, a flurry of robot stories began to appear in Japan. These are sometimes referred to by academics as ‘Early Showa Robot Literature’. These stories came a decade after Japan’s victory over Russia in the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905), a war that halted Russia expansion in the Far East, taking most of the world, except Japan’s increasingly confident leaders, by surprise. It was the first time in modern history that a European power had been defeated by a country from Asia.

During this period, Japan was trying to find its ‘rightful’ place in the world, Japanese society was changing, and new technologies were emerging. This is when Naoki and others wrote their robot short stories in response to the times.

Following her defeat in the Second World War, Japan once again went through a period of introspection, figuring out its place in the world and what it meant to be a modern democratic nation during its occupation by Allied Forces, and then throughout the Cold War years.

All of which provided a rich narrative backdrop for Japan’s finest writers of science fiction and robot literature.

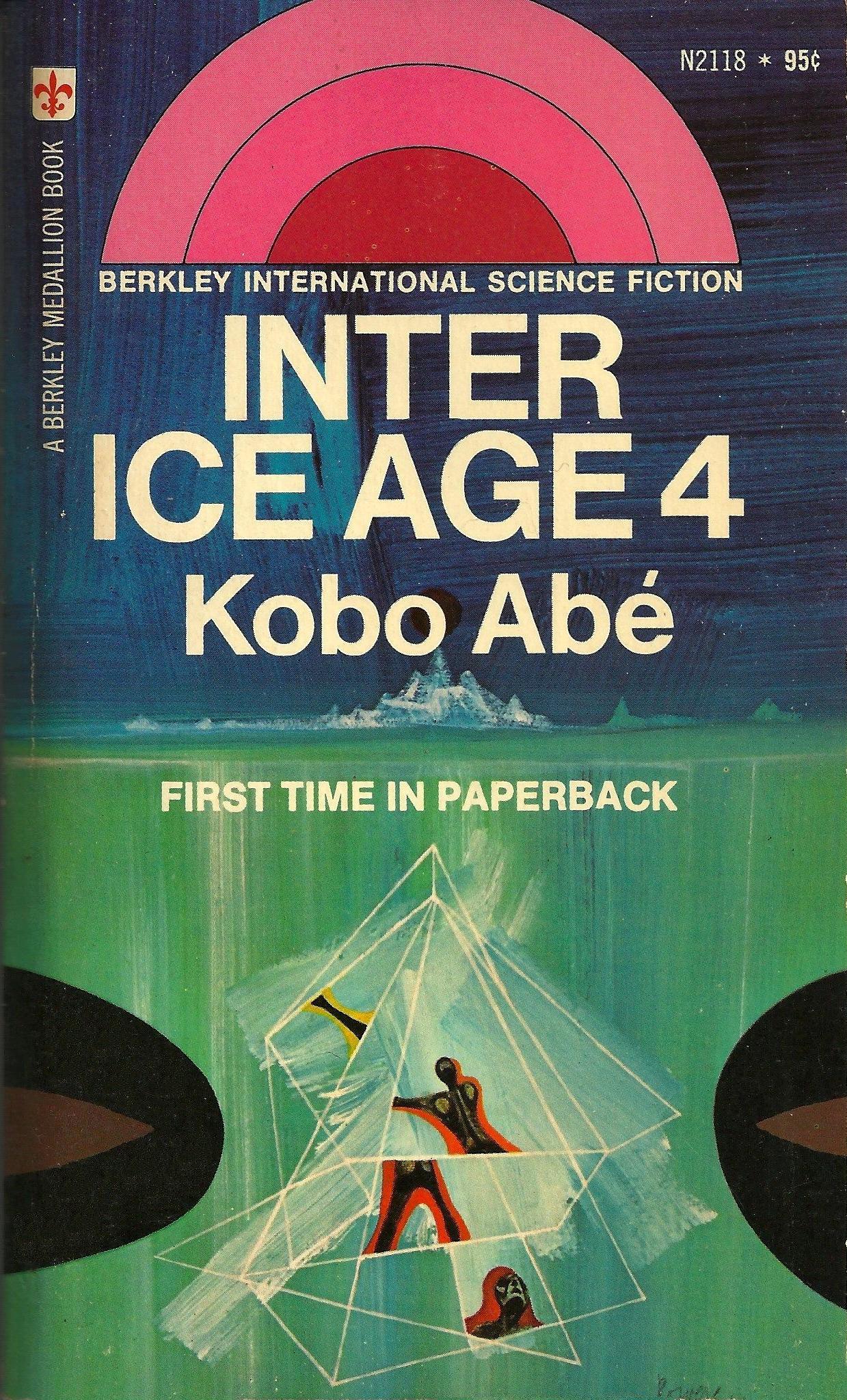

Cover of paperback edition of Inter Ice Age 4 by Kobo Abe (1924-1993)

Cover of paperback edition of Inter Ice Age 4 by Kobo Abe (1924-1993)It tells the story of a submerged world in the near future in which the polar ice caps have melted, leading to the creation (through genetic engineering) of an ‘aquatic human’ capable of breathing underwater.

In terms of its scale and sheer imagination, its impact on the science fiction genre in Japan was significant. Nevertheless, Abe is best known for his social commentary novel, The Woman in the Dunes, a jarringly dry novel about the futility and repetitiveness of modern Japanese existence.

Abe was himself no stranger to the world of science and science fiction. In the 1950s he had studied medicine at the University of Tokyo before becoming a writer and writing his series of enlightening stories about robots, mostly dealing with the theme of alienation within Japanese society.

The Allied occupation cast a shadow over post-war Japan. In 1951, Japan signed a peace treaty bringing an end to the occupation in 1952, allowing her to take control of rebuilding the country’s economy and infrastructure, as well as the development of the new technologies needed to make Japan’s industry internationally competitive.

This came at a social cost, as the benefits of the centralised planning took time to filter through to the men and women on the street. It continued to be a very difficult period creating a tremendous sense of dehumanisation for many. Abe’s robot narrative, R62 go no hatsumei, The Invention of R62, written in 1953, reflects this national mood.

It tells the tale of an engineer who loses his job after new technologies from an American firm are introduced at his workplace. Desperate about his predicament, he decides to kill himself. But before doing so, he is persuaded to enter into a financial arrangement with a university researcher who is trying to develop robots capable of replacing workers and making Japanese industry more efficient. As a last act he agrees to have his brain replaced with a controllable artificial one by the researcher.

The procedure is successful, but the consequences are unexpected and painful, especially for the engineer’s former employer. Abe’s other robot stories from the period including Eijyu undo, Perpetual Motion, have similar themes echoing the times.

By the 1960s, Japan’s economic miracle was starting to increase the country’s prosperity markedly. This was the decade in which the economy started to grow at 10% annually and Japan overtook West Germany as the world’s second largest economy. A consumer society was emerging, and the national narrative was changing. And inevitably, new robot narratives were coming to the fore.

One particularly interesting example was Bokko-chan, written in 1963 by Shinichi Hoshi (1926-1997), one of Japan’s best-known science fiction authors, who has an important literary award named after him. Bokko-chan was published the year before the first Tokyo Olympics, when Ian Fleming’s (1908-1964) novel You only Live Twice brings James Bond to Japan.

Bokko-chan is about a glamorous young female bar hostess, a type of Bond girl, with limited dialogue. And like all Bond girls, she too has an interesting sounding name: Bokko-chan. What nobody knows, of course, is that she is in fact a robot designed by the bar’s owner.

Bokko-chan helps increase the bar’s takings with her two simple but important functional abilities. Firstly, by making simple conversation and providing basic replies without expressing anything remotely like an opinion – often just repeating what she hears. And secondly, by her ability to drink copious amounts of alcohol, especially when offered to her by visitors that frequent the bar, where Bokko-chan sits at a dimly-lit counter.

Inevitably, one of the bar’s customers falls in love with this women of few words, which has terrible consequences, not just for him, but for the others drinking at the bar.

During the 1960s, Abe was very active. Aside from writing books that were social commentaries of the times, he also had a theatre troupe, which performed internationally including in New York. He wrote plays and wrote for television and radio, often with avant-garde themes. He also didn’t forget how useful robots could be as a narrative device. In the 60s he wrote a script for a television programme entitled Anata ga mo hitori, One More Like You.

One More Like You reflects the contrast of the previous decade when he wrote The Invention of R62 and Perpetual Motion. Austerity was now over and consumerism was gaining momentum. Set 50 years in the future, a wealthy woman decides to order a robot that is an identical copy of herself to conduct all the chores she doesn’t want to do. But she eventually discovers too late in the day that, in real life, you can’t have your cake and eat it.

-

- Robot Companions: New modern relationships

B

y 1965, almost half of Japan’s urban population was between the ages of 15 and 34 – and the number of men exceeded that of women in most major cities. Much was changing and it wasn’t all sex, drugs and rock-and-roll.  1960s Japanese student protests. Photograph: Hiroshi Hamada, Ikari to kanashimi no kiroku (A Record of Rage and Grief).

1960s Japanese student protests. Photograph: Hiroshi Hamada, Ikari to kanashimi no kiroku (A Record of Rage and Grief).Japan was a rapidly Westernising nation and many similar issues were coming to the surface in Japan. City-based youth with new values and attitudes wanted to express themselves and make themselves heard by the establishment.

Against this backdrop, Japan’s robot literature wasn’t entirely confined to the world of male authors. There were stories written by women too, though fewer in number. One example is the 1961 story by Yumiko Kurahashi (1935-2005) Artificial Beauty, Gosei bijo.

Kurahashi was a controversial author, also like Abe with an avant-garde bent, who often challenged gender and relationship norms. Artificial Beauty is set in the distant future when robots are sophisticated, genetically engineered, synthetic beings.

Controversial cover of 2014 New Year issue of The Japanese Society for Artificial Intelligence (JSAI) journal Jinkou Chinou, Artificial Intelligence. A public competition was used to select the cover, which was deemed sexist and led to a public apology from the journal’s editor. Image: space-hippo.net

Controversial cover of 2014 New Year issue of The Japanese Society for Artificial Intelligence (JSAI) journal Jinkou Chinou, Artificial Intelligence. A public competition was used to select the cover, which was deemed sexist and led to a public apology from the journal’s editor. Image: space-hippo.netInevitably and sadly Michiko’s husband and Eriko start spending more time together: he even starts using her as his secretary. This makes Michiko incredibly jealous. She hires a private investigator to find out what is going on, and then decides to kill Eriko – only to discover that Eriko is not a robot at all, but a human; while her husband is not just emotionally robotic at times, but actually a robot – one of the privileged artificial men that secretly control society.

A fact that is finally proven after Eriko’s death when he overcharges himself and self-destructs.

The story no doubt reflected how repressed many Japanese women may have felt at the time and the underlying gender inequality issues that were coming to the surface.

In the 1970s, the women’s liberation movement started to make its presence felt in several countries. Britain’s first national women’s liberation demonstration, for example, took place in March 1971 in London. Women carried placards demanding Equal Pay, Free Contraceptives & Abortions on Demand, and held up such items of oppression as aprons, stockings and shopping bags.

Japan had its own movement, uman ribu, which made many similar demands alongside local ones. Japanese women, however, got their movement going a year before British women, and held their first demonstration in October 1970.

Many of these Japanese women demonstrating were reportedly furious over the way the Japanese student protest movement between 1967 and 1969, which had caused riots and deaths, had treated female students. Not only had female students been denied an equal role, but some women had been forced into having abortions following ‘experimenting’ with ‘free love’ with radical male students, after the demonstrations were over.

-

- Women’s Lib, the Pill and Unexpected Robotic Consequences

L

ike American and British women, Japanese women also campaigned for abortion rights and access to the contraceptive pill. But it wasn’t until 1966, six years after its approval in the United States, that a high-dose pill was approved in Japan. And even then, it was restricted to those with medical conditions; and Japanese women were reliant in most instances on male doctors for prescriptions. In contrast, birth control was made legal in the United States for all, irrespective of marital status, in 1972, and a low-dose contraceptive pill became available in 1980. Not all Japanese men were comfortable with uman ribu. What might the long-term repercussions be for men, and how might their lives change? Some men who harboured such concerns would label women who were part of the movement as ‘unattractive’ and ‘hysterical’.

This was the perfect background for the brilliant madcap surrealist and famed science fiction author, Yasutaka Tsutsui, who has an uncanny knack of imagining things that actually come to pass.

The timing of some of his stories is also interesting as their publication came hard on the heels of an important international conference on women held in Mexico City in 1975. The first United Nations World Conference on Women, which coincided with the International Women’s Year, was designed to remind the international community that discrimination against women continued to be a persistent problem in much of the world. Tsutsui’s stories were written to remind readers of something altogether different.

The first story, Narcissism, starts by listing Asimov’s famous Three Laws of Robotics, a set of rules devised by the science fiction author Isaac Asimov (1920-1992). These being: 1 – a robot may not harm humanity, or, by inaction, allow humanity to come to harm; 2 – a robot must obey orders given to it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law; and 3 – a robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

Narcissism is the tale of a man who buys a second-hand hybrid robot that combines the functionality of a sex robot with a housekeeper robot.

Tsutsui creates a world in which male demand for female androids is so great that men who crave real women are few and far between – making them highly desirable. Nevertheless, our protagonist ultimately succumbs to market trends when the second-hand android market begins to take off.

Interestingly, in this future world there are no robots designed for women’s needs or desires, and all the regulators and manufacturers are men. For servicing men, however, almost every type of robot you could possibly imagine has been developed.

This might not seem like a very credible future scenario, particularly when you take into account the growth of the women’s liberation movement at the time. But then again, one can consider the ridiculously long approval process for the low-dose contraceptive pill in Japan, which took decades to be approved in 1999, despite its approval in the United Sates much earlier. Viagra, on the other hand, took just six-months.

In the story, our protagonist eventually buys his android who looks ‘utterly incredible’ and non-robot like. However, she is not what her new owner expected or had hoped for, since she wants to be treated as a humanoid, not as an order-obeying robot, and wants to be called Mari. In short, she is too lifelike, and too much like a real woman. She even wants to be told that she is loved and is beautiful.

The owner phones the salesman the next day from his office to complain that he has been sold a ‘narcissistic robot’. The reader is left wondering if Mari is in fact a ‘jilted woman’ pretending to be an android, and looking for a stable, long-term relationship, But unlike Kurahashi’s story from the 60s, this tale finally reveals that Mari is not human. And the reader will come to understand the relevance of Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics, and why Mari has been looking for a new ‘owner’.

English-language collection of short stories by Yasutaka Tsutsui, published in 2017. Narcissism and Sadism are both included in the collection.

English-language collection of short stories by Yasutaka Tsutsui, published in 2017. Narcissism and Sadism are both included in the collection.Her lawyer has ‘discovered’ that the factory is making and selling an advanced android that looks just like her – thereby infringing her intellectual property (IP) rights. In this bizarre story that explores themes of vanity and identity, the manager finally decides on taking a high-risk strategy and introduces the actress to R5-13M 1095, the model in question, in order to let the consequences dictate the solution.

As they wait for R5-13M 1095 to arrive, a discussion ensues. The celebrity wants to know why demand for androids is increasing, and is furious when the manager suggests that it might be because women have become too domineering and demanding. And that men have become sick of having to deal with the stress created by both their emotional and material needs.

Interestingly, Japanese fertility rates have fallen, as Tsutsui seemed to predict in the 1970s. According to surveys, one third of Japanese men between the ages of 16 and 19 have lost interest in physical relationships, with many saying they now prefer virtual girlfriends, as you don’t need to marry them. A company called Gatebox has even launched a virtual wife service.

In the story our celebrity eventually gets to meet her doppelganger who is identical in appearance to the actress, who isn’t very self-aware. But our protagonist is shocked by the android’s aggressive and hysterical attitude, and complete lack of class. So she becomes convinced that she now has to license her IP to the company to allow them to make a model that is closer to her ‘real’ self. Inevitably, the story ends up with a twisted and tragic case of mistaken identity.

-

- Did Japan’s post-war Robot Literature predict the Nation’s Future?

F

ollowing trends and attitudes to their extremes and pushing narratives firmly to their logical conclusions, no matter how uncomfortable or awkward, is something that the best Japanese authors seem to do brilliantly and very entertainingly. There can be little doubt that science fiction can influence future events: encouraging them to happen more quickly; or by ensuring that certain scenarios stay within the pages of books. Naturally, only the best stories that resonate with the times or strike a national cord create a legacy.

Singing robots, Seasons, with bellows that send air to artificial vocal chords designed by Maywa Denki. On display as part of the ‘Nonsense Machines’ exhibition at the Nagasaki Prefecture Art Museum. Photo: Red Circle Authors Limited

Singing robots, Seasons, with bellows that send air to artificial vocal chords designed by Maywa Denki. On display as part of the ‘Nonsense Machines’ exhibition at the Nagasaki Prefecture Art Museum. Photo: Red Circle Authors LimitedOne might expect 50 years to be long enough for some narrative fiction to have become a reality, especially as authors often set their stories 50 years in the future. Conversely, reading today’s robot stories may give us an inkling into to what life might be like living in a Robot Superpower 50 years from now.

Today Japan does actually boast robot restaurants and cafes. And while there are no fully functioning blue robot cats currently on the market, you can buy a robot dog: the AIBO has been developed by Sony and is now in its second generation. Rather more spookily, the Japanese author – Soseki Natsume (1867-1916) – has been brought back from the dead in robot form. And robots like Toyota’s Kiribo, which looks like Japan’s favourite fictional robot, Astro Boy, and the Japanese space drone Int-ball, have been sent into space.

While human brains haven’t yet been replaced with robot brains to create industrial robots, most Japanese factories and warehouses are now heavily automated and use robots.

In fact, four of the world’s six largest industrial robot makers are Japanese. Lifelike androids and sex dolls are now more realistic than ever before. In terms of everyday, practical use, robots have been designed to vacuum, cut the grass and do the laundry. And companion robots are also becoming increasingly popular for accompanying and entertaining both the young and the elderly.

Robots provide authors with a brilliantly rich vein of inventive literary avenues to explore, ranging from the comic and absurd to the downright menacing and tragic.

They can be used to question many of the fundamental issues in our lives: our attitudes to gender; beauty; our bodies, our parents as well as the boundaries of society itself, be it in Japan or elsewhere.

Robot literature at its very best can even help us understand ourselves better. Now that really is uncanny.

© Red Circle Authors Limited

Nathalie Kosciusko-Morizet (Wikimedia) Olivier Ezratty

Déplacement au Japon en février 2009.

Nathalie Kosciusko-Morizet (Wikimedia) Olivier Ezratty

Déplacement au Japon en février 2009.