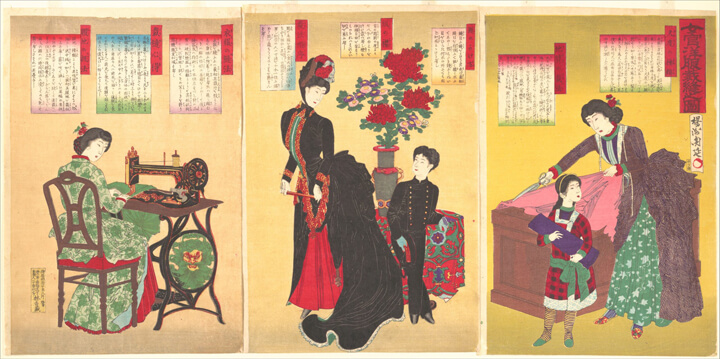

Japanese court ladies sewing western clothing and the Empress (centre), wearing a close-fitting, French-style mantelet, accompanied by the prince, sporting his school uniform. In Meiji period (1868-1912) Japan noble ladies were encouraged, with the Empress leading the way, to wear elegant western dress on official occasions to prove to international visitors that Japan was an equal to any of the world’s leading modern nations. Woodblock print, August 23rd, 1887 by Yoshu Chikanobu (1838–1912). Image Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gift of Lincoln Kirstein, 1959.

Japanese court ladies sewing western clothing and the Empress (centre), wearing a close-fitting, French-style mantelet, accompanied by the prince, sporting his school uniform. In Meiji period (1868-1912) Japan noble ladies were encouraged, with the Empress leading the way, to wear elegant western dress on official occasions to prove to international visitors that Japan was an equal to any of the world’s leading modern nations. Woodblock print, August 23rd, 1887 by Yoshu Chikanobu (1838–1912). Image Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gift of Lincoln Kirstein, 1959.This elusive power is thought to make one immortal as its effects ripple through time and space, and the one essential quality for possessing it, according to experts, is authenticity.

Influence can, however, also be delusional, manufactured, imagined or even brilliantly conjured up through the pages of a book or on the screens of our phones.

In our social medial age the words influence and influencer are now mostly used as terms for shaping audience attitudes; usually through public perceptions of personality, conduct, character and style; often of the most excruciating attention-grabbing type.

In an age replete with incredibly short attention spans, this is something that comedians, models and actors and actresses with millions of followers strive and struggle to achieve, or simply maintain.

The media in Japan now obsessively tracks those who are commanding the rankings and can be deemed, for example, the top 10 and top 20 Japanese influencers. Whether these moments of fame and influence will be fleeting, lasting only one or two software evolutions and upgrades, is anyone’s guess.

There is, however, precedents: two enduring fictional characters with strongly marked personalities that arrived on Japan’s shores from Britain in the space of two years – 1894 and 1895 – in the pages of books, and subsequently in every form of new media “up-grade” that has followed in the wake of the printed page.

They have shaped Japanese audiences and their attitudes over many aspects of life including how to dress, how to think, and observe the world around them. And their influence continues to this day.

Their arrival in Japan in translation was at a time when The Land of the Rising Sun was opening up to the West, modernising, and expanding its ambitions during the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895). During this period, Japan forced Korea’s markets open, and as a result, China had to initially recognise Korea’s independence, Korea was an important ‘client state’ of China’s at that time. Japan also drove China to cede control of Taiwan and other territories. These historical events link both of our fictional characters in terms of their Japanese debuts in the Japanese language.

However, their actual inceptions were, in fact, more than two decades apart, in 1865 and 1887 respectively. On the surface, both are inquisitively independent and determined individuals, but here the similarities end. They are actually poles apart; one being a violin playing middle-aged man with a close male friend; and the other a pinafore-wearing seven- year-old girl, whose most important acquaintance is a talking rabbit.

Nonetheless, they have both left an enormous creative and cultural legacy, spawning thousands of imitations and adaptations, and have undoubtedly shaped the attitudes of many in Japan – from the rich and famous to the ordinary man on the street. And on a scale that even today’s influencers would find inconceivable.

-

- Eccentric and Virtuous

The seven-year-old girl named Alice arrived one year later with the first Japanese translation of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll (1832-1898).

Alice’s debut was in a Japanese magazine, Shonen Sekai (A Boy’s World), in serial form in 1895, and followed by a second appearance in 1899 in another magazine Shojo Sekai (Girl’s World).

Alice by John Tenniel (1820-1914), 1865. Image: Wikipedia

Alice by John Tenniel (1820-1914), 1865. Image: WikipediaAccording to Japan’s National Diet Library, the first full and complete translation, in book format, in which the whole story of the original Alice was translated faithfully, was published in 1910 with a protagonist called Ai-Chan.

This edition, translated by Eikan Maruyama and published by Nagai Shuppan Kyokai, also contains copies of John Tenniel’s (1820-1914) celebrated original illustrations depicting Alice in her knee-length puffed sleeve dress and her pinafore and practical ankle-strap shoes, which arguably have been as influential as the story itself in Japan.

Holmes fans had to wait until 1955 for the full-Sherlock. When all of the Holmes stories were finally translated into Japanese by Ken Nobuhara (1892-1977).

-

- The Creative Fog of Translating Personality

The difficulty of rendering the Alice books into Japanese and the freedom of the early translations has helped inspire many to try to create the perfect translation or a brilliant creative adaptation or homage to either or both of the Alice books.

This enticing rabbit hole of a challenge has compelled many of Japan’s most renowned and important authors like Ryunosuke Akutagawa (1892-1927) and Yukio Mishima (1925-1970) to take the leap.

Sherlock Holmes has also seen countless creative adaptations. And despite not being the first fictional foreign detective to arrive on Japan’s shores, he continues to inspire, be reimagined, reinvented and rewritten. Indeed, he is regarded by many, including the Japan Sherlock Holmes Club, to be the most famous Englishman in Japan.

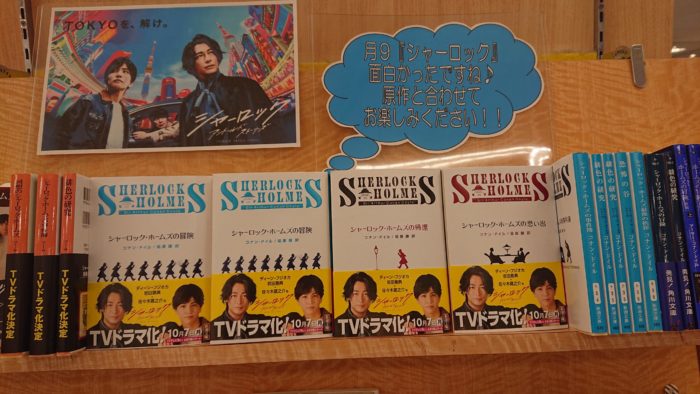

Books based on a TV series linked Japanese adaption of Sherlock Holmes on sale in Tokyo. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited

Books based on a TV series linked Japanese adaption of Sherlock Holmes on sale in Tokyo. Photograph: Red Circle Authors LimitedBut there is something seemingly special about this conulting sleuth’s presence in Japan. Surveys of school libraries in Japan of the top five books read or requested often include a Sherlock Holmes titles in some form. And booksellers and librarians, who often came across Holmes for the first time in primary school in various adaptations including comic book form, cite his endearing, super-intelligent and honourable personality as the reasons why he is still one of Japan’s favourite literary characters.

Authors like the mystery writer Soji Shimada also point out that another important factor in his popularity is the quality of the stories and the writing. Books featuring Holmes in all his myriad Japanese forms have sold in the tens of millions in Japan.

Nonetheless, many of the world’s most influential books, which boast international reach, impact and influence amongst decision-makers and world leaders, are often books that haven’t actually been read, and this may also apply in Japan to both Alice in Wonderland and Sherlock Holmes.

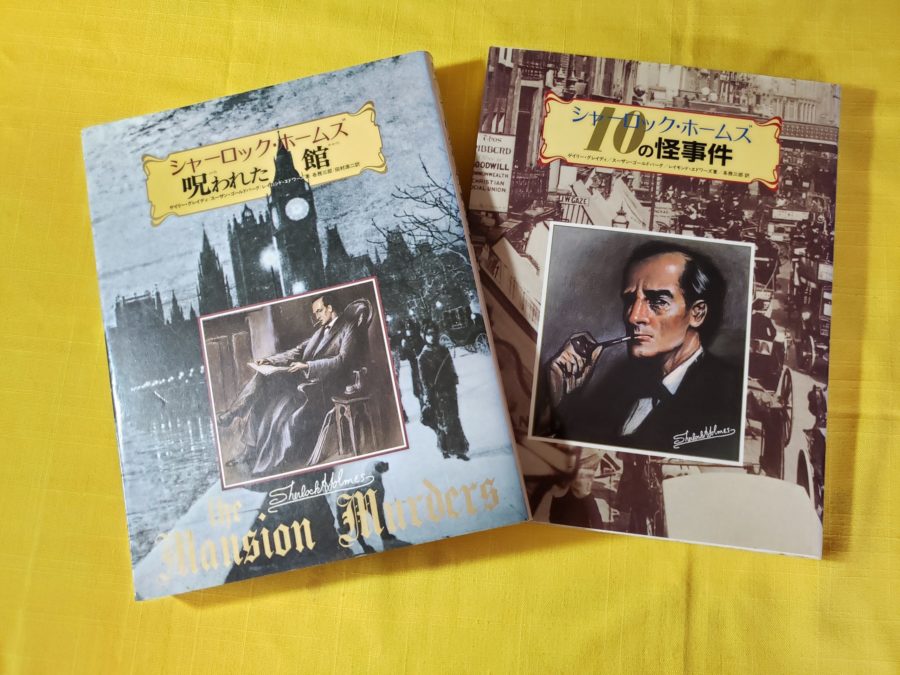

Japanese language editions of Sherlock Holmes books, pastiche detective games books. Photograph: Hiroshi Minemura.

Japanese language editions of Sherlock Holmes books, pastiche detective games books. Photograph: Hiroshi Minemura.The Japanese literary critic and writer, Yasunari Sadao (1885-1924), for instance, adapted The Man with the Twisted Lip in 1912 in his work The Stone Lantern, Kasuga Doro, after coming across the famed English detective in The Jewish Lamp, a 1907 adaptation by Maurice Leblanc (1864-1941) in which Holmes, the gentleman detective, confronts Leblanc’s gentleman thief Arsene Lupin.

Others such as the popular contemporary mystery and crime writer Mizuki Tsujimura, for instance, first encountered Sherlock Holmes as a child, but only really “met” the detective in the BBC series Sherlock starring Benedict Cumberbatch, which inspired her to read the full editions in translation for the first time.

In this regard she is in very good company as some of Japan’s most influential authors such as Junichiro Tanizaki (1886-1965) and Ryunosuke Akutagawa have read and analysed Conan Doyle’s prose and adapted him or filleted him as only a highly skilled fan can do.

This type of creative blurring and “fan fiction” has been accentuated by multiple film adaptations. This also applies to Alice, who many in Japan have come across through the 1951 animated musical Disney adaptation and not the actual Alice books: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass, and What Alice Found There.

-

- Curiouser and Curiouser

Nonetheless, the detective had a strange type of duality of being the protagonist of popular mass-market novels and also a tool for education, sometimes for Japan’s elite.

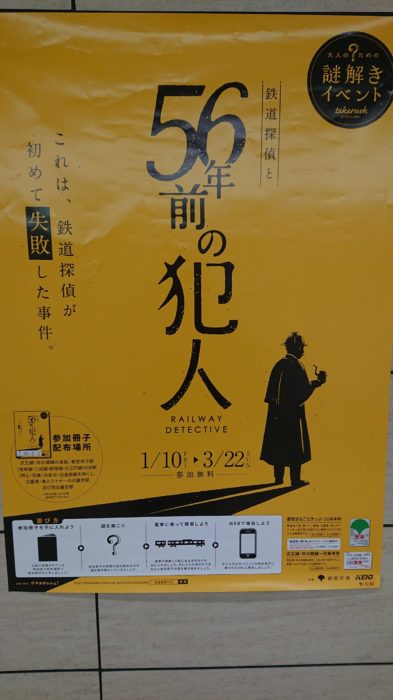

Promotional poster at a Tokyo subway station with a Sherlock Holmes icon. Photograph: Red Circle Authors Limited

Promotional poster at a Tokyo subway station with a Sherlock Holmes icon. Photograph: Red Circle Authors LimitedIn a similar fashion to how a certain type of English schoolboy might study Lucretius (99BC-55BC), the Roman poet and philosopher, and his poem On The Nature of Things – and commit to memory such lines as: “to none is life given in freehold; to all on lease” and “some nations increase, others diminish, and in a short space the generations of living creatures are changed and like runners pass on the torch of life”.

Japan’s police force and its aspiring detectives probably first read about Holmes in the pages of their professional journals and newspapers as opposed to the original English versions or faithful translations. He was introduced in the early 1900s as a role model and educational device for training Japan’s law enforcers on how real detectives should go about their work with professional competence, using a combination of logic and scientific reasoning.

However, not all readers have stuck to these derivative forms. Some in Japan haven’t only been interested in seeing Holmes through the eyes of his many interpreters but to observe him as he was originally conceived; a sentiment that Holmes himself would have no doubt approved of.

Such individuals have famously included aristocrats like Count Makino Shinken (1861-1946), the Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida (1878-1967), and a Vice Minister of Finance, Kohki Naganuma (1906-1977), to name just a few important individuals who tried to shape modern Japan, protect the nation’s independence, and decided that reading the original English editions was, shall we say, elementary, and required reading.

Many others who, like Tsujimura, came across Holmes for the first time in adapted Japanese language digests in their primary school libraries, have been inspired to study English so that they can enjoy the original tales first hand.

Some have gone on to become lifelong fans; graduating from Japanese children’s editions, to full editions in Japanese, and then to the full-Sherlock in English.

Bookshelf and pictures, the Holmes Corner, at the Tokyo home of Hiroshi Minemura, a senior publishing executive at a major international publisher who as a child was determined to learn and master English with the aim of reading the original Sherlock Holmes tales, he enjoyed reading so much in Japanese, in English. A decision that changed his life and took him on his own international publishing adventure. Photograph: Hiroshi Minemura

Bookshelf and pictures, the Holmes Corner, at the Tokyo home of Hiroshi Minemura, a senior publishing executive at a major international publisher who as a child was determined to learn and master English with the aim of reading the original Sherlock Holmes tales, he enjoyed reading so much in Japanese, in English. A decision that changed his life and took him on his own international publishing adventure. Photograph: Hiroshi Minemura

-

- Tweedledee and Tweedledum: Logic, Nonsense and Values

Promotional sign at a Japanese shop in Tokyo which specialises in selling school uniforms showing that some Japanese school uniforms have changed very little since the 1880s. See central panel top image .Photograph: Red Circle Authors

Promotional sign at a Japanese shop in Tokyo which specialises in selling school uniforms showing that some Japanese school uniforms have changed very little since the 1880s. See central panel top image .Photograph: Red Circle AuthorsEven though Western hairstyles were becoming increasingly common in Japan, dress codes were still in flux and many weren’t sure how to dress themselves, let alone their children and young girls who were starting to go to school in increasing numbers.

Modern, wealthy kimono wearing men sometimes wore western-style hats, carried western-style umbrellas and those who could afford them liked to show off their pocket watches.

Much was changing. Japan was in the early phase of developing a nationwide railway system after the first railway line between Tokyo and Yokohama had been opened in 1872. The nation was urbanising and modernising rapidly, and there were also huge changes being made to the way the nation educated its youth. The torch of modernity had come to illuminate Japan and the nation was hardly diminishing; it was in an astonishingly expansive mode.

In 1890 only 31% of girls, for example, completed primary-level education but this rose to 72% by 1900, the year when school uniforms for secondary school female students were introduced.

School girl wearing Heian Jogakuin (St. Agnes’) school uniform.

School girl wearing Heian Jogakuin (St. Agnes’) school uniform.Some say this uniform is based on or at least reminiscent of Alice’s practical style of attire portrayed in Tenniel’s illustrations, even if these very first uniforms were actually modeled on a British Navy uniform.

Translating these two quirky characters into Japanese with their unusual dialogues and narratives, which can at times be nonsensical even for native English readers, wasn’t easy, but the protagonists had a major impact on Meiji period Japan (1868-1912) with these two fictional characters holding up sensational mirrors on apparent Western-ways.

Holmes was considered the personification of essential Western values, a virtuous individual, and an excellent role model. And Alice was thought to represent the ideal way a polite young girl should dress, behave and explore her environment while making sense of an emerging world that could at times be highly perplexing and nonsensical.

School Uniforms on sale in a Japanese department store. Photogragh: Red Circle Authors Limited

School Uniforms on sale in a Japanese department store. Photogragh: Red Circle Authors Limited-

- Managing the Impossible

Japan had in a sense been socially conditioned by the long and peaceful Edo period (1603-1868) with its rigid hierarchies and Shogun-run state apparatus. These cultural and state institutions were in decay or at least in flux and Japan now found itself on the cusp of a feverish new era.

The Meiji Emperor (1852-1912), the figurehead of these new times, had announced that he and his family would begin eating beef and mutton. This was something that until then had been taboo and not part of Japanese establishment etiquette.

Western cookbooks and etiquette books were being published; new sports such as rugby, baseball and tennis were being played; and Japan was shifting from a country-focused inwards to an international power in its lead up to the Russo –Japanese War (1904-1905). A war in which Japan was the victor.

Some believe that this period, with its struggles and the challenge of fusing long-held traditions with modernity and conflicting imported new concepts, has shaped contemporary Japanese attitudes, inclinations and psychology more than any other period in Japanese history. More so than even Japan’s post-war occupation by Allied Forces.

Learning, coping with, and dreaming about the extraordinary adventure of modern life was for most ordinary Japanese people somewhat like Alice’s own adventures in Wonderland. It had become an essential life-skill.

Alice and Holmes, who both in their own ways pursue order and understanding, provided a lesson on how to deal with the impossible. And perhaps this goes some way in explaining their popularity.

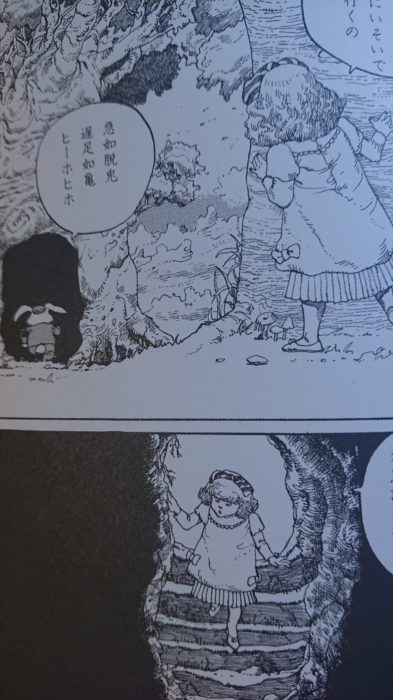

Photo of a panel from Katsuhiro Otomo’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland showing Alice worrying about how narrow her subterranean route is becoming.

Photo of a panel from Katsuhiro Otomo’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland showing Alice worrying about how narrow her subterranean route is becoming.“Alice laughed: “There’s no use trying,” she said; “one can’t believe impossible things.” “I daresay you haven’t had much practice,” said the Queen. “When I was younger, I always did it for half an hour a day. Why, sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.”

They are both now integral parts of Japanese culture even if the meaning and narratives of both Alice and Sherlock have morphed and been reshaped into different unique local forms and formats.

Kusama references Alice in her work and identifies with her personally and has created illustrations for a special edition of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, which has been described by critics as the perfect pairing.

-

- Mirror Memory: Victorian Fiction through the Looking Glass

Japanese cabinet (The Adventures of the Gloria Scott), Japanese armour (The Adventures of the Greek Interpreter), baritsu (The Adventures of the Empty House), the Emperor Shomu and his association with the temple Shoso-in near Nara (The Adventures of the Illustrious Client) and the Japanese vase (The Adventures of the Three Gables).

Photo of panels from Katsuhiro Otomo’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland showing Alice observing and following a Mao-suited white rabbit into a subterranean domain.

Photo of panels from Katsuhiro Otomo’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland showing Alice observing and following a Mao-suited white rabbit into a subterranean domain.Alice who some argue embodies the perfect young girl of the Meiji period, has shape-shifted effortlessly into a symbol of contemporary female freedom and adventure. She can seemingly be reinvented again and again in manga, anime and film for each new generation.

An excellent example of this is the 1980 Alice adaptation by Katsuhiro Otomo, best known for his 1988 post-apocalyptic animation Akira. His superb adaptation has helped to encourage many of Japan’s most creative artists to plunge down a similar creative passage of adaptation and interpretation for manga readers.

Otomo’s version contains a Mao-suited white rabbit and clever use of illustration size and graphic panels to depict the shrinking or enlarging promotions of the worlds Alice descends into as she leaves our physical reality.

But where did Sherlock Holmes disappear to between his apparent death after his fall at Reichenbach Falls in The Final Problem and his dramatic reappearance three years later at 221B Baker Street, with a flask in his hand, in The Adventure of the Empty House?

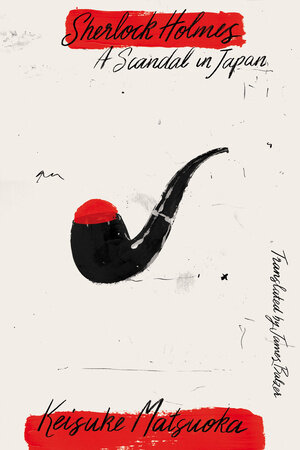

Japan of course, according to Sherlock Holmes: A Scandal in Japan by Keisuke Matsuoka. An adventure that involves the Japanese Prime Minister Hirobumi Ito (1841-1909) and the English detective trying to acclimatise to 19th century Japan in a very special case, published in Japanese in 2017 and in English in 2019.

Cover of English translation of Keisuke Matsuoka’s Sherlock Holmes: A Scandal in Japan translated by James Balzer.

Cover of English translation of Keisuke Matsuoka’s Sherlock Holmes: A Scandal in Japan translated by James Balzer.-

- British Immortals?

The reasons for this, like the number of adaptations they have inspired, are myriad but perhaps it is best to leave the final word to another British author, who also penned a tale about a rabbit and had the foresight to know how to protect where she lived for future generations. The area in question was the Lake District, and she ensured an important physical as well as literary legacy. Her name was Beatrix Potter (1866-1943).

And as Potter famously said: “I hold that a strongly marked personality can influence descendants for generations.”

Pipe collection in a special handmade Japanese-style case belonging to a Japanese Sherlock Holmes fan, Hiroshi Minemura. A senior publishing executive at a major international publisher who as a child was determined to learn and master English with the aim of reading the original Sherlock Holmes tales, he enjoyed reading so much in Japanese, in English. A decision that changed his life and took him on his own international publishing adventures in London, San Francisco, Brussels and Amsterdam. Photograph: Hiroshi Minemura

Pipe collection in a special handmade Japanese-style case belonging to a Japanese Sherlock Holmes fan, Hiroshi Minemura. A senior publishing executive at a major international publisher who as a child was determined to learn and master English with the aim of reading the original Sherlock Holmes tales, he enjoyed reading so much in Japanese, in English. A decision that changed his life and took him on his own international publishing adventures in London, San Francisco, Brussels and Amsterdam. Photograph: Hiroshi Minemura